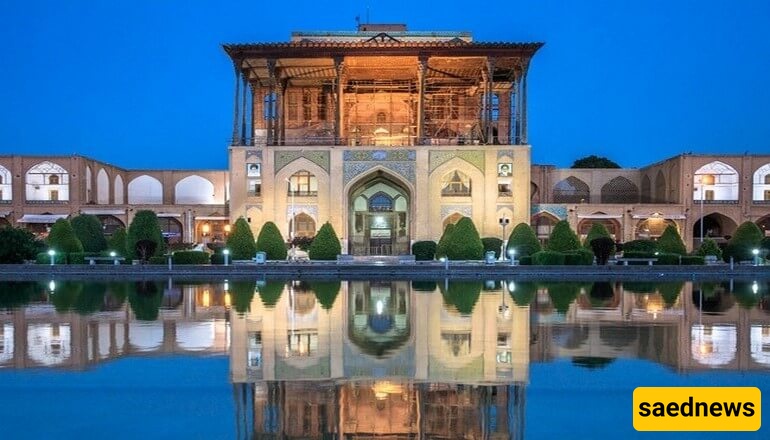

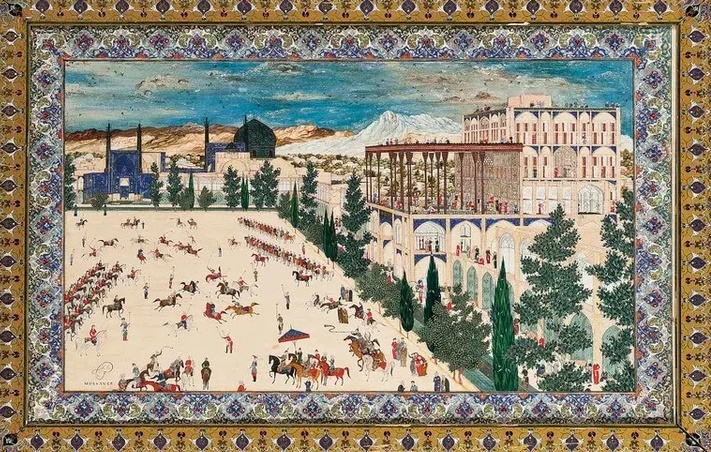

SAEDNEWS: Ali Qapu Palace is one of Isfahan’s must-see attractions. The palace dates back to the Safavid era, and in the past, kings would sit on its veranda to watch authentic and captivating Iranian polo matches in the middle of Naqsh-e Jahan Square.

Its origins date back to the height of the Safavid era, which was the most magnificent monarchy after Islam; however, since the inscriptions of Ali Qapu Palace have been lost, the exact time of its construction remains unknown! In a period when everyone and everything had to show respect to the kings and bow, it was now the turn of the Safavid monarchs to lower their heads in reverence to the turquoise-colored Sheikh Lotfollah Mosque across from Naqsh-e Jahan Square and the Shah Mosque, and not dare entertain thoughts of audacity or grandeur in the face of a mosque six stories tall.

Until a few years ago, one could not find a house among Isfahan’s tourist sites that could diminish the sanctity and grandeur of these mosques, let alone Ali Qapu Palace, which could have asserted its greatness. In other words, this was a palace meant to show the people who held power, yet in front of the two mosques, it maintained a simple, noble, and sincere presence, showing its humility at least until the Abbasid period, until Shah Abbas came and gradually added floors and lavish embellishments. The upper columned veranda, decorated with beautiful mirrors, was adorned by Shah Abbas II himself, although none of those mirrors survive today—mirrors that would shine under direct sunlight.

Now, heaven forbid, if a thug or a guilty person sought refuge from trial, they could not flee without going to Ali Qapu Palace. Whether they trusted the door dedicated to Imam Ali (peace be upon him) at the entrance or the mercy and compassion of Shah Abbas I, Iran’s greatest and most powerful king, remains uncertain. But the moment someone took refuge at the palace entrance, no one except the king had the authority to expel them. Consider the greatness of Shah Abbas: a criminal, seeking sanctuary, would ignore the two surrounding mosques of Naqsh-e Jahan and turn to Ali Qapu Palace for protection.

After a series of unusual twists, the capital needed to be moved from Qazvin to another location. One of the most beautiful and temperate tourist sites in Iran was Isfahan. Thus, Shah Abbas I, between the years 973 and 977 AH, acted to transfer the capital from Qazvin to Isfahan. If the king wanted to distinguish his capital, he had to embody it through Safavid architecture.

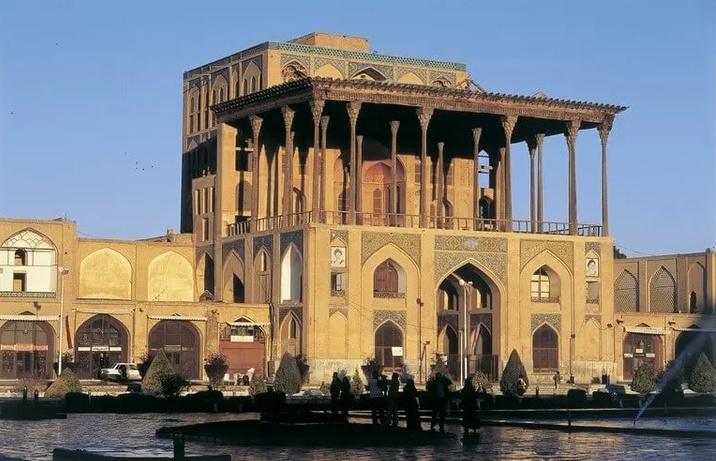

This is where Shah Abbas I ordered the construction of Ali Qapu Palace in the large and scenic Naqsh-e Jahan Square of Isfahan, to serve as a unique symbol against the Ottomans. At that time, Ali Qapu Palace was very simple. However, after the death of Shah Abbas I, it seems that Shah Abbas II and Shah Sultan Hossein also wished to transform the entrance of Naqsh-e Jahan from simplicity, adding floors to the palace.

Do not look at Naqsh-e Jahan Square or the architecture of Ali Qapu Palace and compare it to many modern palaces—most cannot even come close. It took roughly 70 to 100 years for the palace to evolve from simplicity to its current grandeur. At that time, Naqsh-e Jahan Square, an untouched area measuring 386 meters in length and 140 meters in width—comparable, if not larger, than Moscow’s Red Square—was placed under the king’s authority. The architecture of Ali Qapu Palace was registered as a national heritage site on January 5, 1932 (15 Dey 1310 in the Iranian calendar).

Although Qajar-era architecture was not far behind that of the Safavid period, as soon as they stripped the Safavids of their ruling power, they harmed Ali Qapu with complete injustice and lack of culture. Without the Safavid kings, the Ali Qapu Palace lost its majesty. It even fell so low that it became the residence of the then-governor of Isfahan, Zill al-Sultan.

The tastelessness of this governor has its own story: during the reign of Naser al-Din Shah, he demolished the palaces of Isfahan and even entertained the idea of destroying this Ali Qapu Palace, spreading his poison by applying plaster over its paintings. This was compounded by the Afghan invasions, battles, strange conflicts, mismanagement, and subservience of some post-Safavid rulers, which brought Ali Qapu Palace to the brink of destruction.

The first and second floors of Ali Qapu Palace were reserved for the palace staff and guards. This is evident from the simplicity and lack of ornamentation in the Diwan House, observatory, or guardhouse on the first floor. On the third floor, Ali Qapu’s architecture features large rooms through which the king could access the upper floors.

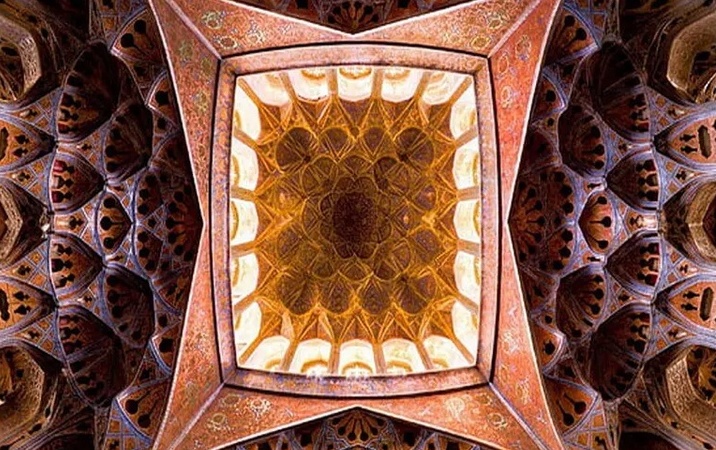

The wall decorations on this floor are from the ornamental designs of Shah Abbas II, with later additions by Shah Sultan Husayn. Two mezzanines are located above the Music Hall. The top and sixth floor of Ali Qapu Palace is famous as the Music Hall or Sound Room. This room was the gathering place for the king and royal musicians, who enjoyed immense pleasure while performing music.

Restoration of the building began in 2005 (1384 in the Iranian calendar) and continued until 2007 (1386). This restoration reinforced the balcony. The layers of dust accumulated over years of wars were cleaned, and the colors and various layers of the palace’s murals were repaired.

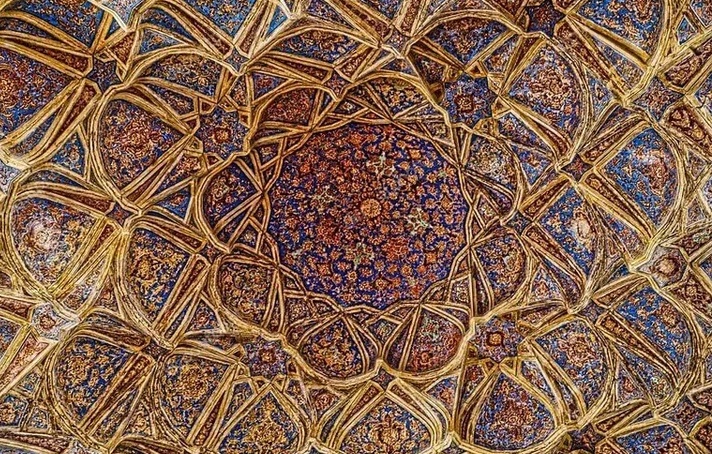

Although the paintings of Ali Qapu Palace have no precise date and it is unclear which artist created them, the exterior paintings of the palace, with their blue and yellow colors, are simply mesmerizing. Every corner is filled with beauty, and the murals and decorations of each floor never tire the viewer. Your gaze constantly rises to the ceiling to marvel at the paintings and the intricate small and large geometric shapes.

Even the royal staircases of Ali Qapu Palace are decorated with tiles in yellow and blue. As for the floral and foliate designs on the walls, alongside depictions of hunting scenes with animals and birds, bird motifs, Islimi and Khatai lines, and other layered decorative elements, they create a richness that makes one lose track of day and night.

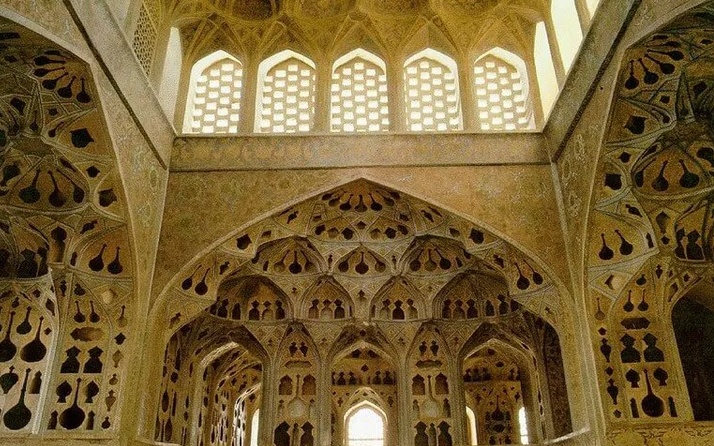

The art of stucco, with its simplicity, reached a golden era during the Safavid period. They used plaster, Isfahani plaster, white plaster, and “koshteh” plaster for stucco relief work, creating an extremely thin surface on the walls. This surface, with its very subtle relief, evoked the feeling of painting directly on the walls. Koshteh-bandi designs and decorative motifs appear abundantly on the walls of the Ālī Qāpū Palace.

If you go to the third floor and the Music Hall, you will encounter a special type of plasterwork called “tang-bandi,” where shapes resembling bottles and vases are carved into the walls.

In this type of Safavid decoration, various geometric shapes, including polygons and circular forms, are layered step by step on top of each other. This style of architecture can also be seen in some mosques and mausoleums. At Ālī Qāpū, this type of decoration under the ceiling of the Music Hall, alongside the tang-bandi on the walls, is truly spectacular.

One of the attractions of Ālī Qāpū’s architecture is the red-colored motifs and miniatures inside, which depict the art of that era on the walls of the lower hall of the palace. Reza Abbasi, one of the most famous and unparalleled artists of the Safavid period, was responsible for many of the palace’s miniature paintings, which is why his name has remained prominent to this day.

Ālī Qāpū Palace is one of the few palaces that was not satisfied with just one floor, or even two or three—it mesmerized everyone with six floors. In the past, there were two halls on the ground floor where the king’s administrative and court affairs were conducted, known as the “Sadrkhaneh” and the “Keshikkhaneh.” When viewed from the front, one might think they are looking at a two-story palace, but in reality, it has six floors.

With its Safavid and Qajar tilework and its 36-meter height, Ālī Qāpū was the tallest building of its time among the sights of Isfahan. Although the grandeur of the palace should not be compared to an ordinary building, it is roughly equivalent to an 8- or 9-story modern apartment.

After some time, multiple floors, verandas, decorations, and glasswork were added to enrich Ālī Qāpū. After all, it is the king’s palace, and its color and appearance had to be more magnificent than other houses. Overall, the construction of Ālī Qāpū took five stages, from the reign of Shah Abbas I in Isfahan to Shah Sultan Husayn.

From the very beginning, Ālī Qāpū included the entrance to royal buildings and the palace’s kitchen, the royal stables, the guards’ quarters, and the Safavid royal clinic. Through this entrance, one could access these areas from Naqsh-e Jahan Square.

However, not everyone could pass through—only the king and courtiers for administrative, ceremonial, or other matters unknown to the public. Even the king’s residence was accessed through this entrance, meaning approaching Ālī Qāpū required courage and a bit of recklessness.

A city cannot become grand and magnificent while the king’s palace remains unchanged. Especially when Isfahan became the capital of Iran, the king realized he had to assert his position to the people. The palace, which originally had two floors, was expanded with a third, fourth, half of a fifth floor, and a veranda, making the royal palace much more impressive—so much so that it resembled a large-scale palace.

It seemed that the architecture of Ālī Qāpū was not yet complete. This led to the addition of the Music Hall. By then, what more could the king want? Not just Naqsh-e Jahan Square, but all of Isfahan lay beneath his feet. He wanted such a large veranda solely to watch competitions and entertain guests. Next came a hall with peculiar niches and recessed plasterwork called tang-bandi, essentially giving him a concert hall as large as modern-day halls.

Perhaps even the grand veranda seemed small to the Great King of Iran. Whenever he sat there with his guests, he thought he needed to widen it to gain a broader view—from one side of the garden to the other—to watch polo matches, archery, and festivals.

Finally, a wooden ceiling with intricate knotwork was constructed along with 18 columns, which could be accessed via the royal staircases. In the center of this veranda, you can see a copper pool that supplied water to the other floors. An identical pool was symmetrically designed as a hollow and recess under the veranda ceiling, though I do not know the philosophy behind it. Once the Shah was assured that the architecture of Ali Qapu Palace was complete, he continued his kingship in full joy and satisfaction.

Such a palace, which in the early days was merely a gate between Naqsh-e Jahan Square and other royal buildings, today—with its many sections and decorations—is even more regal than many other palaces. The fame of Ali Qapu Palace is due to many things: its music hall, its copper pool, its decorations across various floors with the Tang-Bari, Koshte-Bari, and Muqarnas features.

I do not know about modern house entrances, but Ali Qapu had five entrances, one of which was solely for the officials of that time. This is why the entrance of Ali Qapu Palace was also called the Government Gate. Naqsh-e Jahan Square, which was just a garden at that time, was connected to Ali Qapu Palace, the Timurid Hall, the stable hall, and Chehel Sotoun Palace.

However, the other four entrances of Ali Qapu Palace—on four sides—namely the royal door, the harem door, and the Jebbeh-Khaneh or kitchen door, lagged behind.

The music hall, with nine rooms, one corridor, two spiral staircases, and four balconies, made Ali Qapu Palace culturally richer than before. The music hall was built on the top floors of Ali Qapu so that the leaders and kings could refresh their spirits with the music, alongside the blue beauty of the pool and the greenery of the square. While the raised decorations on the walls may have no purpose other than beauty, the decorations shaped like jars, amphorae, bottles, and chandeliers carved into the walls serve the purpose of reflecting sound inside the hall and the palace.

To reach the music hall of Ali Qapu Palace, one must pass through spiral staircases filled with decorative paintings. When musicians played, the sound of their instruments hit the holes in the walls, reminiscent of the setar, preventing it from reaching even six floors away. The recesses under the ceiling of the room also naturally return the sound. The stucco work of the hall closely resembles that of the Ardabil Chinese House Museum.

The veranda of Ali Qapu Palace on the third floor reaches up to the fifth floor in height. Initially, there was no ceiling, but later Shah Abbas II built this veranda with 18 wooden columns adorned with beautiful mirrorwork. Under its shade, people would watch various ceremonies and polo matches, while behind the veranda their eyes could reach toward the Toheed Dome.

Behind the Music Hall and in the veranda of the Ali Qapu Palace, there is a marble and copper pool right in the center of the palace hall, decorated with marble stones, where the water would constantly fill and empty with the air. Now, how they used to get water up to the third floor is a story in itself. In the past, fountains were placed right in the middle of it, which today seem to have disappeared.

If you have seen the two colorful and ornate mosques in front of Ali Qapu in Isfahan, I imagine you might have overlooked the small, earthy dome behind this building. Perhaps it is because the king’s palace is right behind it. Of course, although there are disputes about its construction and founding date, that is no reason to ignore it.

The Towhidkhaneh (Monotheism Chamber) of Ali Qapu Palace, with its fresh clay-brick texture and brick exterior, and its semi-circular arch, captures your heart in a way that seems only Europeans could inspire such adaptations in the minds of Qajar kings. An inscription in Thuluth script is also embedded on the wall inside the twelve-sided dome chamber, though no one knows anything about the history of the inscription or its author.

It is said that Shah Abbas the Great, also known as Shah Abbas I, may have wanted to show his respect to the two mosques in front of him by constructing this dome atop Ali Qapu Palace. In any case, one of its uses was that Sufis of the Safavid era would gather there, and since the king was busy and could not attend to them, he would assign the responsibility of guiding the Sufis to someone titled the Khalifeh-ol-Khalefe, to instruct and lead the Sufis and spiritual seekers.

During the Safavid period, no one could act arrogantly or enter this sacred space in Ali Qapu Palace with weapons. As usual, the Qajars came and did what they should not have done, and they considered ways to diminish the sacredness and security of the Towhidkhaneh.

During the Pahlavi era, the roof of the Towhidkhaneh of Ali Qapu Palace was covered, and they built prisons and buildings under the title of Shahrbani—today’s police force—on parts of its grounds. Today, this building is neither a prison nor houses the police; however, after restoration and repair, it is now purely a site to admire.

There are three staircases in Ali Qapu Palace in Isfahan, two of which were built as symmetrical spiral staircases with 114 steps, serving as passages for the palace guards. Another staircase, known as the Royal Staircase, was designed with stepped, straight tile work, with each step ranging from 22 to 32 centimeters in height—enough to take your breath away.

Members of the court used this staircase to reach the upper floors and behold the king’s presence. Since the reception hall on the third floor could not accommodate many guests, three stations were built along the Royal Staircase, from the ground floor to the reception hall, where guests would wait until the king granted them permission to enter. The floor of this royal staircase is decorated with blue and yellow tiles, while the walls are adorned with intricate drapery-like decorations.

There are three reasons behind the naming of Ali Qapu. The first was to demonstrate the power of the Safavid dynasty against the Ottoman Empire, where the Ottomans had constructed a similar palace called Bab-ı Ali in Istanbul. Shah Abbas I, wanting to showcase the enduring grandeur and superiority of the Iranians, built Ali Qapu Palace even more magnificent and ornate than its Ottoman counterpart.

The second reason was Shah Abbas I’s special devotion to Imam Ali (peace be upon him), which led him to install a silver ornament for the shrine of Imam Ali (peace be upon him) and bring one of the doors of the Imam’s shrine entrance as a blessing to add to the main entrance of Ali Qapu. Shah Abbas I respected this door to such an extent that whenever he passed by it on horseback, he would dismount and enter his palace with reverence because of his spiritual closeness to the Imam.

The third reason is that before transferring the capital to Isfahan, the Safavids ruled from Ali Qapu Palace in Qazvin. Later, when the capital was moved from Qazvin to Isfahan and Naqsh-e Jahan Square, they named the entrance of the square “Ali Qapu” as a continuation of their legacy. The name Ali Qapu is derived from Turkish, meaning “Great Gate” or “Grand Portal.” This name is fitting: upon entering, one immediately finds themselves in the heart of the world and Naqsh-e Jahan Square. The palace is also known as Dowlat Khaneh-ye Mobarak-e Naqsh-e Jahan or Qasr-e Dowlat Khaneh.

Despite its grandeur, the palace does not always get overcrowded. When the opportunity arises, it can hold a miniature version of the “Half of the World” within itself. Keep in mind its peak hours, and visit daily from 9:00 AM to 6:00 PM, except on 14th and 15th of Khordad, the 21st of Ramadan, the 28th of Safar, and on Tasua and Ashura. Summers are scorching, and winters are bone-chilling, but spring and autumn at Ali Qapu Palace will give you truly unforgettable days.