SAEDNEWS: Chega Sofla ancient site in Dasht-e Zohreh, southeast of Khuzestan province, is one of the most key civilizational links of Persian Gulf, where the world’s first brick tomb, an elaborate shrine, and unique evidence of the privileged position of women in the 5th millennium BC have been discovered.

Abbas Moghaddam, archaeologist and head of the Chega Sofla excavation team, told Miras Aria (CHTN) that the site of Chega Sofla was first identified in 1971 during a short-term survey by German archaeologists in Behbahan County. Since then, it has been recognized as one of the Persian Gulf’s most significant civilizational sites.

“Despite several excavation seasons, we have not yet reached the pristine layers of this historical site,” Moghaddam said. “However, the current findings indicate an age as early as the early 5th millennium BC.”

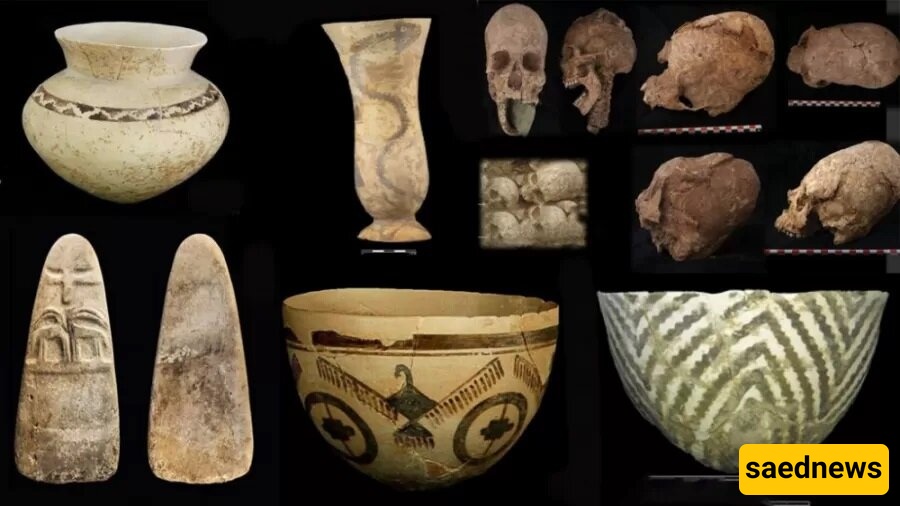

He described the most remarkable discoveries as the unique tomb architecture of Chega Sofla: “The tombs here are truly eternal homes, masterful architectural structures built with brick. Their precise proportions and engineered design provide a serious lesson in ancient funerary architecture.”

Moghaddam noted that the world’s first brick tomb, discovered at this site, is among the most important evidence of funerary architecture in southwestern Iran and across the Persian Gulf region.

Discussing the habitation area, he explained: “We discovered a large temple with a prayer platform and a platform for offerings. A total of 73 raised stones were found on the offering platform, suggesting a deeply religious society where ritual beliefs played a central role. This evidence points to Chega Sofla being a prominent ritual center in the 5th millennium BC.”

One surprising aspect of the excavations was the social prominence of women. “We identified 102 burials, more than half of which belonged to women. The evidence indicates that women held superior positions and decisive roles in society,” Moghaddam said.

He highlighted a notable example: “Next to a mass grave of 52 individuals, we found the burial of a 25-year-old woman, whom we named Khatun. She was buried with great care and accompanied by a weight and a sword—symbols reminiscent of a goddess of justice. This suggests she held authority and a role in maintaining law and order during her lifetime.”

Further evidence reinforced this female-centered social structure: “In an 11-person brick grave, the last individual buried was a woman, and among the deformed skulls, female specimens outnumbered males. Together, these findings paint a clear picture of women’s central role in Chega Sofla society.”

Looking ahead, Moghaddam emphasized the importance of uncovering the main temple. “Based on the evidence, we are confident that the main temple exists in the residential area, though it has not yet been discovered. This makes continued excavations essential.”

Regarding daily life, he explained: “The people of Chega Sofla were skilled craftsmen—metalworkers, potters, stonemasons, spinners, and artists. They had a self-sufficient economy but also extensive trade networks, importing raw materials like obsidian, marble, and metals from distant regions.”

Moghaddam concluded: “Chega Sofla has yet to reveal many of its secrets. The pristine layers, the great temple, and the details of the society’s social and economic structure all require further excavation to present a fuller picture of one of the Persian Gulf’s earliest centers of civilization.”