SAEDNEWS: Superstitions, long-standing beliefs in supernatural forces and unseen influences, are a common part of cultures worldwide.

According to SAEDNEWS, Superstitions are a fascinating aspect of cultures around the world, offering insights into people's beliefs and behaviors. In Iran, these practices are deeply rooted in history and continue to influence daily life, especially in the context of cultural and religious traditions. From knocking on wood to ward off bad luck to the intricate rituals surrounding Nowruz (the Persian New Year), Iranian superstitions tell a rich story about how people navigate uncertainty and seek protection from unseen forces. In this blog, we will explore the origins of these superstitions, their impact on modern Iranian society, and how they vary across different regions of the country, with a special focus on their significance at the Jabalieh Dome in Kerman.

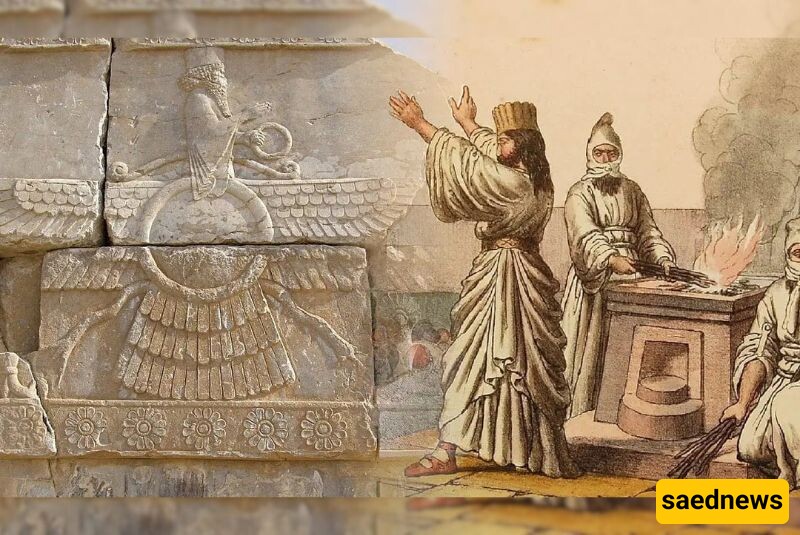

The origins of many Iranian superstitions can be traced back to ancient Persia, long before the advent of Islam. Zoroastrianism, the prominent religion of Persia for over a millennium, played a crucial role in shaping people's worldview. This faith emphasizes the eternal struggle between good and evil, leading to beliefs in supernatural entities capable of influencing human fate. Fire, a vital symbol of purity and protection, features prominently in rituals aimed at repelling evil spirits. Even today, aspects of these ancient beliefs resonate in Iranian superstitions, reflecting a longstanding fear of invisible dangers.

In addition to Zoroastrianism, Persian mythology has contributed a treasure trove of superstitions. Ancient tales of 'Divs' (demons) that bring misfortune and the widespread use of talismans offer a glimpse into how the people of that era understood their world. Over the centuries, these beliefs have been woven into the cultural fabric of Iran, influencing behaviors and practices among the people.

With the arrival of Islam in the 7th century, Persian beliefs blended into this new religious framework, particularly within the Shia branch, which became the dominant sect in Iran. Islamic teachings introduced new practices while reinforcing some pre-Islamic customs. For instance, the belief in the evil eye, which exists across numerous Islamic cultures, intertwined with Persian traditions. Protective charms and phrases like “Mashallah” (God has willed it) are frequently employed to guard against misfortune caused by envy.

In Iran, there’s a unique relationship between revered religious figures and superstitions. Shia saints and imams are often called upon for protection, with many people believing in their ability to influence daily matters. This fusion of religious devotion and superstitious practices highlights how Islamic influence adapted to pre-existing beliefs, creating a rich tapestry of cultural traditions.

Here are some popular superstitions that many Iranians believe in, offering a glimpse into their rich cultural heritage:

1. Knocking on Wood: This practice is commonly used to avoid bad luck or prevent a situation from worsening. When someone shares good news or a sense of relief, they might knock on wood immediately afterward to avoid jinxing themselves. The origins of this superstition are unclear, but it is thought to connect to ancient beliefs that spirits reside in trees, and knocking calls for their protection.

2. Sneezing: When someone sneezes, activities often pause as people say "sabr âmad" (patience has come) and take a moment before continuing. Even those who may not consider themselves particularly superstitious often participate in this brief ritual, especially during allergy season when sneezing is more frequent.

3. Floating Tea Leaves: Tea is an important part of Iranian culture with its own superstitions. If tea leaves float to the surface while a glass is being poured, it is believed that guests will arrive soon. The number of floating leaves is thought to correspond to the number of guests expected, and the shapes of the leaves are even believed to reveal details, like the height of visitors.

4. Things Happening in Threes: A prevalent belief is that misfortune tends to occur in groups of three. For example, if a child suffers a minor injury, and soon after, news of a relative’s small accident arises, many expect a third unfortunate event. People often say, "khodâ be kheyr kone sevomisho" (God protect us from the third one) as they brace for what may follow.

5. Chaharshanbe Suri: Celebrated on the last Wednesday before the Persian New Year (Nowruz), this festival incorporates ancient rituals, including jumping over bonfires while chanting, "Sorkhi-ye to az man, zardi-ye man az to" (your redness be mine, my paleness be yours). This act symbolizes purification, transferring negativity and illness to the fire in exchange for health and vitality. The practice reflects a blend of pre-Islamic Zoroastrian beliefs with Islamic influences, reinforcing the importance of fire in Iranian culture.

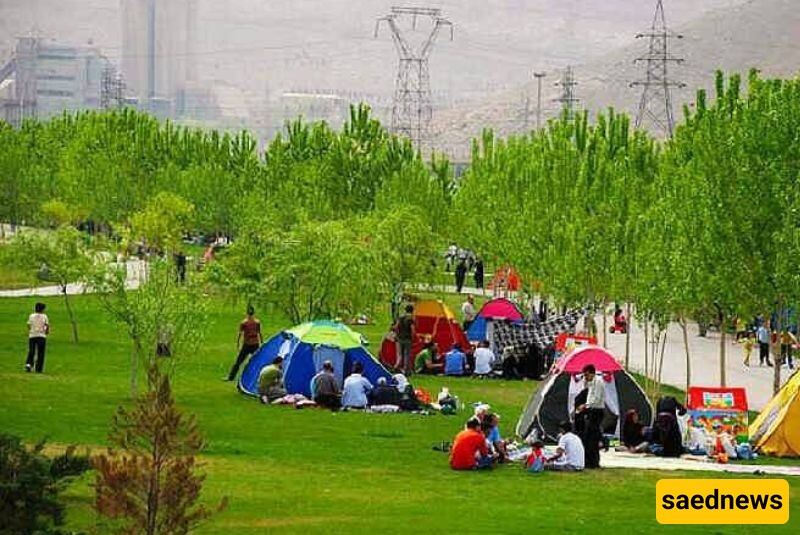

6. Sizdeh Bedar: The 13th day of Nowruz is dedicated to preventing bad luck. On Sizdeh Bedar, Iranians spend the day in parks and natural spaces, believing that outdoor activities ensure good fortune for the year ahead. Staying indoors, in contrast, is seen as tempting fate.

7. Tying a Knot in Nowruz Sprouts: As part of Nowruz celebrations, unmarried girls tie knots in sprouts grown from wheat or lentils, wishing for marriage in the coming year before disposing of these sprouts on Sizdeh Bedar.

8. Itchy Palm: Similar to other cultures, an itchy palm is often interpreted as a sign that money is on the way. An itching left palm suggests a financial loss, while an itchy right palm indicates that wealth is not far off.

9. Spilling Water for a Safe Journey: Spilling water is seen as a sign of good fortune. When someone departs on a trip, family members throw water behind them to ensure a safe and successful journey, with hopes for their quick return.

10. Animal Superstitions: Some animals carry significant superstitions; for example, a hooting owl is seen as a bad omen signaling death or sadness, while a group of crows may indicate good news or a wedding. A rabbit crossing one’s path is thought to bring good luck.

11. Astronomical Beliefs: Although many of these beliefs have faded, there was once a strong belief that eclipses indicated God’s anger. Villagers would bang pots to ward off the perceived negativity. Comets were often associated with the deaths of influential figures.

12. Evil Eye (Cheshm Zakhm): The belief in the evil eye is widespread in Iran. It is said that a jealous or envious gaze can bring harm to people or their possessions. To combat this, many Iranians wear protective talismans, with the blue eye symbol being particularly popular. Common phrases like “Mashallah” also help deflect potential harm.

13. Burning Esfand: Burning esfand (wild rue seeds) protects against the evil eye. The seeds are lit in a container, and the smoke is waved over the heads of loved ones while saying protective phrases. This ritual not only serves as a way to ward off negative energies but also provides a sense of comfort and security.

Even in contemporary Iran, superstitions remain influential, especially when it comes to major life decisions such as business ventures. Many people consider auspicious dates for new contracts, property purchases, or launching new enterprises. Notably, certain numbers are avoided due to their negative associations. This interplay between pragmatism and superstition highlights the persistent role of these beliefs in everyday life across various contexts.

As Iran progresses through urbanization and modernization, the role of superstitions has evolved, particularly in larger cities. Increased access to education, scientific insights, and modern technologies has led many younger Iranians to question or even reject traditional superstitions. In metropolitan areas, practices like consulting fortune tellers or using amulets for protection are becoming less common, as many perceive these beliefs as outdated.

However, a noticeable generational divide persists. Older Iranians, especially those rooted in rural or traditional backgrounds, are more likely to hold onto superstitions and rituals. Conversely, younger Iranians, particularly those in urban environments, tend to perceive these customs as curiosities rather than guiding principles. This generational gap reflects broader societal changes, as Iran continues to navigate the complex balance between tradition and modernity.

For tourists visiting Iran, understanding the superstitions that still play a role in daily life can offer valuable insights into the country's culture. While not all Iranians actively practice these beliefs, many incorporate them into their family traditions and rituals, providing a rich cultural experience for visitors. Appreciating these customs with respect will enhance the connection tourists have with the local culture and provide a deeper understanding of the Iranian way of life.

In conclusion, while some may see superstitions as relics of the past, they remain a vital part of many Iranians' lives today. The blend of ancient beliefs, religious influences, and modern adaptations showcases a dynamic culture that continues to evolve while still cherishing the traditions that define it. Whether through rituals at the Jabalieh Dome in Kerman or everyday practices across Iran, these superstitions offer a glimpse into the collective psyche of a nation navigating the complexities of existence.