SAEDNEWS: As Iran navigates the treacherous currents of internal discontent and external confrontation, a senior media official’s polemic against secular nationalism has opened a revealing window into the Islamic Republic’s ongoing identity crisis.

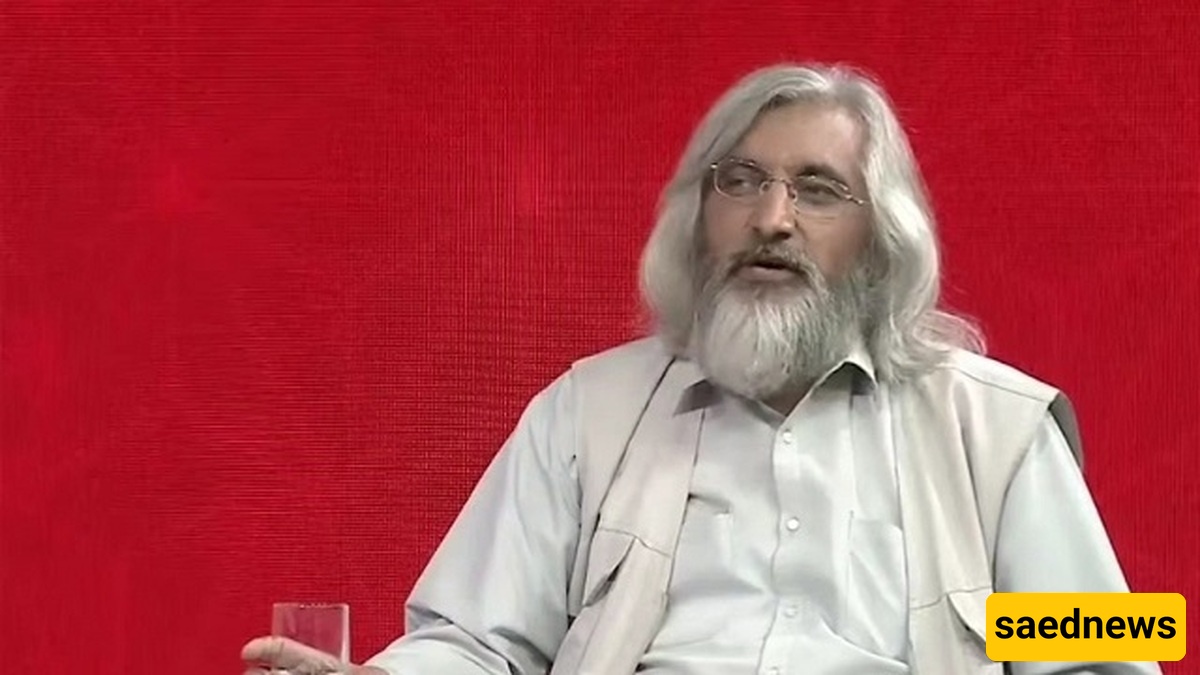

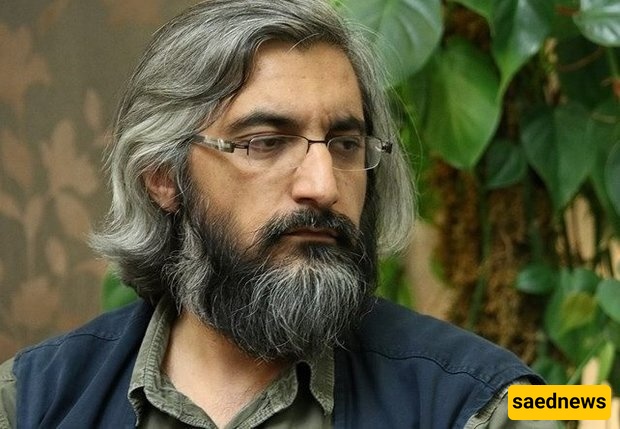

According to Saed News, recent remarks by Vahid Jalili—deputy head of Iran’s state broadcaster (IRIB), ideological architect of the hardline Paydari Front, and brother of the conservative presidential candidate Saeed Jalili—have reignited an enduring debate over the meaning of “homeland” in the Islamic Republic. Speaking on Ofogh TV, a network known for its staunch ideological programming, Mr. Jalili condemned what he perceives as a growing tendency to define national solidarity purely in geographical or secular terms. “Some wish to speak only of the homeland and omit God and the Prophet,” he declared, adding that Iran should not be reduced to “a pen,” implying a lifeless, utilitarian space devoid of spiritual character.

Though ostensibly aimed at unnamed voices within the media and political sphere, Mr. Jalili’s comments are widely interpreted as a reaction to the wave of nationalist sentiment that swept through Iranian society during the recent 12-day military confrontation with Israel—a mood that, temporarily at least, eclipsed the clerical establishment’s preferred narrative of pan-Islamic unity.

The backlash has been swift and multi-faceted. Observers have pointed to the IRIB’s own heavy reliance on patriotic imagery, rhetoric, and even pop music—most notably a wartime anthem by Mohsen Chavoshi—as evidence of a convenient ideological flexibility. If nationalism is indeed such a corrupting influence, they ask, why did the state so willingly co-opt it when under pressure?

Mr. Jalili’s intervention has also drawn attention to broader contradictions in the regime’s approach to religion and nationhood. Critics recall that the very television network he now helps direct was once run by the son-in-law of Morteza Motahhari, the cleric-philosopher whose seminal work The Mutual Services of Islam and Iran sought to reconcile the two traditions. “Why position Iran and Islam as opposites?” one critic asks. “Iran is not devoid of spirituality; it is a vessel for it.”

Such criticisms are not merely academic. They reflect deeper anxieties about the direction of state ideology, particularly in the aftermath of a deeply divisive election cycle. Last year’s presidential and municipal elections were marked by low turnout and broad voter apathy. Even among those who participated, the majority rejected the hardline agenda associated with the Jalili brothers. In this context, Mr. Jalili’s attempt to impose a narrower ideological framework on national identity appears tone-deaf, if not outright alienating.

The invocation of “God and the Prophet” as prerequisites for legitimate national unity is also historically problematic. The Islamic Republic’s founder, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, while a devout Shiite cleric, named the state the “Islamic Republic”—not a Shiite one—emphasizing its universality. The constitution extends official recognition to Zoroastrians, despite Zoroastrianism not being among the Abrahamic faiths. Such inclusivity was meant to bind the diverse cultural and religious strands of Iranian identity, not reduce them to ideological conformity.

In his remarks, Mr. Jalili also ventured into the metaphysical realm, claiming that Iran’s “being” is inseparable from its “spiritual essence”—a line of argument critics say is far too abstract to unify a complex society. As one commentator pointed out, “People disagree fundamentally on what constitutes ‘spirituality.’ For some, it is embodied in Rumi; for others, he is a heretic. For every Molavi, there is a Majlisi. But when one says ‘Iran,’ everyone knows what that means.”

What makes Mr. Jalili’s intervention more politically consequential is its potential to shrink, rather than expand, the ideological tent of the Islamic Republic at a moment when cohesion is in short supply. By implying that only those aligned with a particular theocratic reading of patriotism truly belong, he risks deepening the alienation of a public already fatigued by state dogma and economic hardship.

There is also a practical contradiction. If nationalism is such anathema, why is the state broadcaster still branded as Seda-ye Melli—the National Broadcaster—and not the “Voice of the Islamic Ummah”? Why was the post-2021 mayoral slogan for Tehran briefly changed to “Tehran: The Metropolis of the Islamic World” before being quietly abandoned in favour of the more inclusive “A City for All”? If religious framing is to be the primary register of public discourse, critics ask, why does the state so frequently fall back on national branding when it needs public support?

The answer may lie in the very demographic the Islamic Republic increasingly struggles to address. In a fragmented society, riven by generational divides, economic inequality, and political disenchantment, nationalism remains one of the few concepts with universal traction. Unlike religious orthodoxy, it does not require theological consensus to command loyalty. And unlike ideology, it can transcend factional lines in moments of national crisis.

Mr. Jalili’s rhetorical offensive, then, is not merely a philosophical or theological exercise. It reflects a broader struggle within the regime—between an older, ideologically purist guard and a younger, more pragmatically nationalistic polity. The stakes are not trivial. As Israel doubles down on its own religious-nationalist project and as Iran faces growing external pressure, the ability to articulate a unifying, inclusive vision of the homeland may prove crucial not only to domestic stability but to strategic survival.

In the end, the real question posed by Jalili’s remarks is not whether Iran should be defined by religion or by nationalism—but whether it can afford the luxury of choosing between them at all.