SAEDNEWS: In the most popular stories about the Persian Empire, women rarely make an appearance. When they do, they are usually portrayed as minor, short-lived figures—reclusive or entangled in personal grievances within the king’s harem—but almost none of these portrayals are accurate.

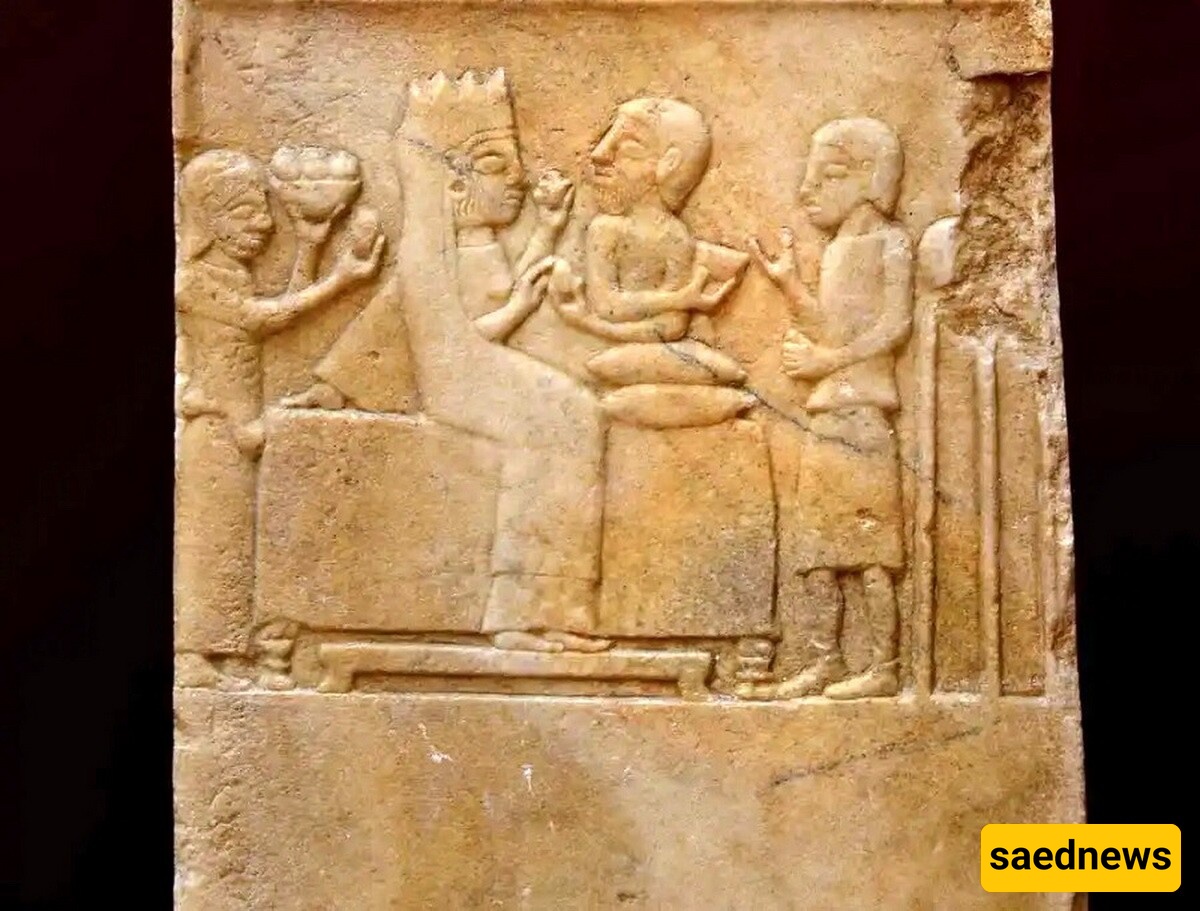

According to Saed News’ History Service, Iranian queens, as mothers of future princes, had a profound impact on royal succession and the political wealth of the Achaemenid Empire.

Queen Atossa was arguably the most royal woman in the Persian Empire. Daughter of Cyrus the Great, the empire’s founder, she was both wife and sister to two of Cyrus’s successors. By the time many of her close relatives had passed, she had become the family’s central figure.

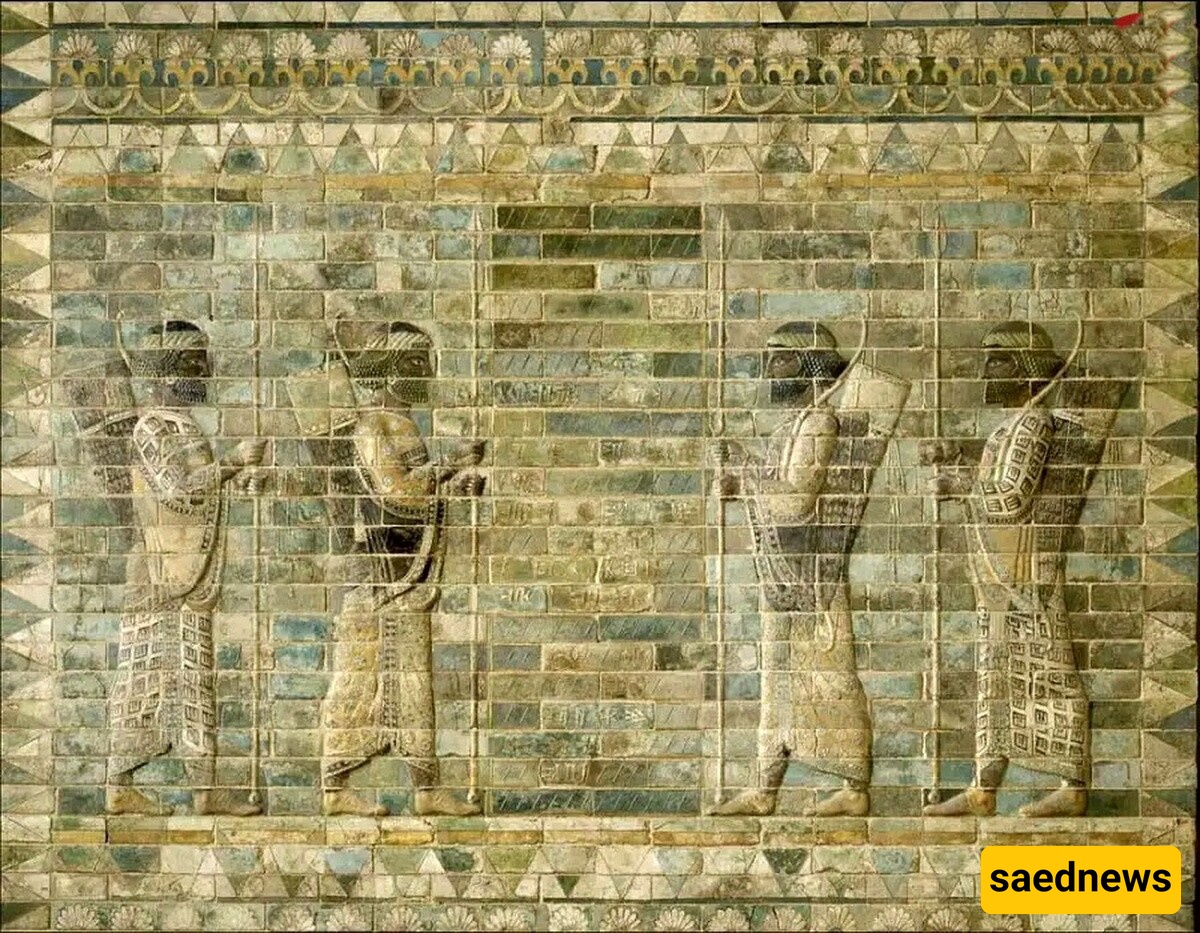

When Darius seized power, he married all surviving royal women from Cyrus’s household, including Atossa, to consolidate his rule. The goal was to ensure that the sons of these women were also Darius’s sons, merging his family with Cyrus’s bloodline. The Persepolis Fortification Archive reveals that Atossa and other royal women controlled their own property, traveled independently, and managed imperial resources. Interestingly, Atossa’s name appears less frequently than others, such as her sister Artozostre or sister-in-law Irdabama, who were more prominently recorded.

Atossa (c. 550–485 BCE), daughter of Cyrus the Great, was the wife of Darius I and mother of Xerxes I. Greek historians describe her as Darius’s most influential spouse, known for ambition, intelligence, and authority. She owned an estate called Antarantis in northern Parthia, overseeing over 100 servants and laborers, including Assyrian women and children, craftsmen from across the empire, and a Greek physician. She presided over grand festivals, performing ceremonial and religious duties typically done by the absent king.

Atossa likely resided in Parthia to remain close to her eldest son, Xerxes. According to Greek historian Herodotus, she persuaded Darius to name Xerxes as his heir, despite Darius having two sons from his first wife, whom he reportedly favored. Through Atossa’s intervention, Xerxes gained dual inheritance rights: he was both Darius’s eldest son and Cyrus’s eldest grandson, solidifying his claim. Once Xerxes became king, Atossa’s influence soared, making her the first queen mother in Persian history. She set the precedent for royal women to intervene in cases of treason, a power that Greek historians exaggerated, claiming she masterminded Persian attacks on Greece—an overstatement, yet a testament to her fame.

Amestris, succeeding Atossa as queen mother, was the most prominent wife of Xerxes I. Daughter of a key ally of Darius, her marriage strengthened political alliances.

After Persia’s failed campaign against Greece in 479 BCE, Amestris reacted violently when Xerxes gave a gift meant for her to a younger woman. Misinterpreting the situation, she punished the older woman brutally. Only Persian women could be the king’s legal wives; such breaches threatened succession and could spark civil war.

Following Xerxes’s assassination in 465 BCE, Amestris wielded her influence as queen mother to punish threats to the Achaemenids. During Ardashir I’s reign, she compelled loyal satraps to enforce her will, even overruling their oaths when necessary. Her interventions, including in Egypt and Assyria, showcased her role in maintaining dynastic stability, blending political cunning with ruthlessness.

Amestris witnessed the growth of at least two grandchildren and died naturally a few months after Ardashir in 424 BCE.

The death of Ardashir I sparked a civil struggle among his sons, both legitimate and from Babylonian concubines. Parysatis, wife of Darius II, played a decisive role in securing her husband’s power and later influencing succession.

From a young age, Parysatis was a shrewd investor and landowner, independently managing estates in Syria. She used her wealth and connections to support her son, Cyrus, against rivals. Her strategic planning included orchestrating political alliances and suppressing rebellions, ensuring Cyrus eventually gained authority in the Aegean provinces. Despite setbacks, Parysatis secured her son’s position through careful manipulation and decisive interventions, illustrating the heights of queenly influence in ancient Persia.

Unlike many earlier queens, Stateira I never fully wielded her power, overshadowed by her mother-in-law, Parysatis. She spent much of her life contending with Parysatis’s dominance and only gained political activity after Ardashir II’s coronation.

Breaking tradition, Stateira traveled openly in chariots, interacted with the populace, and earned respect, influencing the royal court’s engagement with subjects. After Cyrus the Younger’s revolt, she attempted to mediate between Parysatis and other factions but ultimately became a victim of court intrigues and poisoning, showing the precarious balance of female influence in the Achaemenid palace.

Atossa II, the youngest daughter of Parysatis, married into the royal line after Stateira I’s death. She skillfully used her position to shape succession, supporting Ochus over other candidates.

Through careful plotting and alliances, she eliminated rivals and ensured Ochus’s claim. Upon his ascension as Artaxerxes III, Atossa II became queen, wielding the remaining influence of the Achaemenid queens. Her fate, like many in the tumultuous final years of the empire, remains uncertain; if alive in 338 BCE, she likely perished during the violent purge that followed. With Alexander the Great’s conquest, no Iranian queen held comparable power for centuries.

These queens were far more than ceremonial figures—they shaped dynasties, steered imperial politics, and left legacies that outlived their lifetimes. Their stories reveal how maternal authority intertwined with empire-building in ancient Persia.