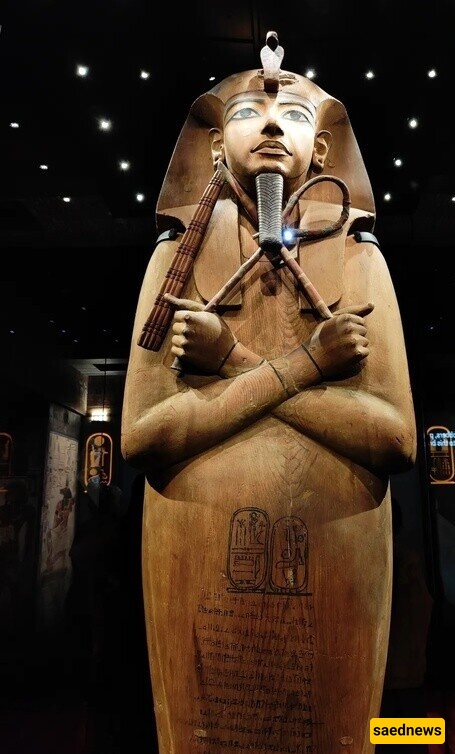

SAEDNEWS: This sarcophagus originally held the body of Pharaoh Ramses II around 3,200 years ago. But 200 years later, when the pharaoh’s remains were moved elsewhere, the sarcophagus came to house the body of a high-ranking priest instead.

According to Saed News’ Society Service, citing Faradeed, a recent study by an Egyptologist has concluded that a previously overlooked section of a granite coffin actually once held the body of one of Egypt’s most famous pharaohs.

The granite fragment, recently identified as part of the stone coffin of Ramses II, measures more than five and a half feet long and three inches thick, forming nearly an entire side of the coffin.

Ramses II, who ruled during the 13th century BCE, is among the best-known rulers of ancient Egypt. This 19th-dynasty king expanded Egypt’s territory as far as modern-day Syria, fathered roughly 100 children, and possessed one of the civilization’s most lavish coffins.

Yet the carved granite coffin designed to hold that golden coffin had remained unidentified—until now.

Frédéric Pierroux, an Egyptologist at the University of Paris-Sorbonne, recently reexamined a coffin fragment discovered in 2009 at the ancient cemetery of Abydos. At the time, experts from France’s National Center for Scientific Research speculated that the intricately carved stone box had contained the remains of two different individuals from different periods.

The second occupant of the stone coffin was a high priest named Menkheperre, who lived around 1000 BCE. Identifying the first occupant proved more challenging: archaeologists knew only that he was a prominent figure from Egypt’s New Kingdom period.

When Pierroux studied the inscriptions on the coffin fragment, he realized that the hieroglyphs bore Ramses’ name. The inscriptions included an oval-shaped symbol, typically used alongside royal names, which had previously been misidentified and misinterpreted.

Ramses’ reign lasted roughly 67 years, making it one of the longest in ancient Egyptian history. Known as the “Builder Pharaoh,” he commissioned numerous temples across the region. As Pierroux notes, it is rare to find an ancient Egyptian site without Ramses’ name, which he even added to buildings constructed before his reign.

Ramses died in 1213 BCE and was buried in a gilded wooden coffin placed inside a stone coffin, which itself rested within a larger granite coffin. Later, the wooden coffin was stolen, the stone coffin was broken apart by looters, and the granite coffin—of which this fragment remains—was reused by Menkheperre.

Pierroux explains that during Egypt’s 19th dynasty, the Valley of the Kings endured repeated plundering amid economic and social crises that led to resource shortages. Even royal family members were sometimes forced to repurpose funerary objects crafted for their predecessors.

The mummy and coffin of Ramses were rediscovered in 1881 at a hidden location within the Deir el-Bahari temple complex, alongside the remains of 50 other nobles, including Ramses’ father, Seti I. Since then, Ramses’ golden coffin and mummy have been displayed in museums worldwide. Whether this granite fragment, currently held in Abydos, will ever be exhibited remains uncertain.