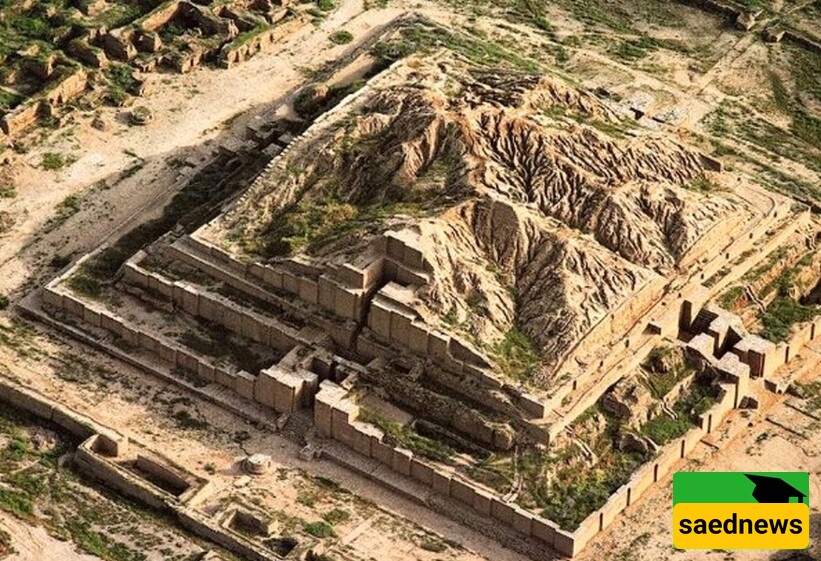

SAEDNEWS: When French archaeologists led by Roland de Mecquenem examined this mound, they discovered the ruins of an ancient city. Further investigations revealed a ziggurat at the heart of the site, considered the largest ziggurat outside of Mesopotamia.

According to the History and Culture Service of Saed News, Chogha Zanbil was first spotted in 1935 from an aerial survey plane searching for oil in Khuzestan. This monumental structure is one of the few ziggurats built outside Mesopotamia.

A team of oil explorers, acting on reports by the renowned French geologist Jacques de Morgan, came across an unusual mound during a reconnaissance flight over Khuzestan in 1935. They reported the discovery to the Iranian Archaeological Organization, which, in turn, contacted a French archaeological mission excavating near Susa, the ancient capital of the Elamite kings.

When the French archaeologists, led by Roland de Mecquenem, examined the site, they uncovered the ruins of an entire city. Further study revealed a ziggurat at the heart of the ruins—considered the largest ziggurat outside Mesopotamia.

Local residents called the mound Chogha Zanbil, meaning “basket-shaped mound.” This name eventually became the official designation, and excavation began in 1936 under de Mecquenem.

The French team identified the mound as ancient Dur Untash, or the city of Untash, built by the Elamite king Untash-Napirisha, a descendant of a powerful dynasty that ruled the region from the early 13th century BCE.

Elam stretched across the eastern plateau and northern Persian Gulf, straddling modern-day Iran and Iraq. It was a loose confederation of rulers, with the main king reigning from Susa. The local people called themselves Hatamti (Haltamti). The term “Elam” gained popularity among archaeologists after they encountered the Hebrew designation in multiple Old Testament references.

One Elamite king, Kedor-Laomer, appears in Genesis 14, said to have ruled simultaneously with the Sumerian king Hammurabi in the 18th century BCE. While this claim rests solely on biblical accounts and historians cannot confirm Kedor-Laomer’s historical existence, these references underscore Elam’s significance.

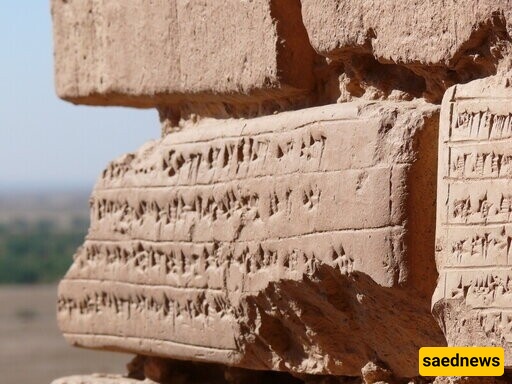

The name Elam also appears in Akkadian and Sumerian texts, meaning “highlands” or “elevated land.” The Elamite language has no known relatives, and their script remains undeciphered, leaving much of their early history to be reconstructed from Mesopotamian sources. Scholars believe the Elamites were indigenous to the Iranian plateau, with their culture emerging during the Ubaid period (c. 5000–4100 BCE).

Excavations at Chogha Zanbil were suspended in 1939 due to World War II. It wasn’t until 1951 that Roman Ghirshman, the new head of the French mission in Iran, resumed work, continuing until 1962.

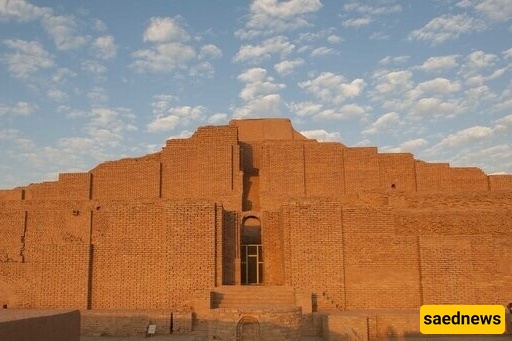

Born in Ukraine, Ghirshman had migrated to France after the 1917 Russian Revolution and had conducted major archaeological projects, including excavations at the Sassanian city of Bishapur and the Kushan city of Begram in Afghanistan. Under his leadership, the team excavated the mound and revealed a stepped pyramid—a ziggurat.

Ghirshman determined that the three-tiered structure had originally included five levels (including a temple atop) and may have risen over 51 meters, twice the height of the remaining ruins.

Ziggurats were the pinnacle of Mesopotamian architecture. While most Mesopotamian ziggurats were discovered in poor condition, Chogha Zanbil is an exception: the largest outside Mesopotamia and one of the best-preserved.

Ghirshman and his team conducted nine excavation seasons at Chogha Zanbil, meticulously uncovering Elamite structures. A royal district near the city’s protective walls contained several smaller temples surrounding the towering ziggurat.

The ziggurat dominated Dur Untash’s central sacred area, where Ghirshman uncovered temples dedicated to Elamite deities, including Pinikir, the mother goddess. Beyond the sacred precinct lay a royal district of intricately decorated palaces made of brick, plaster, and glass. Underground, a hypogeum contained vaulted burial chambers.

Scholars believe the ziggurat was dedicated to Inshushinak (god of the earth) and Napirisha (god of Susa). By honoring these deities, Untash-Napirisha may have sought to elevate the city beyond a local religious center, increasing Susa’s regional prominence.

During Untash-Napirisha’s reign, the Elamite kingdom flourished, producing remarkable art such as the bronze statue of Queen Napir-Asu, discovered alongside other treasures at Chogha Zanbil.

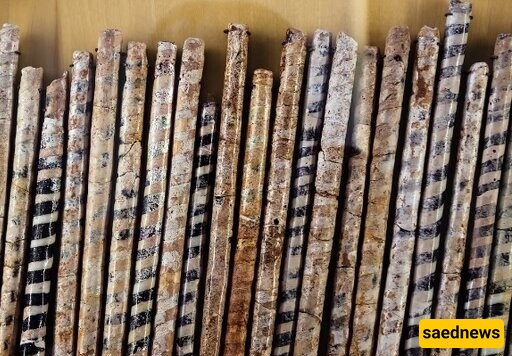

Archaeologists found that the ziggurat was built in two main stages. Initially, it consisted of a square courtyard with surrounding rooms, all opening onto the central courtyard. In the second stage, entrances were sealed, and second, third, and fourth levels were constructed as solid brick volumes above the courtyard. Access to previously open rooms was achieved via staircases from the first floor. The topmost fourth level held the high temple.

After Untash-Napirisha’s death, construction ceased, tiles remained stacked unused, and royal burial chambers were left empty. The site survived looting and became a pilgrimage destination until about 1000 BCE, after which it was abandoned.

Elam was a significant regional power in the first millennium BCE. In the mid-7th century BCE, Ashurbanipal and the Assyrians looted Chogha Zanbil but did not destroy it completely. A century later, under the Achaemenids, Elam was integrated into the Persian Empire, and its treasures remained forgotten for 2,500 years until rediscovery during the colonial and oil era.

Chogha Zanbil became the first Iranian historical site to be inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage List on October 26, 1979 (4 Aban 1358), thanks to the efforts of the late archaeologist Shahriar Adl. The ziggurat lies near Susa in Khuzestan Province, a remarkable testament to Elamite ingenuity and devotion.