Step through the carved doors of Moshir Mosque and you’ll find dazzling tilework, spiral stone columns and a centuries-old clock that once kept Shiraz on time.

Whenever I open history books and reach the Qajar era, I often read complaints about incompetent rulers — yet many beautiful historic works also date from their time. While researching Moshir Mosque today I came across the name Mirza Abu al-Hasan Khan Moshir al-Molk, who apparently built this beautiful mosque between 1265 and 1274 AH. Mirza Abu al-Hasan built the mosque in the old neighbourhood known as Sang-e Siah beside the Armenian bazaar, so the merchants there could also visit. Read on to see how much interesting detail I’ve collected and how lovely this mosque truly is.

If you haven’t yet visited Shiraz, don’t delay: alongside Shiraz’s incredible scenery and historic buildings, this detailed guide from Alibaba Travel Magazine should put Moshir Mosque on your must-see list.

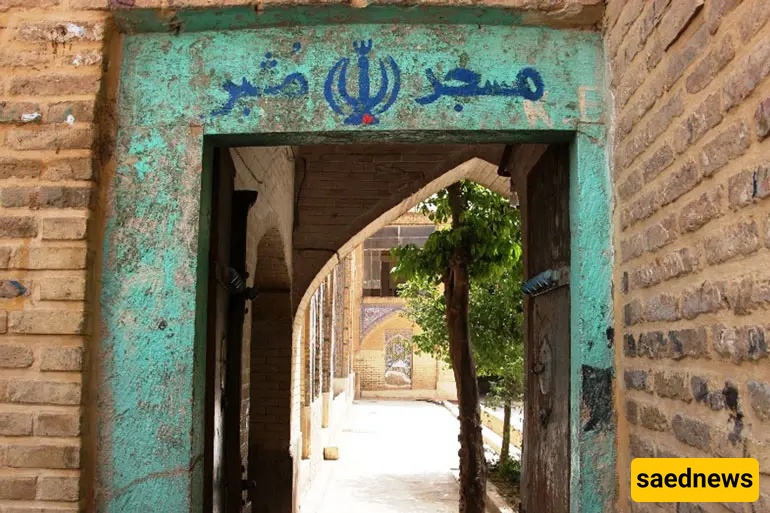

Moshir Mosque is a Qajar-era architectural masterpiece in Shiraz. It stands on North Gha’ani Street near the Armenian bazaar and the Armenian quarter. Mirza Abu al-Hasan Khan Moshir al-Molk — who served as a minister — commissioned the structure between 1227 and 1236 in the Iranian calendar, and it is now one of Shiraz’s notable attractions.

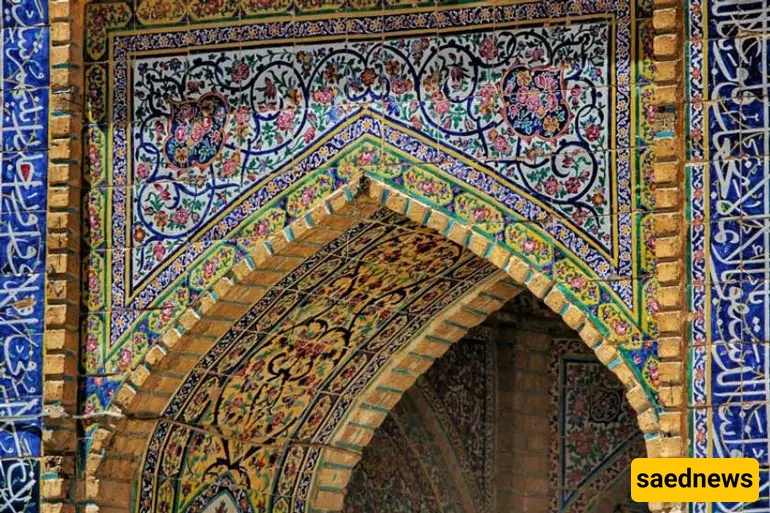

The mosque’s architecture arrestingly showcases authentic Iranian–Islamic design. Experts note that for solidity, courtyard pool and carved stone columns, Moshir Mosque is unrivalled after Vakil Mosque.

Moshir Mosque sits in the historic Sang-e Siah quarter, one of the city’s old neighbourhoods that dates back to Karim Khan Zand’s era. At the time, neighbourhoods were smaller and city walls tighter; Sang-e Siah then also included the Darvazeh Kazerun area. The neighbourhood hosts many historic sites: the tomb of Bibi Dokhtaran, Ilkhani Mosque, Ilkhani Bath, the Armenian bazaar, Sang-e Siah Church, the Kurdish Hosseiniyeh, Forougholmolk House, Saadat House, Rezaian House, Haj Zainal bazaarlet and the shrine of Seyyed Taj al-Din Gharib. The quarter’s name — “Sang-e Siah” (black stone) — reportedly comes from the grave of the scholar ‘Omar ibn ‘Uman (known as Sibawayh), which bore a completely black stone.

The mosque building contains several prayer halls and two-storey cells that once housed theological students. As noted in the book Shiraz Delnavaz, beyond this mosque Mirza Moshir al-Molk also built a grand Hosseiniyeh and endowed part of his assets to the Ahl al-Bayt.

A special charm of Moshir Mosque is the display of Qajar-era vessels kept around the site. These items were reportedly used during mourning rituals in Muharram and Safar and give visitors a vivid sense of the mosque’s ceremonial life.

In terms of workmanship — carved stone columns, decorative detail and its prayer halls — Moshir is among Shiraz’s most beautiful mosques after Vakil. On 25 Ordibehesht 1351 (Iranian calendar) it was registered as one of Iran’s national monuments under registration number 911.

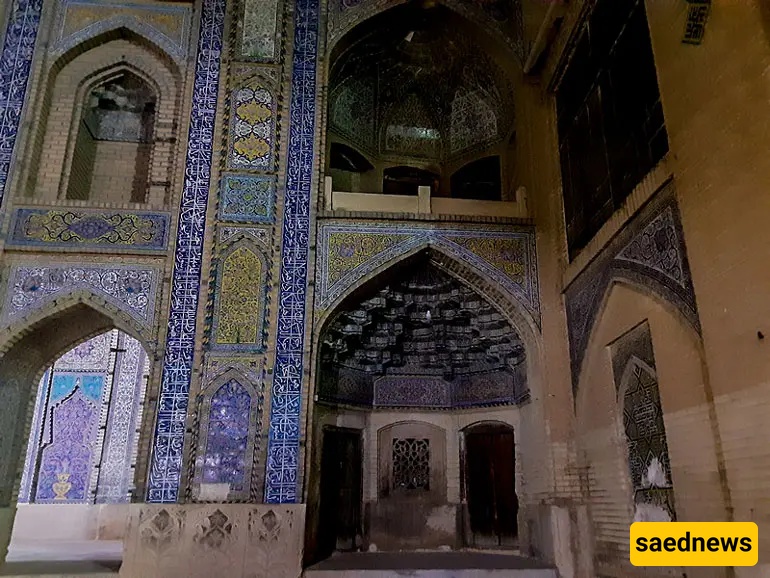

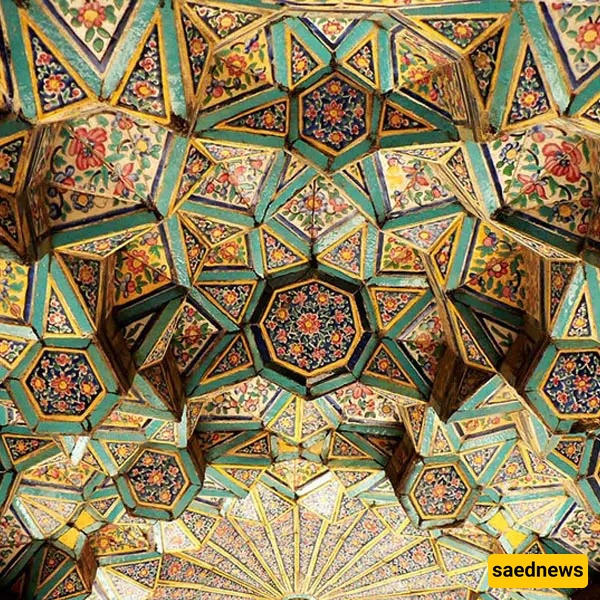

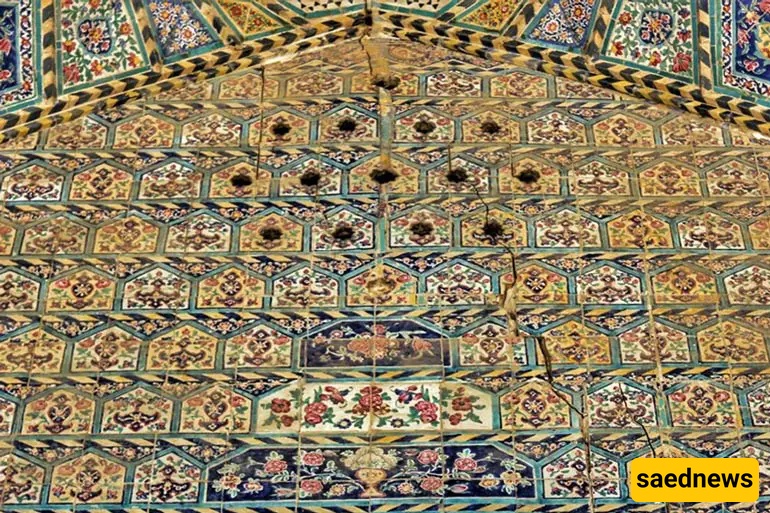

Every corner of Moshir Mosque enchants, but notably the small northern prayer hall and its colourful tiles and muqarnas offer visitors the greatest visual delight. Above that hall rise two minarets with exquisite tilework, enhancing the mosque’s dignity.

The mosque’s design is so striking that it draws both domestic and foreign tourists eager to see its fine detail.

The mosque’s main eastern entrance — which used to open toward the Armenian bazaar — connects to a special octagonal vestibule (hashti) that overlooks the courtyard and divides the route toward two directions.

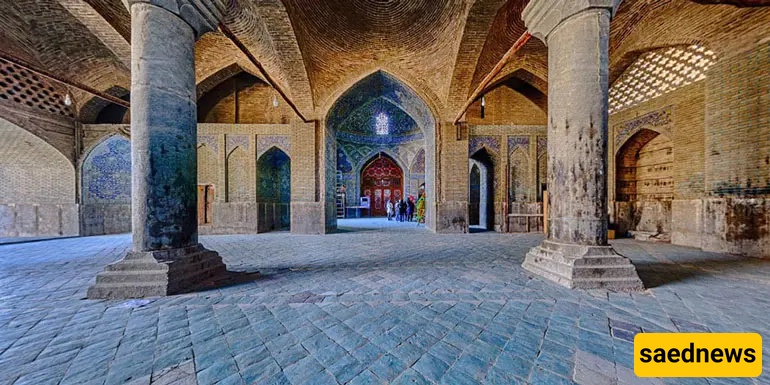

The right path leads to the courtyard, toilets, the men’s teahouse and the men’s staircase; the left path leads to toilets, the women’s teahouse and the women’s staircase. The internal entrance reveals spiral-carved stone columns that astonish on arrival.

After entering through the door you can view the courtyard, whose central rectangular pool measures 25 by 10 metres and is carved from a single stone block; in the past it was filled with charitable water.

The mosque’s mihrab is exquisitely tiled and contains a marble panel inscribed with Sura al-Tawhid in Naskh script. This section is among the mosque’s most spiritual and visually striking features.

On the mosque’s north side is a small shabestan decorated with patterned colored tiles; two northern vaults feature muqarnas tilework. The shabestan’s front bears a high niche with large Qur’anic verses in superb Thuluth script; above this shabestan stand two beautifully tiled minarets.

The northern shabestan — also called maqsurah — rests on four stone columns. To the south of this shabestan is a tiled mihrab and, centrally, a large deep well whose coolness used to temper the space in summer.

On the mosque’s eastern side there is a high decorated niche with muqarnas and a Thuluth inscription; behind that niche a long corridor and a large door lead out toward the Armenian bazaar.

Overall, the mosque contains three shabestans for different seasons:

The western shabestan is a summer hall; on its east side sits a large, beautiful iwan that shields it from sun. Its double-layered ceiling prevents midday sun, and the western wall’s double structure reduces evening sunlight.

The southern shabestan is for spring, with many doors and windows; its ceiling includes openings designed for cooling.

The northern shabestan is the winter hall; on very cold days a few coal braziers would warm it. This winter hall has no windows and only two small doors at the corridor’s end. Its floor is 60 cm higher than the main mosque floor, a design that helped retain heat. Several smoke vents in the ceiling allowed brazier smoke to escape, but because of the tall northern iwan there is typically no noticeable draft facing it.

Several staircases lead to the mosque’s second floor and roof. On the second floor — built only on the mosque’s north and east (and southern side) — rooms connect to one another.

The women’s and men’s royal platforms feature skylights in their ceilings: glass panels 50–80 cm above the roof floor that admit daylight.

The men’s teahouse is on the right upon entry and the women’s teahouse on the left. These spaces served guests, especially during Muharram and Safar gatherings.

The mosque’s northern, eastern and western courtyards contain elegant and inventive iwans. The northern iwan — called the four-bow vault — is a peak of Iranian–Islamic architecture with tilework, muqarnas, inscriptions and a stone dado; above it stand two famous minarets and the historic clock.

At the northern iwan’s facade a Thuluth inscription bears the date 1270 AH. Its muqarnas also served a warming function for the winter shabestan. The northern iwan is also known as the pearl vault.

Adjoining it, the eastern iwan mirrors similar tile and muqarnas work and links via a corridor to the outside. The western iwan, in addition to decorative work, backs a large shabestan whose vault and dome rest on ten single-piece carved stone columns; those columns are spirally fluted.

Historic doors and inscriptions appear on the southern side of the western iwan: an inscription reads that, by order of Moshir al-Molk, the dedication was made by the servant Jani Ali Askar al-Arsanjani in 1289 AH.

Various staircases lead to the second floor royal platforms and then to the roof. The skylights above those rooms provide unique lighting and beauty.

The mosque clock — a major part of Moshir Mosque’s fame — was the first clock to come to Shiraz. It was made in England and chimed every 15 minutes, striking the quarter and the hour; the hourly chimes once served as a public time signal for much of the city. The clock face was visible from both the mosque’s west and east.

Originally the clock’s numerals were Western (Latin), but Mirza Abu al-Hasan Moshir al-Molk insisted on Persian numerals and had them replaced — a detail that made the clock even more unique.

This over-170-year-old clock is decorated with tiles and inlay and is one of Shiraz’s oldest public clocks. During the Qajar era only two clocks were installed on prominent buildings: Moshir Mosque’s and the clock at Shah Cheragh shrine.

No wonder the mosque clock has become one of Shiraz’s notable sights, narrating a long history in a single chime.

The best time to visit Shiraz — and thus Moshir Mosque — is spring, when the scent of orange blossoms fills the air. May (Ordibehesht) is particularly recommended since you can comfortably visit the spring shabestan and enjoy the mosque at its most fragrant.

The mosque is open daily from 09:00 to 17:00 and a typical visit lasts around one hour.

Moshir Mosque is located in Fars Province, Shiraz, Sang-e Siah neighbourhood, Gha’ani Street, Darband Moshir quarter, adjacent to the Armenian bazaar.

You can also reach Moshir Mosque via Shiraz metro map.

It’s impossible to visit Shiraz without including Moshir Mosque among your essentials — once famed for the English clock over its iwan, a cutting-edge technology of its day, it now stands as a historic novelty.

But beyond the foreign-made clock and its Persian numerals, the mosque’s interior decoration and architectural detail speak for themselves: you don’t need to be an architect to be stunned by its ceilings, arches and walls.

Moshir Mosque, along with Nasir al-Mulk Mosque and Shah Cheragh shrine, offers visitors a genuine route to understand Iranian–Islamic architecture — all while breathing Shiraz’s orange-scented air and discovering its many secrets.

[Image omitted — original included photos of tilework, columns, the courtyard pool and the mosque’s clock.]

Tip | |

|---|---|

Best season | Spring (especially May/Ordibehesht) for orange blossom scent and access to the spring shabestan. |

Visiting hours | Open daily 09:00–17:00; typical visit ~1 hour. |

Location | Sang-e Siah neighbourhood, Gha’ani Street, next to the Armenian bazaar — use Shiraz metro or local directions. |

Must-see features | Spiral-carved stone columns, tiled mihrab with Naskh inscription, northern shabestan and the historic English clock with Persian numerals. |

Accessibility tip | Entrance historically opened toward the Armenian bazaar via an octagonal vestibule; expect stair access to second-floor royal platforms and roof. |