SAEDNEWS: During his adolescence, Naser al-Din Shah learned daguerreotype photography from Monsieur Richard, although the first camera was introduced to Iran during the reign of Mohammad Shah.

According to the Saed News Society Service, the unintended release of several photo albums from the Qajar-era Golestan Palace on social media has sparked widespread interest among users, historians, and photography enthusiasts. Seizing the opportunity to highlight these images, we take a look at the history of photography during the Qajar period.

The first camera entered Iran in 1842, roughly three years after its invention in 1839, as a gift from Tsar Nicholas I of Russia to Mohammad Shah Qajar. Shortly afterward, Mohammad Shah also received a camera from the Queen of England.

The Russian camera was brought to Iran by a diplomat named Nikolai Pavlov, who had learned to operate it, and he is likely the person who took the first photograph in Iran, depicting Mohammad Shah. Some sources note that Mohammad Shah’s son, Crown Prince Naser al-Din Mirza, and his daughter Ezzat-od-Dowleh—who would later marry Amir Kabir—were also present in this photograph.

The cameras that arrived in Iran were daguerreotypes, and after Pavlov, no one at the Iranian court knew how to operate them, leaving the cameras largely unused. The solution came from Monsieur Jules Richard, a Frenchman who had arrived in Iran during Mohammad Shah’s reign and, after converting to Islam, took the name Mirza Reza Khan. Mirza Reza Khan played a key role in spreading photography in Iran.

At the same time, some researchers believe that Qasem Mirza, the twenty-fourth son of Fath Ali Shah, also practiced daguerreotype photography.

The flourishing of photography in Iran occurred during Naser al-Din Shah’s reign. As a teenager, he learned daguerreotype photography from Monsieur Richard and later mastered new photographic techniques under Francis Carleian. Naser al-Din Shah can thus be regarded as one of Iran’s pioneering photographers.

Under the king’s order, Agha Reza studied photography under Carleian and became the court’s chief photographer. Photography was also added to the curriculum of Dar al-Fonun School. At this stage, photography was considered a technical skill rather than an art, and photographers referred to themselves as engineers.

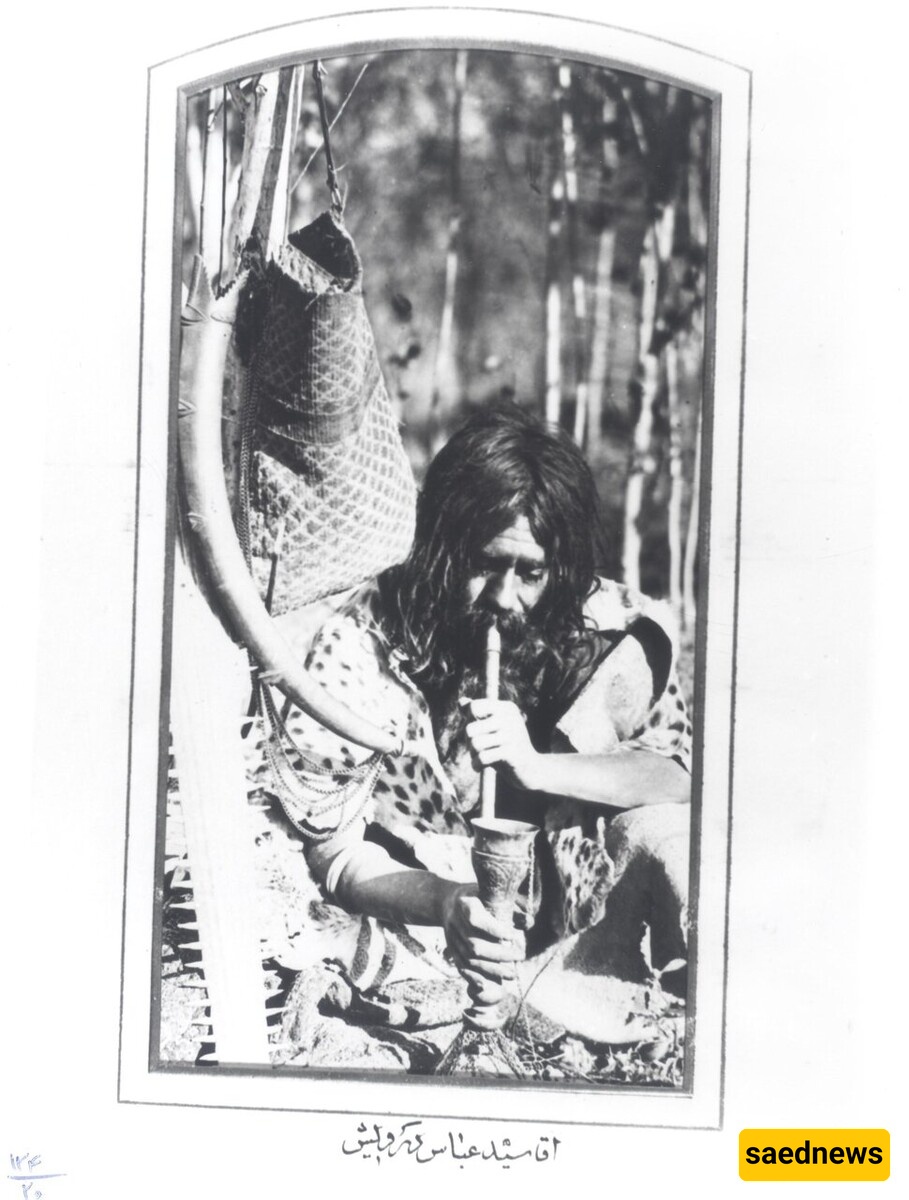

After the establishment of the Homayouni Photo Studio under Agha Reza, Naser al-Din Shah ordered the creation of a public studio managed by Abbas Ali Bey, a student of Agha Reza. Subsequently, other photo studios opened in Tehran and across the country.

An announcement marking the opening of the first public studio under Abbas Ali Bey stated: “Since most people are eager to have their photographs taken, and not everyone could go to the royal state studio, Chief Photographer Abbas Ali Bey assigned a trained assistant to set up a studio on Jebakhaneh Street (now Bab Homayoun) where anyone wishing to have their photograph taken could do so. Prices varied: a large photograph of twelve pieces cost four thousand dinars, a medium set three thousand dinars, and a small set two thousand dinars. Additional prints were priced at thirty shahis each.”

The photographs from Golestan Palace can be roughly categorized as follows:

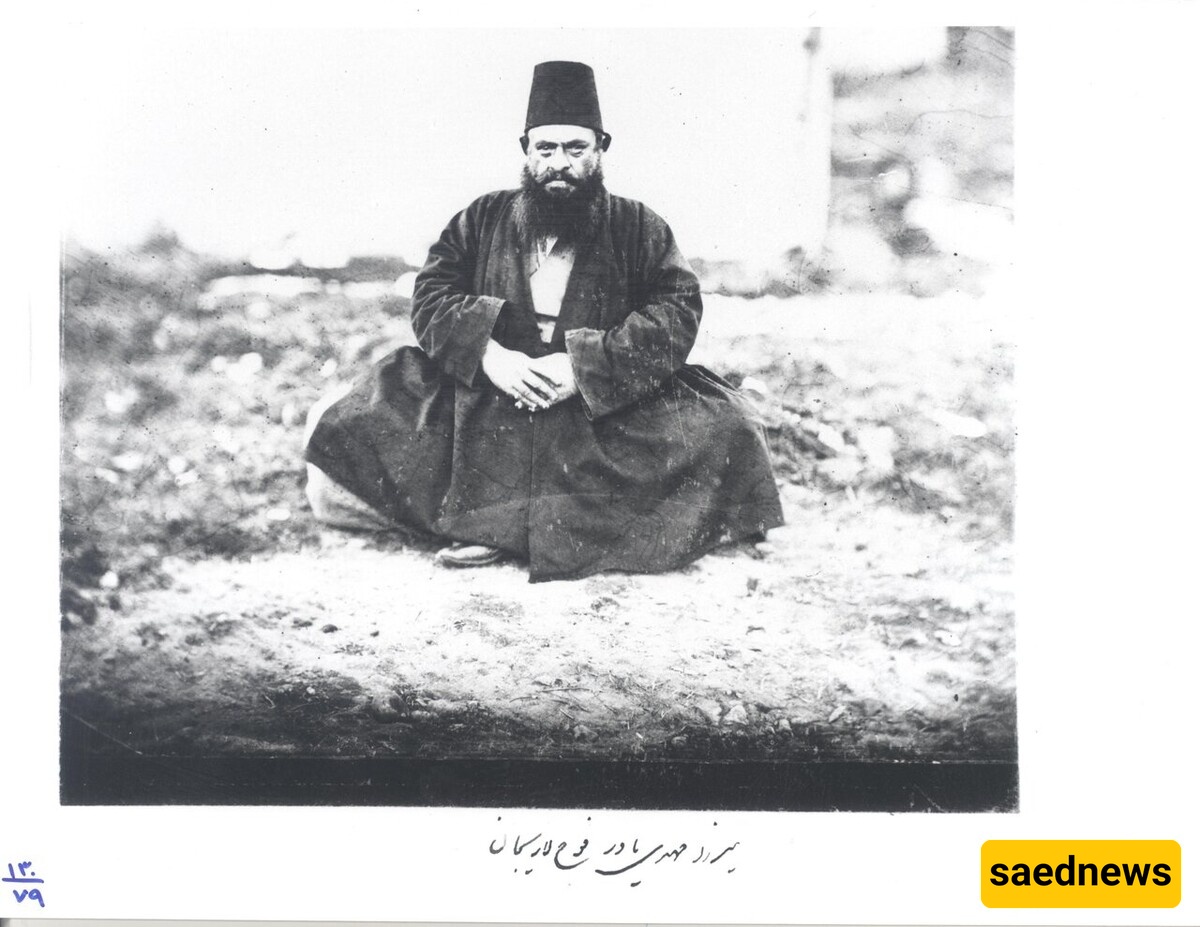

Court figures: kings, ministers, and princes

Non-official court members: women and children

Non-court elites: merchants, clerics, teachers, physicians

Lower-class non-court individuals: peasants, workers, passersby

Buildings and spaces: palaces, gardens, shrines, inns, other structures

Ceremonies: rituals, festivals, horse racing, cooking events

Animals: including Naser al-Din Shah’s cat, Babri Khan

While the quality of these leaked images differs greatly from the originals, they are nonetheless valuable, especially given the reluctance of institutions like museums and historical palaces to release their historical archives.

Sociological, anthropological, and aesthetic analyses of Qajar-era photography have been conducted by researchers such as the late Shahryar Adl and Yahya Zaka, but the release of these new photographs provides a rare opportunity for fresh studies and insights by specialists.