Saed News: Researchers around the world are trying to uncover the origin of the mysterious iron dagger belonging to Tutankhamun, the famous pharaoh of ancient Egypt. However, they do not all agree on the results obtained.

According to the history section of Saed News, quoting ISNA, researchers around the world are trying to uncover the origin of the mysterious iron dagger of Tutankhamun, the famous pharaoh of ancient Egypt. However, they do not all agree on the results.

Archaeologists were astonished when they discovered that the dagger found in Tutankhamun’s tomb was made using material of extraterrestrial origin. Now, two new studies are shedding more light on the origins of this mysterious weapon, which belonged to Egypt's most renowned pharaoh.

According to one of the studies, the dagger — made from meteoritic iron — was crafted in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). However, another study claims that the exact terrestrial origin of the dagger’s production remains undetermined.

At the time of Tutankhamun’s reign (1333–1323 BCE), smelting had not yet been invented, which meant iron was a rare and precious material, often derived from meteorites.

One recent study, published on February 11, notes that the adhesive material used in attaching the golden hilt of the dagger was commonly used in Anatolia during Tutankhamun's time — but not widely in Egypt.

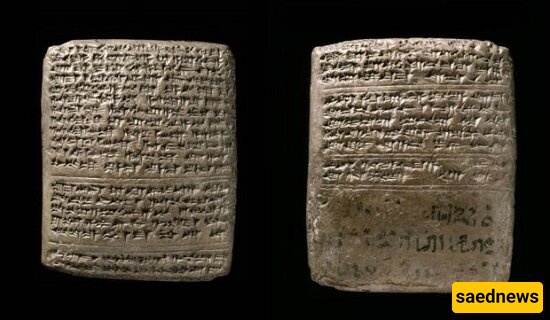

Additionally, historical documents (a collection of 3,400-year-old tablets) discovered in Amarna, Egypt, indicate that Tushratta, the king of Mitanni in Anatolia, had gifted at least one iron dagger to Amenhotep III, Tutankhamun’s grandfather.

However, another study, published in the book Iron from the Tomb of Tutankhamun, concludes that it's currently impossible to definitively determine the origin of Tutankhamun’s iron artifacts.

The authors point out that the crystal stone used in the dagger resembles those commonly found in Aegean artifacts, though the dome-shaped pommel matches typical Egyptian styles. This suggests the dagger could have been made in Egypt — or perhaps produced elsewhere specifically for the Egyptian market. Thus, the study concludes that the exact origins of the dagger’s blade or hilt remain inconclusive.

So what do other researchers think? Live Science contacted several scholars not involved in either study. For example, Albert Jambon of Sorbonne University, who has extensively studied ancient iron artifacts, disagrees with the Anatolian origin theory.

Jambon believes the substance researchers claim is adhesive on the dagger’s hilt was actually a cleaning material used in the 1920s on some of Tutankhamun’s items. He also emphasizes that the hilt and blade are separate pieces, potentially crafted in different places.

Marian Feldman, head of archaeology at Johns Hopkins University, adds that if the Anatolia theory is accurate, it could imply that some luxury items in Tutankhamun’s tomb were in fact diplomatic gifts from foreign lands.