SAEDNEWS: Join Saed News as we explore the traditions of Mehrgan, cherished by Zoroastrian followers.

In ancient Iran, a festival was held every month, precisely when the name of the day matched the name of the month. Each month had its own name, and each day within the month also had a unique designation. Mehrgan is one of the most important ancient Iranian celebrations that has survived through the ages and is still observed in some parts of Iran today. Mehrgan is a Zoroastrian and Iranian autumnal festival, celebrated in the fall, and in modern Iran, it is marked on the sixteenth day of Mehr in the Persian calendar.

Mehrgan is dedicated to the ancient Iranian Zoroastrian deity Mithra (Mehr in Persian). Also known as the Mitrakana festival, it was the second most significant festival for ancient Iranians after Nowruz, often considered the beginning of the Hellenic Persian New Year. Historically, the festival was celebrated at the start of the month of Mehr, but today it spans from the 10th to the 16th of Mehr. Mithra, revered as the god of friendship, love, and affection, was highly respected. Beyond Zoroastrianism, Mehrgan is also recognized as a traditional autumnal harvest festival. Its origins date back to pre-Islamic times, making it one of the few ancient festivals still celebrated by the general public in contemporary Iran. Mehrgan occurs 195 days after Nowruz.

Many stories surround Mehrgan. Some say it commemorates the victory of Kaveh and Fereydun over Zahhak, imprisoning him in Mount Damavand. Others claim it marks the day God brought light to a darkened world, or the creation of Mashy and Mashyaneh (Adam and Eve), or even the birth of the sun. Broadly, Zoroastrian texts divide the Iranian year into two equal seasons: summer and winter. The transitions are celebrated through Nowruz (spring equinox) and Mehrgan (autumn equinox). Farmers harvest their crops on these days and offer prayers of gratitude, making Mehrgan a festival of thanksgiving as well.

The word Mehr appears in Avestan as Miora, in Old Persian and Sanskrit as Mitra, and in Pahlavi as Mitr. Today in Persian, it is Mehr. While it may seem confusing, Mehr represents a god, an angel, the sun, and the seventh month of the Iranian calendar. When Indo-Europeans lived together, Mithra was among their principal deities. During the Achaemenid era, Mithra’s name frequently appeared on stone carvings. The Achaemenid army bore a banner depicting Mithra in the sunlight. In Persepolis, Mehrgan was celebrated in a grand manner—marking both the harvest and tax collection. Visitors from across the empire brought gifts for the king, creating a festive atmosphere of excitement and joy.

The festival was a spectacle: people from different regions arrived on horseback with gifts, heading toward the royal palace. Ancient Iranians regarded Mithra as the god of love, friendship, covenants, and light, later symbolizing the sun. Soldiers revered him, singing hymns in his honor. As the Achaemenid Empire expanded, Mithra worship spread to other lands. Many Roman emperors adopted Mithraism; Julian the Apostate became a devoted follower and planned to visit Mithra’s homeland in Iran but was killed en route. Legends say he offered his blood to the sun as a final gift. Many Mithraic traditions and prayers survive today, some incorporated into Christianity, such as the observance of Sunday—the day dedicated to the sun.

Mehrgan is the second most important Iranian festival after Nowruz, with a history exceeding 3,000 years. Although its roots predate Zoroastrianism, the festival became a major Zoroastrian celebration afterward. Scholars suggest Mehrgan aligns with the autumn equinox (the first day of the seventh month, Mehr), yet it is commonly celebrated on the sixteenth day of Mehr in the Zoroastrian religious calendar. The festival lasts six days, beginning with the “Mehr Day” and concluding on the twenty-first day, called “Ram Day.” The first day is “Small Mehrgan,” and the last is “Great Mehrgan.”

Before Zoroastrianism, Iranians worshipped multiple gods, among which Mithra was key. When Darius rose to power, he respected these older beliefs rather than replacing them, blending Zoroastrianism with the ancient polytheistic faiths. Portions of the Avesta are dedicated to Mithra. Mitrakana, the greatest Achaemenid festival, honored Mithra and marked the beginning of the Hellenic Persian New Year on the first day of Mehr, known as Bagayadi (meaning “remembrance of God”). Today, farmers in some regions still regard it as the start of the agricultural year.

The festival was observed at the start of Mehr because, in the Achaemenid era, the new year began with the autumn harvest. Agricultural life was closely tied to seasonal cycles, with the farming year starting in autumn and ending at summer’s close. This tradition continues among modern Iranian farmers, who hold various local festivals to celebrate Mehrgan and the harvest season.

Clothing: From the Achaemenid to Parthian periods, Iranians wore purple garments on the first day of Mehr, accompanied by celebratory messages—similar to today’s greeting cards—placed on the ceremonial table.

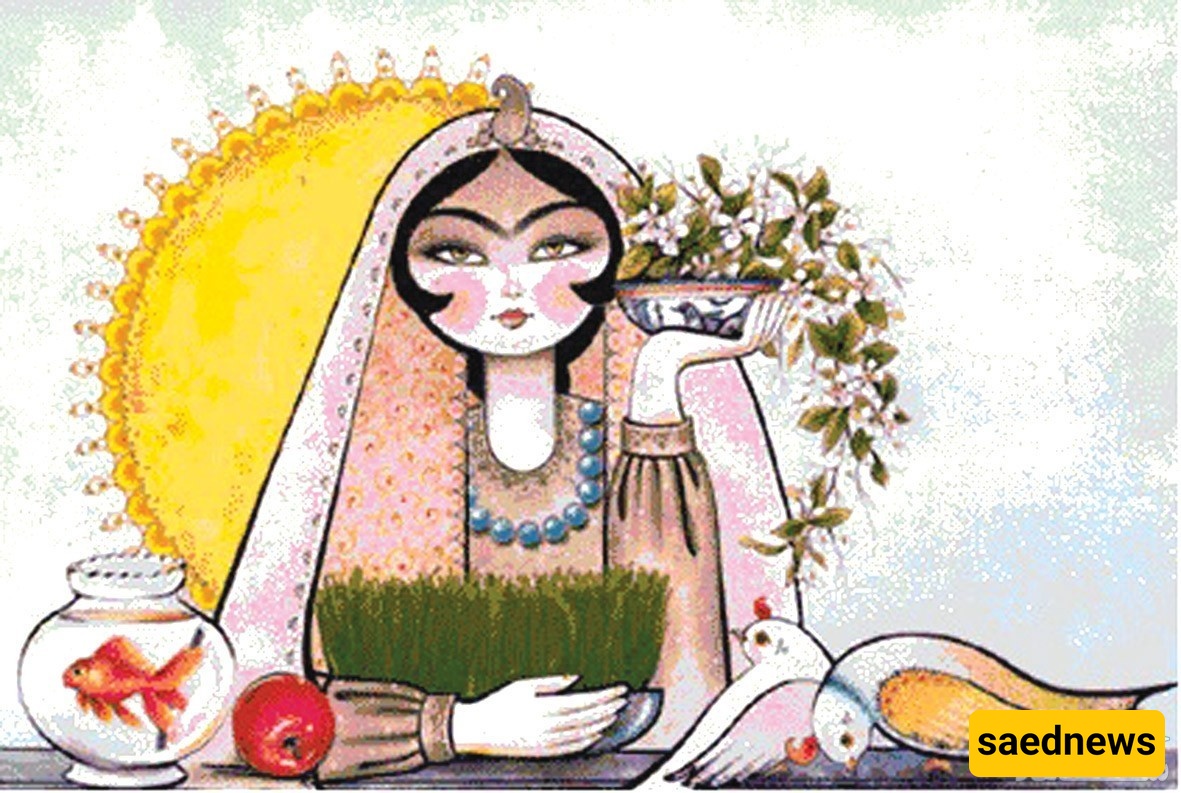

Mehrgan Table (Sofreh): Like ancient Nowruz, a special table was arranged with mirrors, bowls of rosewater, and symbolic items such as nuts, raisins, vinegar, thyme, violets, basil, kohl, incense, and “esfand” seeds. Autumn fruits, including pomegranates, grapes, apples, figs, almonds, and quince, were displayed. Local delicacies, special bread made from seven grains, and traditional drinks also featured.

Music and Poetry: Songs celebrating Mehr and Mithra were performed. While details of the ancient Mehrgan music are scarce, the Kitab al-Musiqi al-Kabir by Al-Farabi mentions a Mehrgan mode, and Nizami Ganjavi’s Khosrow and Shirin includes a musical mode named “Mehrgani.” Prominent Iranian musicians have incorporated these melodies into traditional music.

Opening Ceremony: Guests sprinkled rosewater on their hands and faces, gazed into mirrors, and took symbolic bites of sweets. They danced in groups to music, sang hymns, and burned fragrant herbs like esfand and amber in ceremonial flames, celebrating both the agricultural and personal new year with joy.

Closing Ceremony: People joined hands around blazing fires, concluding the festival with unity and celebration.

Poetic Reflections: Mehrgan is referenced in the works of poets such as Ferdowsi, Rudaki, Farrokhi, Daqiqi, Ansari, Nasir Khusraw, and Manuchehri, offering valuable insights into the festival’s historical and cultural significance.

Festivals are rooted in a country’s history and culture, forming an essential part of its intangible heritage. Celebrating them preserves ancestral traditions and conveys the stories of past generations to future ones. Today, Mehrgan is celebrated in only a few Iranian cities. To safeguard this invaluable legacy, it should be observed with the grandeur and attention to ritual that it deserves.