SAEDNEWS: Every year on the last day of autumn, Iran marks Yalda Night, an ancient festival celebrating the winter solstice, the rebirth of the sun, and the symbolic triumph of light over darkness.

Known as Shab-e Yalda or Shab-e Chelleh, this celebration spans the hours between sunset on the final day of autumn and sunrise on the first day of winter. With roots stretching back centuries, Yalda Night is one of the most significant cultural observances in Iranian history. Historical records show that it was officially included in the calendar of ancient Iran in 502 BC during the reign of Darius I, also known as Darius the Great.

Both before and after the advent of Islam, Yalda Night has held a central place in Iranian cultural life. Traditionally, it has been a time for families—near and far—to gather, strengthening social bonds through rituals that have endured for generations. The night marks the gradual lengthening of days after the solstice, symbolizing the renewal of the sun and the triumph of light over darkness.

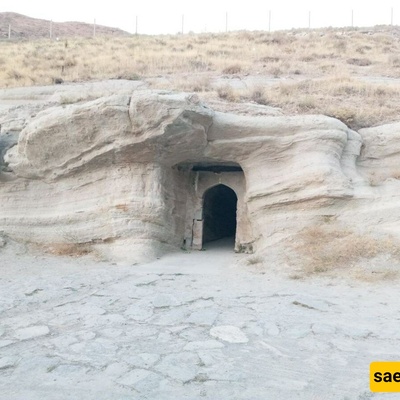

In ancient times, darkness was thought to harbor evil forces, prompting people to stay awake throughout the longest night of the year and light fires for protection. While the symbolism has evolved, the essence of the celebration—gathering together until dawn—remains unchanged.

On Yalda’s eve, Iranian households buzz with excitement as families prepare for the night. Historically, gatherings centered around open fires and, later, around the korsi—a low table with a heater beneath, draped with blankets. Today, celebrations typically take place indoors with modern heating, and Yalda is often observed as an overnight family gathering, hosted by grandparents or elderly relatives.

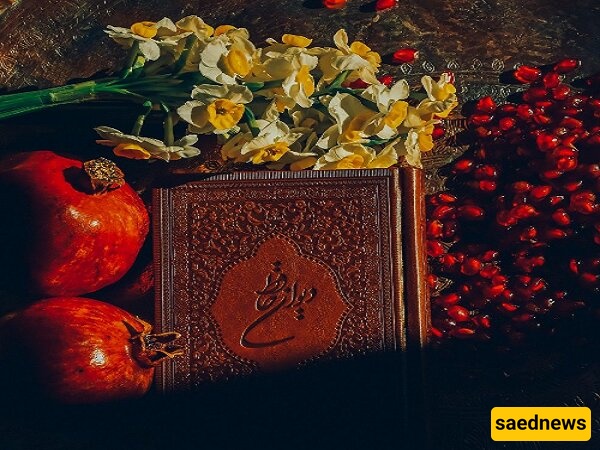

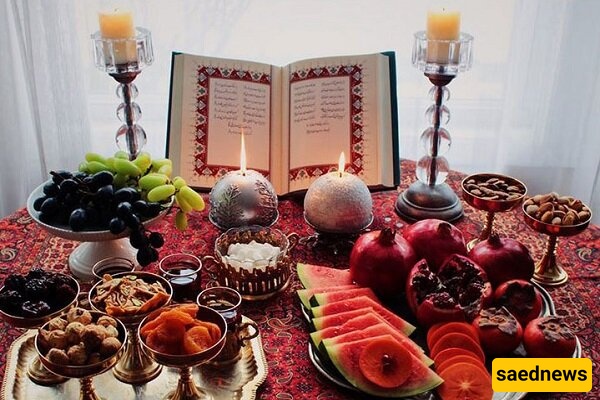

Storytelling remains a central feature. Elders recount tales and anecdotes, fostering an atmosphere of warmth and continuity. Literary traditions are equally important, especially the reading of verses from Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh and the Divan-e Hafez. A popular ritual involves each participant silently making a wish, then opening the Divan-e Hafez at random. The eldest present reads the selected poem aloud, and its verses are interpreted as a symbolic response to the wish.

Food and fruit are at the heart of Yalda Night. Families prepare a generous dinner, but the focus is on fruits and nuts. Watermelon and pomegranate are the most iconic, prized for their red color, which symbolizes the sun. The pomegranate represents fertility, blessing, happiness, and sacredness, while watermelon—despite being a summer fruit—is traditionally eaten to ward off cold and illness during winter.

Other fruits commonly enjoyed include oranges, apples, persimmons, pears, and pumpkins. Nuts such as pistachios, walnuts, almonds, and hazelnuts are essential, often paired with dried figs and berries. Across Iran, regional variations add local foods and customs, reflecting diverse cultural identities.

In eastern Iran, particularly Khorasan, a traditional sweet called kaf is prepared, and special rituals are sometimes held for newly engaged couples. Shahnameh recitation ceremonies are also common in the region.

In Tabriz, street musicians known as Ashiq perform in neighborhoods, singing, playing music, and narrating legends. In Lorestan, young people climb onto neighbors’ rooftops after sunset to sing the traditional song Shov-e Avval-e Qāreh, lowering scarves to receive treats.

In Zanjan, the korsi remains widely used, and local Yalda gatherings feature traditional sweets such as window-shaped pastries and baklava. In Sanandaj, the capital of Kordestan Province, families prepare dolma and sangak bread, taking turns hosting each year.

Recognizing its cultural importance, Yalda Night was officially added to Iran’s List of National Treasures in 2008.