SAEDNEWS: A massive hall dating back to the Bronze Age has been uncovered in excavations near the royal Sedin tomb northwest of Berlin.

![Discovery of a 3,000-Year-Old Hall Belonging to a Legendary King in Germany [Photo]](https://en.saednews.com/storage/files/post/e145410f-17aa-4f5b-842a-87973626121b-Kkmt4wgZI3SYWVfq/image.jpg)

According to Saed News’ society desk, archaeologists believe the newly unearthed remains of a massive Bronze Age structure may be the assembly hall of a legendary king known as “Heinz,” a mythical figure said to have been buried in a golden coffin.

Since spring, the State Office for the Preservation of Historical Monuments, in collaboration with archaeologists from the University of Göttingen, has been conducting extensive excavations around the Sedin royal cemetery.

The royal graves of Sedin and Groß Pankow are considered the most important ninth-century BCE burial complexes in Central Northern Europe. They were originally uncovered in 1899 during stone extraction work.

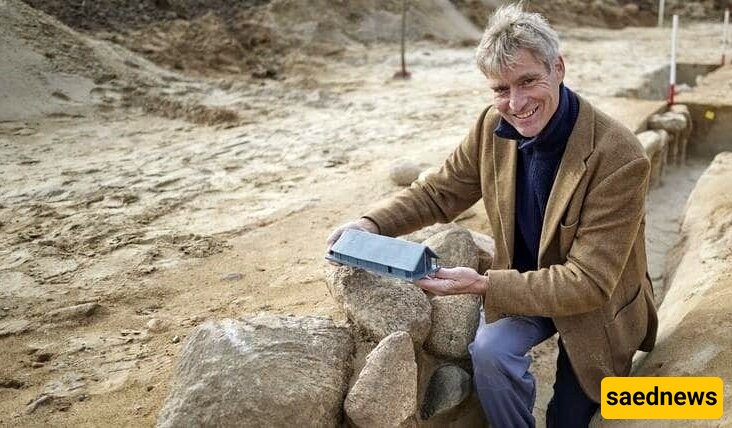

As the State Office for the Preservation of Historical Monuments announced Wednesday in Wunsdorf, this newly discovered structure is the largest of its kind from the Nordic Bronze Age (roughly 2200–800 BCE). Experts believe it may have been the assembly hall of the legendary King Heinz, measuring 31 by 10 meters. “This is a truly significant and remarkable find,” said State archaeologist Franz Schopper.

Dr. Immo Heske, a leading archaeologist at the University of Göttingen, explains: “Prehistoric houses were usually six to seven, occasionally eight meters wide. But this structure is ten meters across—highly unusual.”

The building’s walls were made of wooden planks and wattle-and-daub, coated with clay plaster, and the roof was likely covered with thatch. With an estimated height of seven meters, scholars assume there were additional floors for living space and storage. A central fireplace was located in the western half of the hall, and a miniature vessel discovered in the north wall is thought to have been a ritual offering.

Experts also uncovered two exterior walls made from fieldstones—a highly atypical construction technique for Northern Europe during the Bronze Age.

Heske notes that the builder or occupant of the hall likely drew inspiration from travels: “If you consider European networks of the time, it’s conceivable that he saw stone construction techniques during journeys to the south.”

Dating the hall between the 9th and 10th centuries BCE—around 3,000 years ago—Heske suggests it was probably a ruler’s residence. “Between 1800 and 800 BCE, only two other buildings of this kind existed between Denmark and southern Germany,” he says.

Given its size, archaeologists are confident that no ordinary farmer could have lived in this hall, which was designed for large gatherings and celebrations. Its construction likely relates to the legendary King Heinz, believed to have been buried in a royal grave just meters away.

Franz Schopper of Brandenburg’s State Archaeology Department adds: “It’s very likely a king lived here and held meetings and consultations in this hall. Perhaps the ancestors of King Heinz lived here. What’s clear is that this hall dates back to the 9th and 10th centuries BCE and was in use for at least 80 years.”

Tobias Dannau, Brandenburg’s Minister of Science, sees the find as a key piece in understanding Bronze Age life: “We now have the opportunity to gain insights into living conditions, culture, house construction, and burial practices of the period.”

The entrance to the 3,000-year-old royal tomb lies near the hall’s excavation site. Documentation of the building and its plans will continue through the end of the week, after which the site will be reburied. Excavations are far from over, however.

The site may be reopened in coming decades to allow new technologies or specialized DNA analyses to uncover deeper details about the people who lived near the Sedin royal cemetery. Over the next two years, the University of Göttingen and the State Office for the Preservation of Historical Monuments plan further extensive excavations around the royal tomb as part of this project.