SAEDNEWS: Despite their fame, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon remain largely a mystery, with no definitive evidence of their existence or exact location. They were likely built by either Nebuchadnezzar II or Sennacherib, intended to showcase the kings’ power and delight their queens.

![The Hanging Gardens of Babylon: The Most Mysterious Wonder of the Ancient World — Step Into an Otherworldly Realm [Photos]](https://en.saednews.com/storage/files/post/2b6543e9-0c06-4547-8add-8f71dc226919-BunKuihNZl935P74/image.jpg)

Despite their fame, the Hanging Gardens of Babylon remain largely unknown, with no definitive evidence confirming their location—or even their existence. According to the Social Service Desk of SaedNews, although the gardens are celebrated as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, we still don’t know exactly where they were or whether they truly existed. Among the seven wonders recorded by Greek writers and travelers, the Hanging Gardens stand out as the most distant and enigmatic. They are the only ancient wonder archaeologists have yet to identify—and may never have been in Babylon at all.

Quick Facts About the Hanging Gardens of Babylon

Date of Construction: Early 6th century BCE (or possibly early 7th century BCE)

Builders: Nebuchadnezzar II, king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire (or Sennacherib, king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire)

Location: Babylon (or Nineveh)

Features: Terraced gardens atop stone arches

Destruction: Unknown

What Were the Hanging Gardens of Babylon?

The Hanging Gardens are listed among the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World but have remained hidden from archaeologists and historians alike. No definitive archaeological evidence has been found to pinpoint their location or appearance. Instead, knowledge comes from scattered textual references.

The earliest written mention comes from Berossus, a Babylonian priest of Marduk. His description, preserved by the Jewish historian Flavius Josephus during the reign of Vespasian and the Flavian emperors, depicts gardens with “stone terraces” shaped like “hills.”

Greek geographer Strabo elaborated: the gardens were “arched terraces stacked upon one another, resting on cubical pillars. The pillars, arches, and terraces were made of baked brick. Water was constantly drawn from the Euphrates to irrigate the gardens.”

While the exact design remains debated, it is clear that the gardens were lush even 500 years after construction—enough to earn their place among the Seven Wonders recorded by Antipater of Sidon.

Who Built the Hanging Gardens?

Legend holds that Nebuchadnezzar II, the second king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, was responsible for constructing the Hanging Gardens.

Nebuchadnezzar ascended the throne in 605 BCE following the death of Nabopolassar and ruled for 43 years—a notably long reign in the ancient world. He is remembered both for his military campaigns, including the conquest of Jerusalem and the deportation of the Jewish people to Babylon, and for his ambitious building projects.

Much of his architectural attention focused on the capital, Babylon, though other cities benefited as well. Temples such as Esagila, dedicated to Marduk, and the ziggurat Etemenanki were rebuilt during his reign. Some scholars even link Etemenanki to the biblical Tower of Babel.

Whether Nebuchadnezzar himself built the gardens remains debated, as later Hellenistic sources offer conflicting accounts.

A Garden of Love?

According to Berossus, the gardens were not merely an act of grandeur or devotion to tradition—they were a symbol of Nebuchadnezzar’s love for his wife, Amytis.

Amytis, daughter of the Median king, was married to Nebuchadnezzar to cement an alliance between the two nations. Away from the verdant mountains of her homeland, she reportedly longed for greenery. Berossus writes that Nebuchadnezzar ordered the creation of lush gardens to help his wife adjust to Babylon, with terraces and foliage evoking her native land.

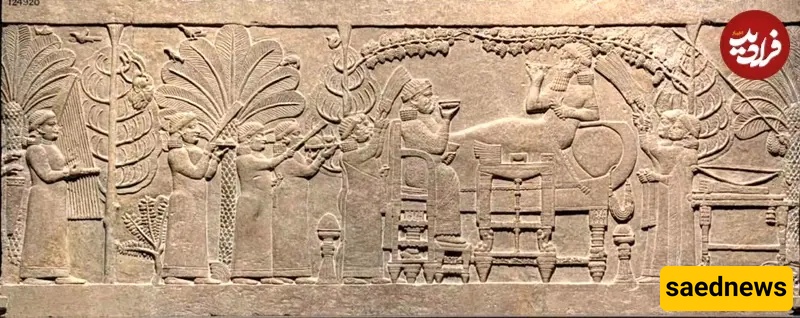

The Cultural Significance of Gardens in Ancient Mesopotamia

Evidence suggests that large gardens held great value in Mesopotamian civilizations. The modern word “paradise” may derive from the region’s languages: the Old Persian pairi-daeza meant “enclosed space” (pairi) “built or constructed” (diz) and referred to walled gardens.

Gardens were not only aesthetic—they were symbols of imperial power. Trees and shrubs were often transplanted to display a ruler’s wealth and reach, much like palm trees on Roman coins commemorated the Flavian conquest of Judea. Advanced irrigation systems enabled the construction of such gardens, likely incorporating exotic plants from across empires. Similar techniques were used in the gardens of Ashurbanipal, king of the Neo-Assyrian Empire, aligning with Berossus’s account of Amytis’s longing.

Controversy: Were the Gardens in Nineveh?

Given the absence of archaeological evidence for Babylon’s legendary gardens, could they have been misattributed?

Stephanie Dalley, an Oxford scholar of the ancient Near East, suggests that the gardens listed among the wonders might have been built by Sennacherib, king of Assyria (704–681 BCE)—nearly a century before Nebuchadnezzar.

Sennacherib, son of Sargon II, was known for military campaigns, though he spared Jerusalem. He destroyed Babylon in 689 BCE, later rebuilt by Nebuchadnezzar. Sennacherib’s building projects included a southwestern palace and extensive gardens adjoining the palace in Nineveh.

Only Berossus, via Josephus, directly attributes the gardens to Nebuchadnezzar, so it is possible the Hanging Gardens of Babylon were actually Sennacherib’s creation. The discovery of an extensive canal system attributed to Sennacherib supports the theory that these irrigation networks could have sustained terraced gardens similar to those described.

The Enduring Mystery

The Hanging Gardens of Babylon remain one of the ancient world’s most tantalizing mysteries. Their precise location, builder, purpose, and fate are still unknown. The lack of archaeological evidence has ensured that the gardens—the second wonder of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World—remain tantalizingly out of reach.