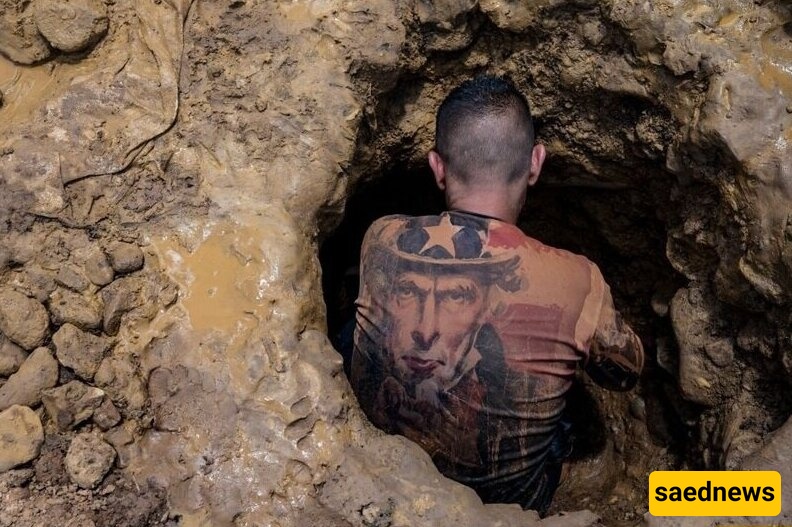

SAEDNEWS: The small, agile bodies of children help them navigate narrow shafts and pull out mud, hoping it contains gold—a precious commodity that has grown even more valuable as Venezuela’s oil production declines.

According to Saad News’ society service, around 1,000 children work in illegal gold mining in Venezuela, a booming industry in this resource-rich country.

Ten-year-old Martín cannot read, yet he has developed a particular skill in extracting gold alongside his cousins from an open-pit mine in southeastern Venezuela.

In the town of El Callao, digging gold from the soil often begins as a child’s game but quickly turns into a full-time job, condemned by human rights activists as dangerous exploitation.

The small, agile bodies of children help them navigate narrow shafts and pull out mud, hoping it contains gold—a precious commodity that has become even more valuable as Venezuela’s oil production declines.

Heavy bags of mud are washed in wooden pans after extraction. Martín explains, “Everything that is gold sticks to mercury,” a toxic substance they use to extract gold from the mine, harmful to the environment.

Martín lives in El Pro, a nearby village. He has never attended school.

Carlos Trapani, from the children’s rights NGO CECODAP, says that back-breaking labor and its associated dangers have become normalized in these communities.

Despite what Trapani describes as the worst conditions, Martín says he prefers earning gold over going to school.

In an interview with Agence France-Presse, he said: “My father says money comes from work. With the money I earn here, I buy my things: shoes, clothes, sometimes candy.”

Since 2013, Venezuela has faced a severe economic crisis, attributed by experts to political mismanagement, U.S. sanctions, and overreliance on vast oil reserves.

The country’s GDP has dropped by 80 percent, and hyperinflation has eroded purchasing power. About seven million of the country’s 30 million people have left in search of a better life elsewhere.

In 2017, Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro promised to rescue the economy by focusing on other mineral resources, claiming the country could hold the largest gold reserves in the world.

Since then, what the International Crisis Group calls “the bounty of illegal mining” has spread across southern Venezuela, where criminal groups—including Colombian guerrillas—control most operations, terrorizing local communities.

Eleven-year-old Gustavo, another miner, says: “When the shootings start and people are killed, I get scared.”

According to a 2021 report by the OECD, much of the gold extracted by small miners ultimately ends up in the hands of military and political elites.

In July, Maduro ordered the deployment of armed forces to expel illegal miners, and authorities reported the destruction of some camps.

Mining, mostly in Venezuela’s Amazon region, has devastated the environment and indigenous communities. In some areas, including El Callao, a gram of gold is used as currency in local businesses instead of the bolívar.

This can benefit child miners like Gustavo. He said: “Yesterday I got one gram [worth about $50]. I gave the money to my mom to buy food.” He has been mining since he was six and does not attend school.

Children in Venezuela, who make up a third of the population, have borne the brunt of this crisis. Trapani said that at the height of the economic crisis in 2018, not only did schoolchildren head to the mines, but teachers also left their daily jobs to work there.

Gustavo’s mother said her children did not return to school after the COVID-19 lockdown, though she hopes they eventually will.