SAEDNEWS: Nowruz has many traditions, among which Chaharshanbe Suri is included, and each province has its own customs for this day.

According to SAEDNEWS, Chaharshanbe Suri is one of the most important Iranian festivals, also known as Red Wednesday or the Last Wednesday of the Year. It takes place on the final Wednesday evening before Nowruz, the Persian New Year, and can be considered one of the first celebrations of the Nowruz season.

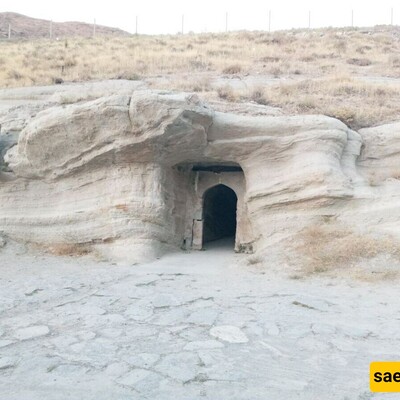

As the New Year approaches, everyone prepares to welcome it, and the first celebration of Nowruz, Chaharshanbe Suri, is organized. This joyful festival is deeply rooted in Iran’s ancient traditions. On this day, people gather wood and bushes, pile them together, and light a fire in the courtyard or alley at sunset.

After the bonfire, family members gather together and roast the last stored seeds and nuts of winter—such as pistachios, watermelon seeds, pumpkin seeds, almonds, chickpeas, wheat, hazelnuts, and hemp—over the sacred fire, sprinkling them with salt for blessing. Ancestors believed that anyone who eats this mixture becomes kinder, friendlier, and more free from resentment compared to others.

Young women or girls who hope for marriage or dream of a pilgrimage make a wish on Wednesday evening and leave their homes. They quietly listen to the conversations of passersby and interpret their words as omens, both good and bad, sweet or bitter. If they hear pleasant words, they believe their wishes will come true; if bitter words, they worry their hopes for the new year may not be fulfilled.

One of the most common Chaharshanbe Suri customs is jumping over the fire. Despite its centuries-old origin, this tradition has survived intact, unlike many other old customs that have faded over time.

After lighting the fire, people take old pots to the rooftop. They place salt (representing misfortune), charcoal (representing bad luck), and a small coin inside the pot. Each family member spins it around their head, and the last person throws it from the roof into the street while whispering, “I have thrown the house’s troubles into the alley,” symbolically removing misfortune from the home.

Those who feel their fate is “tied” tie a corner of a handkerchief or piece of cloth and stand along a path. When the first passerby arrives, they ask them to untie the knot, believing it will release their blocked destiny.

Women and girls with wishes carry a bowl and a copper spoon to knock on the doors of seven houses in succession without speaking. The homeowners, aware of the tradition, place coins, rice, sweets, or nuts into the bowls. If the participants fail to receive anything, they believe their wish may not come true. Sometimes young men playfully imitate this tradition for fun.

After pot breaking, bonfires, fortune-telling, untying knots, and spoon tapping, young people participate in “shal andazi.” They tie several silk or chiffon scarves to a three-meter-long rope, toss it from a rooftop or stairs into a home through a chimney or window, and signal the homeowner with a cough. The homeowner, expecting the scarves, places a prepared gift inside the scarf and pulls it up, completing the ritual.

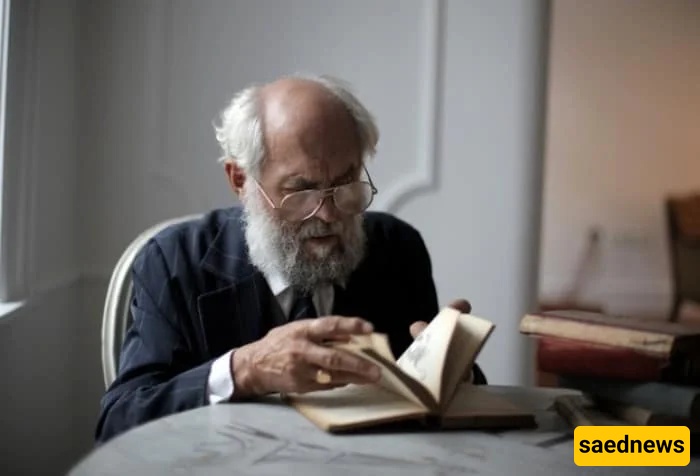

Storytelling and reading the Shahnameh (Persian epic) is another enduring tradition. Typically, an elder of the family narrates stories on Wednesday evening. If someone in the family plays a musical instrument, they perform, and poems celebrating spring and the new year are recited. This custom is so cherished that it is also practiced during Yalda Night.

Qelya Soodan is a method to ward off evil spells. According to tradition, dry potash is ground in a small rice mortar by seven young girls, mixed with water, and then sprinkled around the house believed to be bewitched, neutralizing magic.

For enhancing luck, some collect water from a tannery, bring it home, and sprinkle it over themselves to open their fortune for the year.

In households with illness, women prepare a special porridge called Ash-e Bimar or “Imam Zain al-Abidin’s Porridge” to heal the sick before the new year. They knock on neighbors’ doors anonymously, asking them to contribute ingredients like flour, grains, rice, or onions to the porridge. If unavailable, coins are left, which are used to buy ingredients. Any leftover porridge is given to the needy. This dish is believed to cure any ailment.

A unique custom involves women visiting apothecaries to buy incense (kondor) and fragrant substances (khoshbu). After acquiring them through a playful ritual involving running away as the shopkeeper offers the items, they burn the incense at home to remove obstacles and protect against the evil eye.