SAEDNEWS: A critical overview of Western-imposed treaties on Iran, highlighting exploitative agreements and national resistance efforts.

According to SAEDNEWS, During the Qajar period and later during the Pahlavi era, due to certain contracts, treaties, or heavy concessions, portions of Iranian land or national wealth were lost, with the rulers and kings selling out the country for a small amount. Some of these contracts were thwarted by protests led by clergy, but others led to national plundering. On the occasion of the Tobacco Concession cancellation, we review some of these shameful treaties and disgraceful concessions.

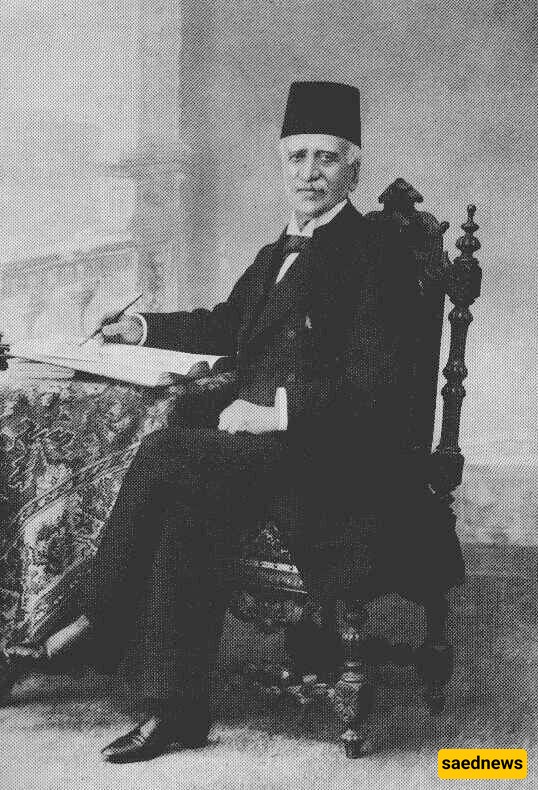

Contract Parties: Baron Julius de Reuter, a British Jew of German descent with the real name “Israel Beer Josaphat,” and the Qajar government.

Mirza Hossein Khan Sepahsalar (Prime Minister) received 50,000 pounds, Mirza Malkom Khan (Foreign Minister) 20,000 pounds, Moein al-Molk (Minister of Commerce) 20,000 pounds, and various Qajar statesmen also received bribes to sign this contract with the British.

Under this concession, Reuter was given the right to construct any roads, railways, and dams from the Caspian Sea to the Persian Gulf, exploit all mines (except gold and silver), build water channels and canals for navigation or agriculture, establish banks and any industrial companies across Iran, a monopoly on public works, the right to buy and sell tobacco, exploit forests for 70 years, and collect customs for 25 years in exchange for 200,000 pounds and a 5% interest.

Due to protests from the clergy and Russian pressure, Naser al-Din Shah annulled it before implementation. Even the British government was unwilling to support Reuter’s excessive ambitions. Reuter pursued compensation for 17 years and eventually succeeded in obtaining the Second Reuter Concession with the help of Sir Henry Drummond Wolff, British ambassador to Iran, granting him the right to establish the Imperial Bank of Persia in 1889.

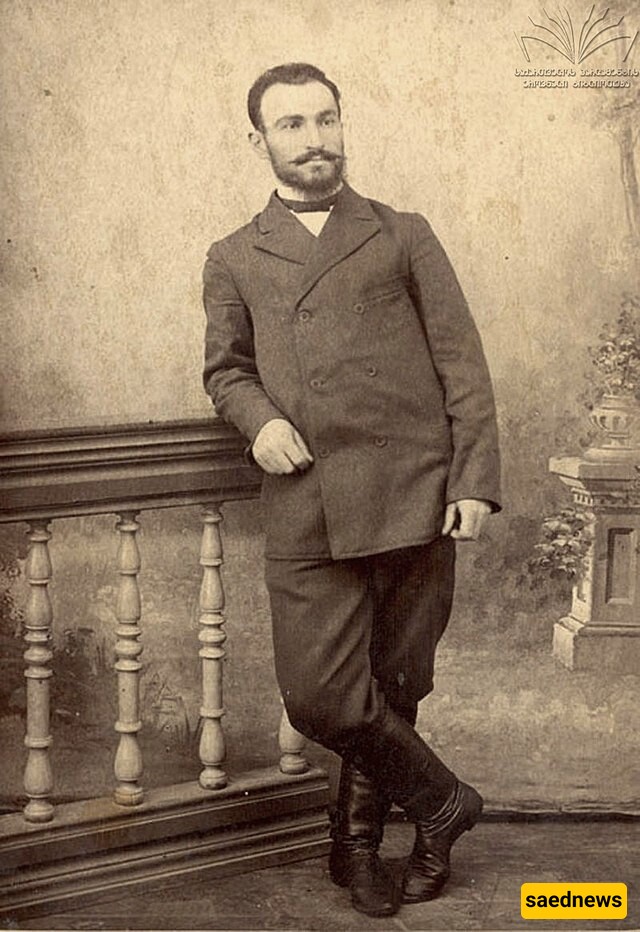

Contract Parties: Officially between Iran and Britain, but outwardly with a French citizen named Yury de Cordoual (an agent of Mirza Malkom Khan and secretary at the Iranian embassy in London) with Iran’s government.

During Naser al-Din Shah’s visit to Europe, where he met Queen Victoria, elaborate banquets were held in his honor, with long speeches on Iranian-British friendship, translated into Persian by Mirza Malkom Khan, Iran’s ambassador. While in Scotland, Malkom Khan proposed establishing a lottery system in Iran, explaining the potential revenue it could bring to the government’s treasury, and convinced the Shah that lotteries weren’t gambling but a game common across Europe.

A monopoly on lotteries and lottery-related public games like roulette across Iran for 75 years, with a 20% profit share.

After securing the contract, Malkom sold it to the English and Asia Syndicate for a 20,000-pound advance. The contract faced strong opposition in Iran, leading Naser al-Din Shah to annul it. Malkom sold the canceled concession to another company in London, claiming he had transferred the 40,000 pounds to the Iranian treasury, later declaring bankruptcy. He subsequently played a prominent role in political reforms, raising issues about law and the corruption of the lawless Qajar government.

Contract Parties: Akaki Khoshtaria, a Russian citizen, with the Iranian government.

Khoshtaria managed to obtain this concession through Russian embassy support from Prime Minister Vossough od-Dowleh.

Exploitation of all mines, including oil, in five northern provinces of Iran for 70 years, with 12% of profits going to Iran.

Khoshtaria offered a bribe to expedite the agreement, and the Minister of Culture declared the bribe as a "donation to culture." The concession was eventually annulled as it required parliamentary approval, and with the parliament in recess, the Ministry of Public Benefits declared the concession void in 1918. Khoshtaria later sold the concession to the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, causing tension in Iran-Soviet relations.

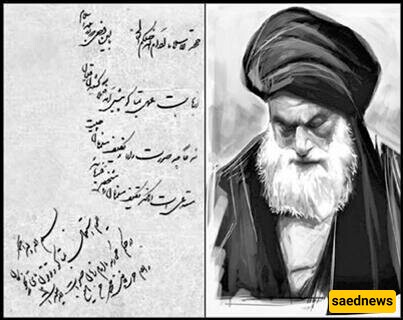

Contract Parties: The British Regie Company, led by Talbot, with Iran’s government, effectively the British government with groundwork by Major Gerald Talbot.

After Naser al-Din Shah’s third trip to Europe, the treasury was empty. Talbot, who hosted the Shah, gathered information about Iranian tobacco production, forming Regie with British government support and secretly began preparations in Iran, bribing officials, including a 25,000-pound bribe to the Shah, with a 15,000-pound annual bribe to follow.

In exchange for a monopoly on buying and selling tobacco in Iran for 50 years, Regie would pay the Shah an annual 15,000 pounds and a quarter of its net profit. Regie gained exclusive control over Iran’s tobacco trade, even overseeing its cultivation.

Mirza Shirazi issued a historic fatwa: "Today, the use of tobacco in any form is considered warfare against the Imam of the Age." Even within the Shah’s palace, hookahs were broken, and under public pressure led by Mirza Ashtiani, Naser al-Din Shah annulled the Regie Concession.

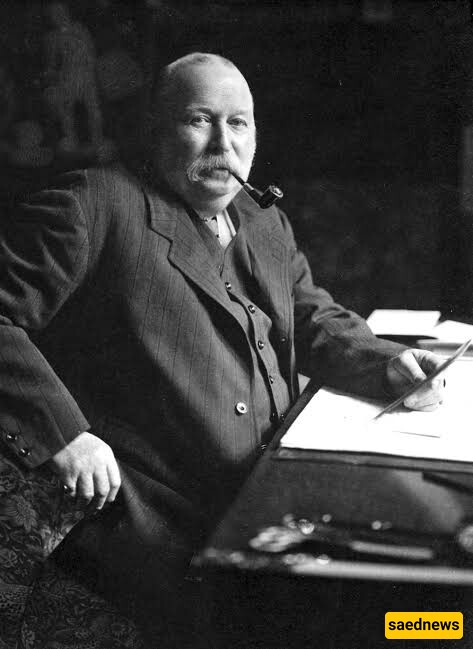

Contract Parties: William Knox D'Arcy, a British citizen, with Iran’s government.

Oil exploration and extraction.

Exclusive rights to extract and exploit oil across Iran (excluding the northern provinces) for 60 years, with an annual 20,000 pounds, shares worth the same amount, and 16% of net profits to Iran.

A year after the first oil well in Masjed Soleyman, the British established the Anglo-Persian Oil Company, using various strategies to transfer D'Arcy’s concession to themselves, paying Iran a pittance. Under Reza Shah, with the British failing to honor the full payments, he unilaterally canceled and burned the contract, leading to negotiations and the 1933 contract.

On June 28, 1933, one of the most significant colonial agreements was signed between Reza Shah’s government and British oil companies, extending England’s oil extraction rights until 1993. With only seven years into Reza Shah’s rule, the contract was approved by the ninth National Assembly, where Reza Shah banned any discussion of oil or the contract in public forums or media. The contract lasted 20 years, until the nationalization of the oil industry nullified it.