SAEDNEWS: Researchers Suggest Revisiting Opium’s Expiration Date After Examining 2,500-Year-Old Marble Vessel

According to Saed News’ social affairs service, a new study indicates that opium consumption in ancient Egypt was likely part of daily life, rather than limited to ritualistic or occasional use. This conclusion is based on a chemical analysis of an alabaster vessel—made from a semi-translucent form of limestone—dating back roughly 2,500 years, in which researchers identified specific opioid compounds.

Published recently in the Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology, the findings prompt a reconsideration of certain historical assumptions and offer a fresh perspective on the everyday lives of both ordinary people and the elite in ancient Egypt.

Andrew Koh, a researcher at Yale University’s Peabody Museum, said in a statement: “Our findings, alongside previous research, suggest that opium use across various ancient Egyptian cultures and surrounding regions was more than incidental or occasional; it was, in fact, a consistent part of daily life.”

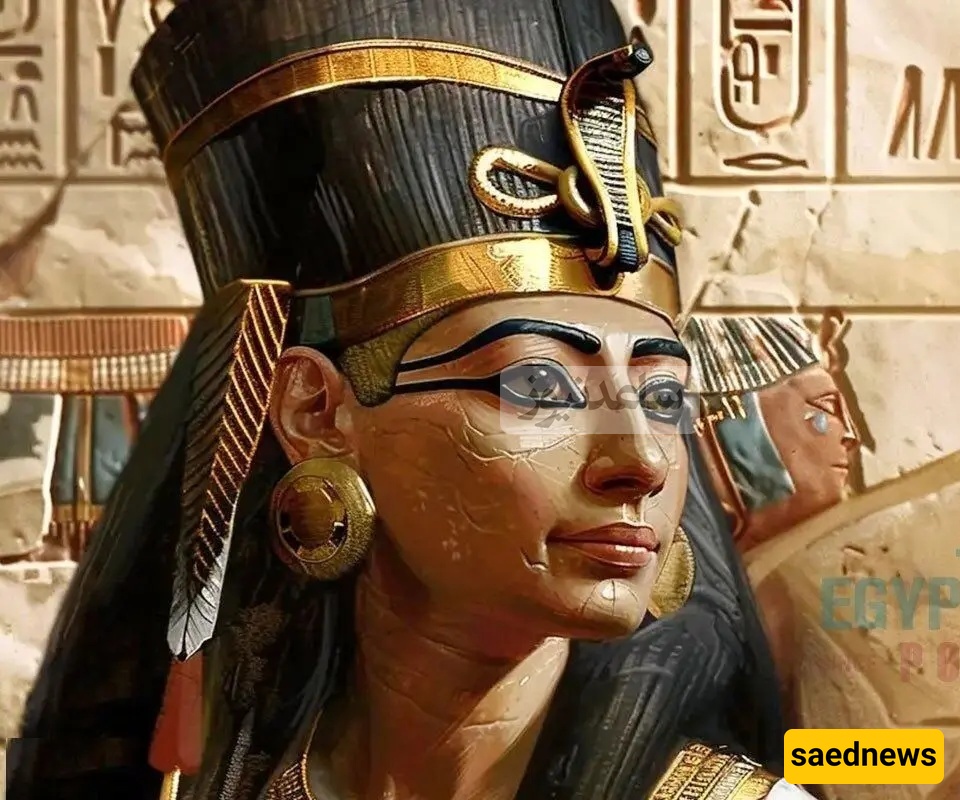

Koh and his team examined a roughly 2,500-year-old alabaster vessel, concluding that historical narratives may require revision. This object is one of ten similar, intact examples discovered at archaeological sites worldwide.

These vessels, made from calcite, have been found at several ancient sites, including the tomb of the famous Pharaoh Tutankhamun. The particular vessel studied contained inscriptions in four languages—Egyptian, Akkadian, Elamite, and Persian—addressed to Xerxes I, the Achaemenid king who ruled from 486 to 465 BCE.

During his reign, Xerxes controlled Persia, Egypt, large parts of Mesopotamia, Anatolia, the eastern Arabian Peninsula, Central Asia, and the Levant.

Koh explained: “Scholars often study ancient vessels for their aesthetic qualities, but our research focuses on how they were used and the organic substances within them.” He added that such findings shed light on previously obscure aspects of daily life in the past.

Koh’s interest in the vessel was piqued when he noticed unknown brown, fragrant residues inside. Subsequent chemical analysis confirmed the presence of noscapine, thebaine, papaverine, hydrocotarnine, and morphine—all clear indicators of opium.

The study authors note that this discovery is the latest in a broader collection of evidence, demonstrating that opium-infused vessels were not restricted to the elite. Archaeologists had previously found traces of opium in jars belonging to merchant families from the New Kingdom period (16th–11th centuries BCE).

Koh emphasized: “We’ve now detected chemical traces of opioids in Egyptian alabaster vessels. These opium-laden vessels have been found among the upper classes in Mesopotamia as well as in ordinary sites within Egypt, showing that opium use was not exclusive to the elite. In antiquity, such vessels may have served as cultural markers for opium consumption, much like hookahs today are associated with tobacco use.”

As supplementary evidence, the researchers reference a nearly century-old study by chemist Alfred Lucas. In 1922, Lucas was part of Howard Carter’s team that discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb in the Valley of the Kings. In 1933, he conducted a brief chemical analysis of similar alabaster vessels, describing their sticky, dark brown organic residues. Although he could not determine the precise aromatic compounds, he concluded they were not perfumes or similar scented products.

Koh said: “We believe that it is highly likely—if not almost certain—that the alabaster vessels found in Tutankhamun’s tomb also contained opium; they were part of an ancient tradition of opioid use that we are only now beginning to uncover.”

He hopes to conduct similar analyses on other historical artifacts, all currently housed at the Grand Egyptian Museum in Giza.