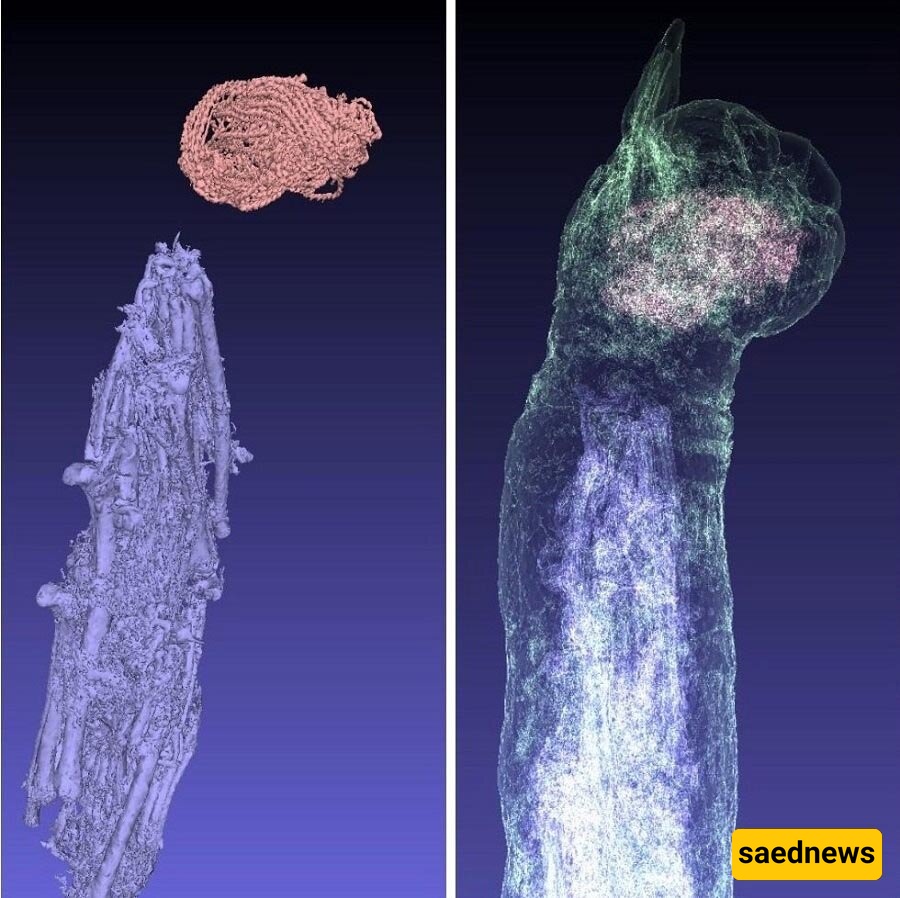

SAEDNEWS: A 3D scan of a cat mummy shows the presence of three tails and five legs wrapped within the mummy’s linen. Researchers have proposed various explanations for this unusual discovery.

In 2017, French scientists scanning a 2,500-year-old mummy expected to see the skeleton of a single ancient Egyptian cat—but instead, they discovered the images of multiple cats. Since feline biology has changed little since the 5th century BCE, the presence of a cat with three tails and five legs seemed extraordinary.

The mummy is housed in the city museum of Rennes, France. Researchers from the French National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) used CT scans to examine its contents without unwrapping it and then reconstructed the skeleton in 3D.

INRAP researcher Théophane Nicolas, who participated in the reconstruction, said, “Some scholars suggest this could be an ancient hoax orchestrated by unscrupulous priests—meaning that instead of mummifying a single cat, they placed parts of several cats together in one coffin.”

Selimah Ekram, an Egyptology professor at the American University in Cairo, notes that while a five-legged, three-tailed cat might seem bizarre, it is likely a “composite” mummy—and not as unusual as it appears. “With mummies, the packaging doesn’t always reflect what’s inside. We have several explanations for this phenomenon.”

Archaeologists studying mummified cats and cat remains from multiple tombs in the Bubasteum temple in Saqqara, Egypt—the primary feline burial site—identified 184 cat mummies and 11 packages containing large amounts of cat bones. Some of these packages contained the remains of two to six cats, distinguishable by their relatively large size.

Regarding the Rennes mummy, Ekram offers several theories. One is that it could be the work of priests defrauding buyers of cat mummies, since the contents did not match their external appearance.

A second theory ties to the Egyptian concept of “part-for-whole,” where part of something symbolizes the whole, and proper rituals could turn incomplete bones into a complete cat in the afterlife.

A third possibility is that these cats had died near a sacred site and were mummified together as sacred beings.

Ekram also notes that sometimes an incomplete skeleton is simply the result of human clumsiness: “When mummifying something, parts can easily fall off.”

The Rennes mummy offers a clue that may solve the puzzle. Nicolas noted in an email that its dried flesh and bones had decayed before mummification, with holes made by carrion insects.

Given this, Ekram leans toward her third theory: the cats likely died near a tomb, were collected during decomposition, and then mummified. “For this particular mummy, they gathered pieces of deceased animals in a sacred space to bring them joy in the afterlife,” she says.

In recent years, animal mummies have been studied far more extensively than human mummies, thanks to their smaller size, which makes them easier to scan. Each new scan continues to reveal surprises. Two-thirds of the cat mummies collected from the Bubasteum show evidence of violent death, suggesting that priests often raised cats for sacrifice before mummification.

Ekram is skeptical of the fraud theory. As noted by Zivie and Lichtenberg in Divine Creatures, priests may not have intended to deceive visitors with partial skeletons; rather, high demand for cat mummies combined with limited supply likely dictated these composite arrangements. In the end, what truly matters may not be what’s inside the mummy.