SAEDNEWS: The Eurasian common shrew (Sorex araneus), whose lifespan rarely exceeds a year, has no desire to waste its precious months of life enduring the winter cold and the first snowfall.

According to Saed News’ science desk, in animals like bears, it’s not unusual to bulk up before winter. By slowing their metabolism, they endure seasonal leanness. But now researchers are talking about another creature that takes an even stranger approach to facing the cold.

Eurasian common shrews (Sorex araneus), whose lifespans rarely exceed a year, are not willing to waste precious months of their lives in the winter chill or under falling snow.

Instead, these tiny mammals employ a radically different survival strategy. By shrinking their feeding organs, they conserve the small energy reserves they have.

This clever adaptation is known as the “Dehnel phenomenon,” named after Polish zoologist August Dehnel. It allows shrews weighing just 5 to 12 grams to reduce their body weight by up to 18 percent in response to falling temperatures.

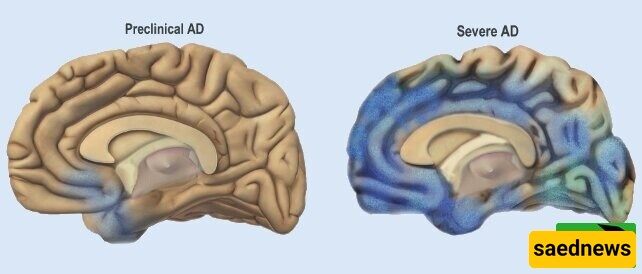

The change is dramatic, causing more than a quarter of the shrew’s brain mass to shrink. The purpose? To regrow the lost tissue in spring.

Now, researchers from the United States, Germany, and Denmark have identified several genes responsible for this phenomenon and found intriguing parallels with genetic changes in humans linked to diseases, including Alzheimer’s.

These findings come just a year after the same team cataloged metabolic changes in the liver, cerebral cortex, and hippocampus associated with seasonal shrinkage. They suggest that understanding these processes could inform treatments for human neurological disorders.

In a follow-up study, the team compared gene activity in the hypothalamus of shrews with that of 15 other mammal species. The hypothalamus plays a key role in regulating metabolism and adapts animals’ activity to seasonal changes—making it a prime target for study.

Using extensive datasets, the researchers identified hundreds of genes active in shrews that also had counterparts in the brains of other mammals, including rodents and insectivores.

William Thomas, an evolutionary biologist at Stony Brook University and a senior scientist on the study, explained:

"We generated a unique dataset that allowed us to compare the hypothalamus across species and seasons. We found genes that adjust energy homeostasis with the seasons and others involved in cell death, likely linked to seasonal brain shrinkage."

Shrews’ seasonal genes include several that control calcium signaling at the blood-brain barrier, facilitating rapid environmental responses. One standout sequence, BCL2L1, appears critical for managing the breakdown of individual neurons.

By comparing RNA transcripts in cell cultures from domestic rat brains, the team confirmed these mechanisms, revealing a complex web of signaling and cell death that enables the brain to shrink and regrow seasonally.

Among the five genes deemed most important for the evolution of the Dehnel phenomenon are genes that recycle membrane proteins, mediate synaptic membrane function, and even ones linked to obesity and Alzheimer’s in humans.

Given the shrews’ short lifespan, sacrificing neurons to conserve rapidly depleting energy stores is effective. In humans, however, similar changes would be catastrophic.

Modern medical research increasingly links metabolic dysfunction to neurodegenerative disease. Studying how shrews deliberately shrink their brains could offer profound insights into diagnosing and treating cognitive decline.