SAEDNEWS: Archaeologists in 2010 discovered the 1,300-year-old tomb of a woman who, after her death, gave birth in her child’s grave.

In the 7th or 8th century CE, during the Middle Ages, a pregnant woman died and was buried in the Italian city of Imola. At the time, there was nothing unusual about her death. However, when her grave was discovered in 2010, researchers noticed two highly unusual features. First, a cluster of small bones was found between the woman’s legs—the remains of a fetus that had apparently been born after the mother’s death. Second, a small hole in the mother’s skull complicated the mystery of her death.

According to researchers, a study published in World Neurosurgery investigates the events before and after her death. The remains were found in a stone grave with an arched structure, suggesting intentional burial. Analyses conducted by scientists at the University of Ferrara and the University of Bologna indicated that the woman was between 25 and 35 years old at the time of her death. Her fetus, whose sex could not be determined, was apparently at 38 weeks of gestation, only two weeks shy of full term.

While the baby’s legs remained inside the mother’s body, the head and upper torso had apparently emerged post-mortem. The study’s authors suggest that this is a rare example of post-mortem fetal extrusion, a phenomenon that occurs when gases accumulate in a deceased pregnant body, forcing the fetus out of the birth canal. Such cases are extremely rare in archaeological records.

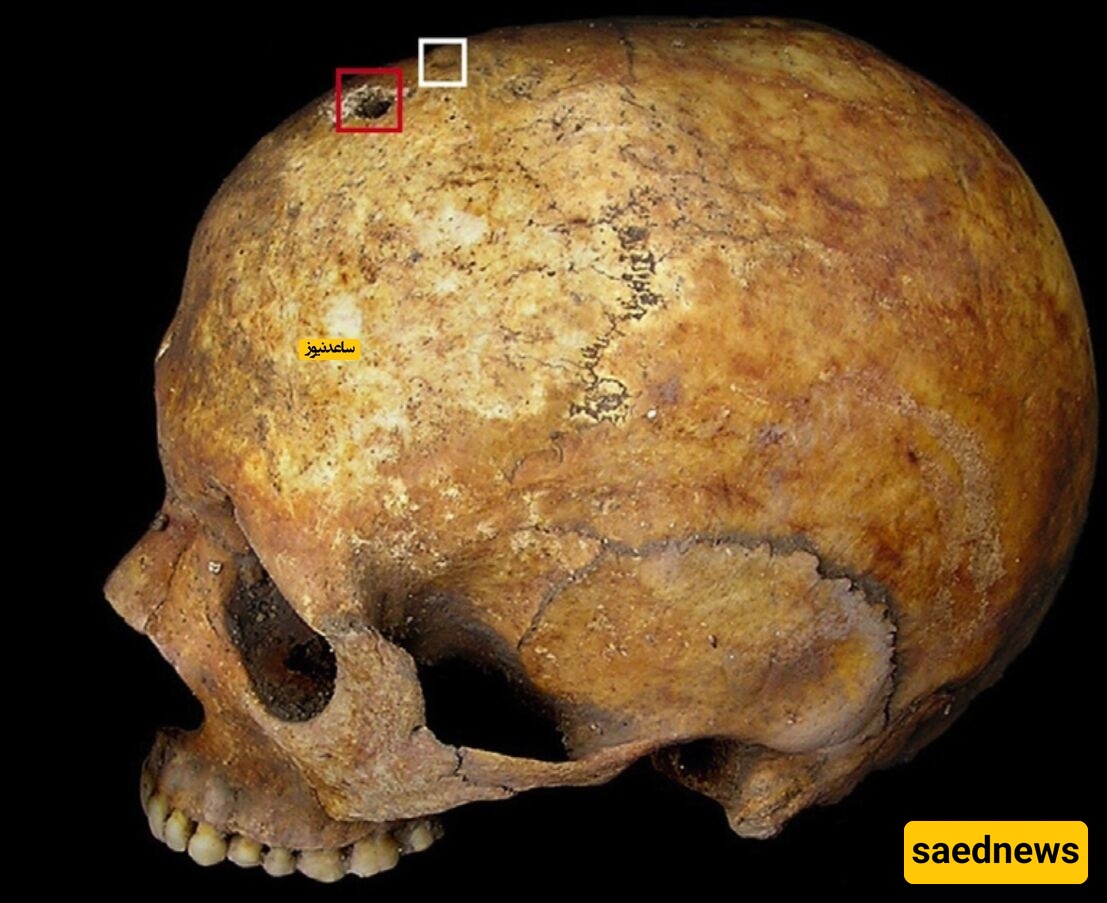

The researchers were also intrigued by the unusual hole in the woman’s skull. Measuring 4.6 millimeters in diameter, it was smooth and clean, indicating it was not caused by a violent attack. Most likely, the hole was created as part of a surgical procedure known as “trepanation.” This practice likely dates back to the Neolithic era and was believed to treat a range of conditions, from high fevers to seizures and intracranial pressure. The skull also showed narrow incision marks, suggesting careful removal of scalp tissue to prepare for the trepanation.

Why would medieval physicians perform such a risky operation on a pregnant woman? Researchers are not certain, but they hypothesize that the mother may have suffered from pregnancy-related high blood pressure or eclampsia. Common signs of these conditions include increased intracranial pressure and brain hemorrhage, which were historically treated with trepanation before modern medicine.

Signs of healing in the skull suggest that the woman survived approximately a week after the surgery. It remains unclear whether her death was caused by pregnancy complications, the surgery itself, or another underlying illness. While evidence of trepanation has been found in many archaeological remains, signs of the procedure are rare in medieval skulls.