SAEDNEWS: Takht-e Jamshid (Persepolis), the monumental Achaemenid ceremonial complex near Marvdasht in Fars Province, Iran, is celebrated worldwide as a UNESCO World Heritage site for its monumental reliefs, colossal columns and enduring testimony to 2,500 years of Persian imperial splendour

Takht-e Jamshid — also known as Persepolis or the Arg of Parseh — is among Iran’s most significant tourist destinations and is officially listed on Iran’s National Heritage List as well as the UNESCO World Heritage List.

Visiting time for this attraction: 2–3 hours

Location: Iran, Fars Province, Marvdasht — ancient historical complex of Takht-e Jamshid (Persepolis)

Takht-e Jamshid is a symbol of glory and grandeur in ancient Iran and one of Shiraz’s top attractions. The Persepolis site and its remaining structures are among the most significant historical records of ancient civilization worldwide. As a result, scholars and archaeologists from around the world visit Iran to study and view Persepolis.

Takht-e Jamshid is the legacy of the Achaemenid kings from around 2,500 years ago. Considering the vast extent of the Achaemenid Empire in ancient times — covering large parts of the then-known East — the site reflects the scale and authority of the royal court that ruled it.

What attracts global attention to Takht-e Jamshid is not just its age. Detailed analysis of inscriptions and artifacts from the site has uncovered the sophistication of ancient Persian civilization. The social laws of the Achaemenid period — revealed in documents and inscriptions — continue to surprise historians.

If you're curious about ancient Aryan civilization or want to learn more about Persepolis, read this article. We provide a detailed description and comprehensive information about the site.

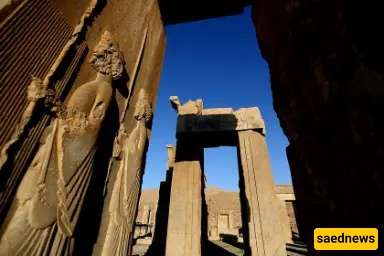

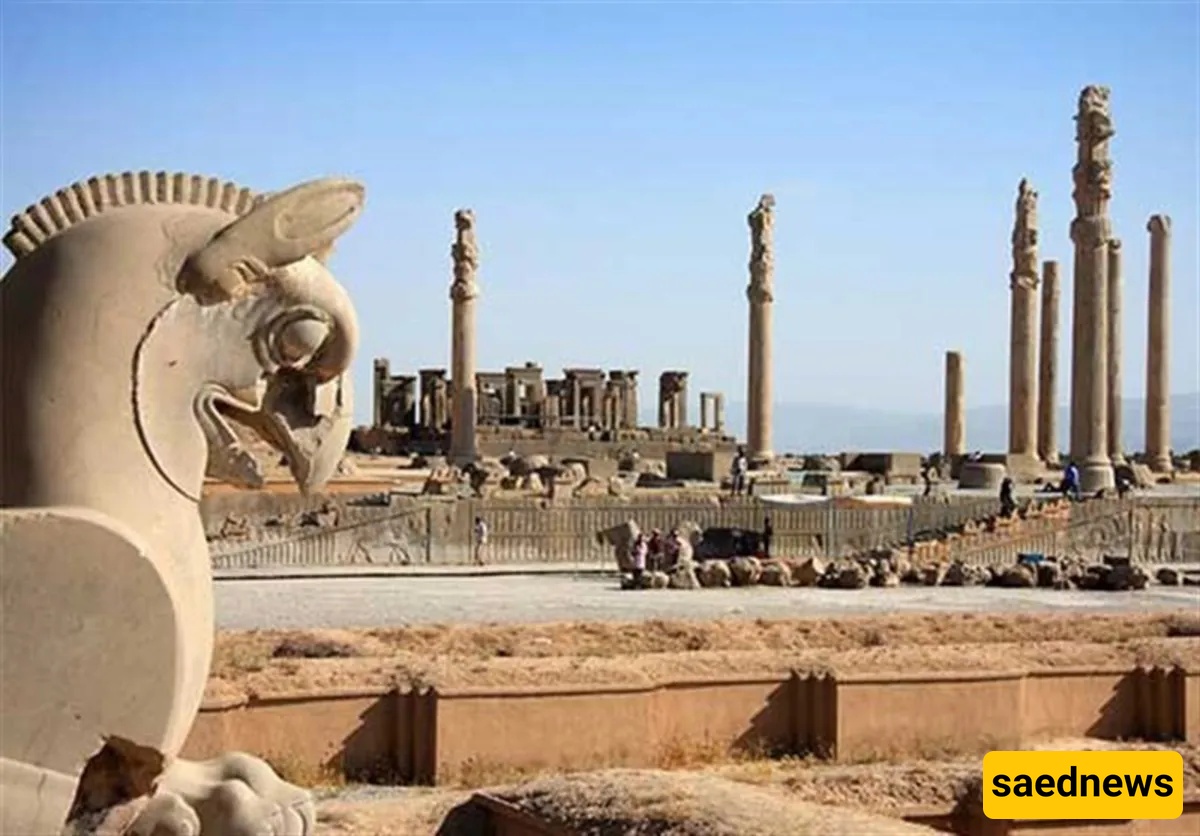

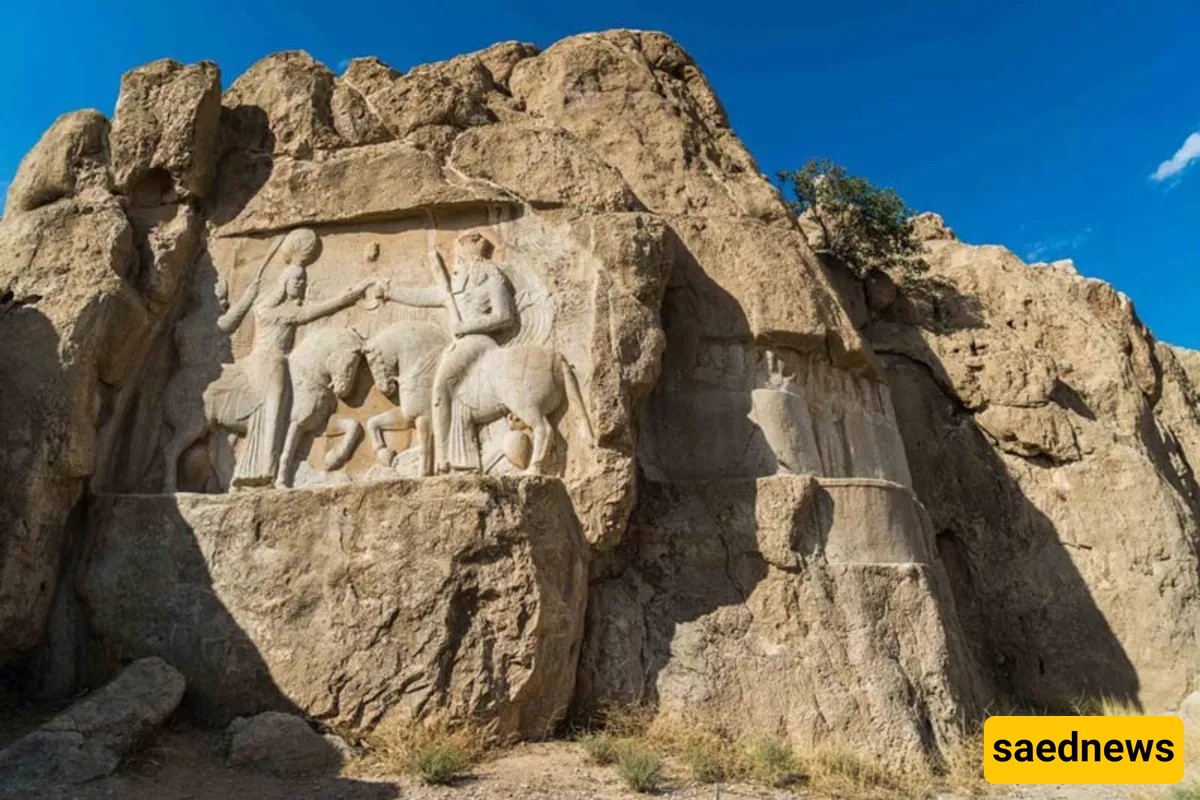

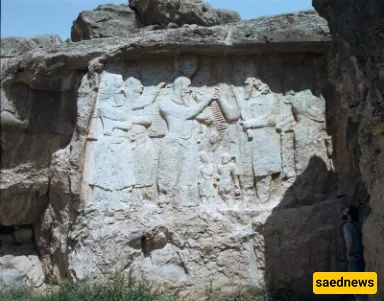

A bas-relief at Persepolis next to a view of the complex.

Persepolis is recognized worldwide as the symbol of Persian civilization. The Persepolis complex is located near Marvdasht in Fars Province, and with convenient hotel options in Shiraz, you can visit easily. The site showcases the architectural grandeur of royal palaces from ancient Persia. At the height of Achaemenid power, kings built large stone palaces on the slopes near Shiraz so later generations would remember the extent of their rule.

The name “Persepolis” is Greek; in Persian, the site is commonly called Takht-e Jamshid or Parseh. Columns, capitals, inscriptions, bas-reliefs, palaces, and gateways that remain at the site are among the most famous monuments of world civilization. The Persepolis plateau — also known as the land of Parseh — attracts visitors from around the world year-round.

Construction of Persepolis—one of Iran’s oldest monumental cities—began about 2,500 years ago at the foot of the Rahmat (Mithra) mountains under Darius the Great. Many architects and artists contributed to the project, and the massive structures were built by large teams of laborers. The inscriptions reveal that the Achaemenid rulers provided wages and benefits to these workers—a notable social policy for the ancient world. According to surviving records, building the complex took approximately 120 years. The advanced culture of the Achaemenid rulers, as reflected at Persepolis, made ancient Persia renowned worldwide.

Construction at Persepolis started around 518 BCE, more than 2,500 years ago. Darius I, the third Achaemenid king, ordered a massive palace complex to be built in the hills near Marvdasht. Building went on for many years, with successive kings adding to the work.

Each palace on the plateau was built during the reign of a specific Achaemenid ruler. The grandeur and elegance of Persepolis still amaze modern architects and engineers; constructing such a complex would be difficult even today. From inscriptions found on the site, Darius’ stated goal was to create a lasting symbol of a progressive Persian state.

To build the palaces and terraces, workers labored for years to carve and level the bedrock. Stone was the main building material — quarried in different qualities — and the cutting, polishing, and transporting of massive stone blocks to great heights is among the most impressive aspects of the project that continues to puzzle today’s engineers and archaeologists.

Construction and completion persisted through the reigns of several Achaemenid kings, with significant projects undertaken under Darius I, Xerxes, and Artaxerxes I. The palaces served as royal residences for a long time and stand as some of the most durable and impressive records of ancient Iran.

Darius’ choice of the hills near Marvdasht was smart: the site has good sun exposure for ceremonies, fertile plains below, and is located on a royal highway — factors with strategic and symbolic importance.

In recent decades, because of damage sustained by the structures, the site has been the subject of multiple restoration campaigns. In 1930 (solar calendar 1309) an American archaeological team conducted excavations and discovered the inscription of Xerxes, enabling the identification of the Queen’s palace. A German team later restored parts of the Apadana palace and its inscriptions in 1935 (solar 1314). Excavations continued through 1940 (solar 1319), uncovering many objects and inscriptions, many of which today are in the Persepolis Museum and the National Museum of Iran; unfortunately, numerous finds were removed from the country in earlier decades and now reside in museums and libraries across Europe and North America. Preservation measures and restoration continue to the present day.

Persepolis thrived until Alexander the Great arrived. In 334 BCE, Alexander invaded Persia with his armies; when he reached the Achaemenid royal center, the city was looted, and much of Persepolis was set on fire. Ancient sources suggest Alexander’s hatred for the Achaemenid kings led to the burning of Xerxes’ palace, and the fire spread, destroying large parts of the complex.

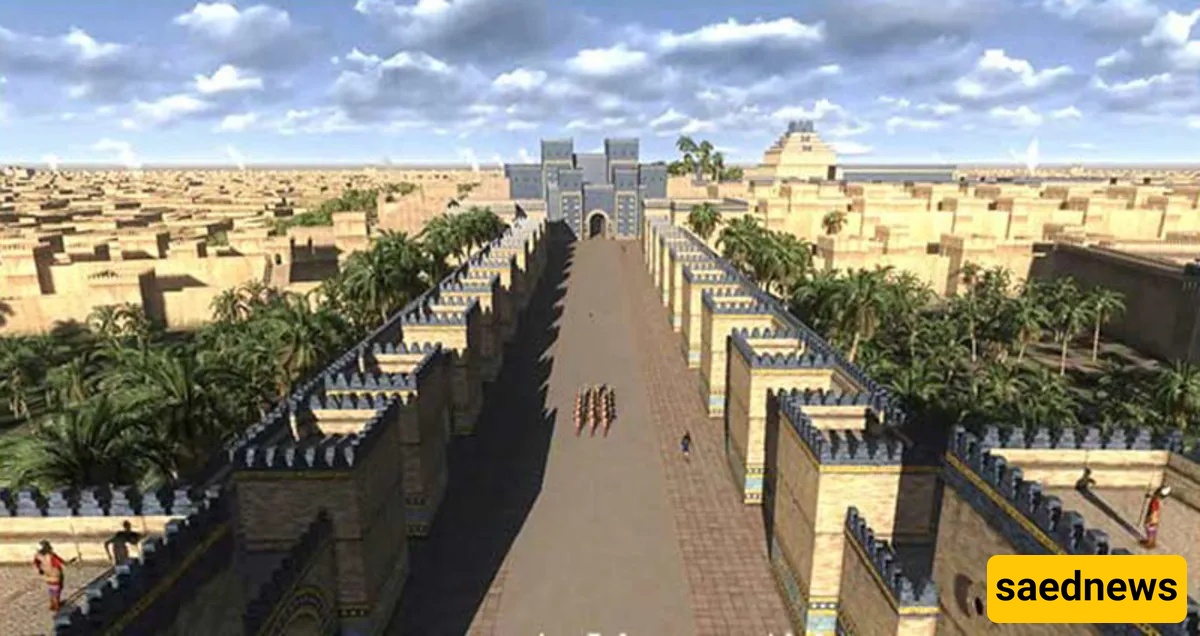

Before its destruction, the palaces of Persepolis sat in a stunning location at the base of Mount Rahmat (also linked with Mithra) and offered sweeping views of the valleys and plains. The interior layout was like a large town with streets running between the palaces. The civil engineering and urban planning were remarkably advanced for their time: enclosed residential areas, organized palace neighborhoods, and ceremonial spaces showed a level of urban design similar to modern principles. The different palaces served specific ceremonial and administrative purposes.

Persepolis’ water and sewage system is a significant architectural feature: channels and conduits were carved between streets to direct rainwater and runoff into designated channels. In short, the palace architecture, interior ornamentation, landscaping, urban planning, and separation of royal from civic areas together serve as a proud testament to ancient Iran, even after 2,500 years.

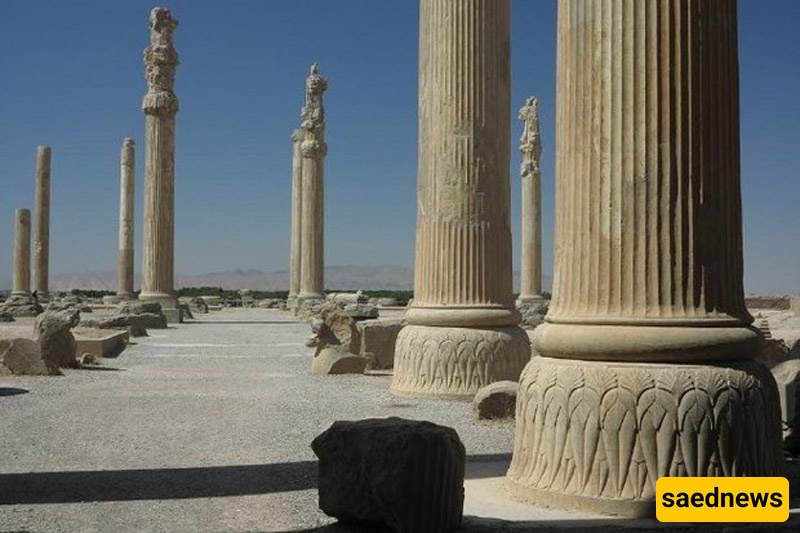

Stone columns at Persepolis

Persepolis’ buildings are over 2,500 years old. Archaeological remains across Iran date back to earlier Elamite and pre-Achaemenid civilizations, but in dignity and scale, Persepolis ranks among Iran’s greatest ancient marvels and is one of the world’s most important archaeological sites.

Persepolis's reputation is international: many museums worldwide display artifacts from the site. Even though the complex is located in present-day Iran, its historical importance makes it a global heritage valued by humanity. Persepolis was added as Iran’s second cultural heritage site on UNESCO’s World Heritage List in 1979.

Persepolis is situated in a pleasant microclimate near Marvdasht and Shiraz in Fars Province. Although much of Fars has a generally warm climate, the Marvdasht area is cooler because of the surrounding hills. The site is located between the villages of Firouzi, Konareh, and Istakhr.

The archaeological site is northeast of Shiraz; the distance from Shiraz to Persepolis is about 70 miles, and Marvdasht is roughly 11 miles southwest of Persepolis. Travel routes depend on your starting point: if you're entering Fars from the north, you can bypass Shiraz by taking the Abadeh–Safashahr highway and following signs to Marvdasht and the Persepolis exit. From Shiraz, take the northern exit toward Marvdasht, drive past the town, and use the Marvdasht–Saadatshahr freeway to reach the Persepolis exit. After passing surrounding villages, you'll arrive at the site entrance. From the underpass, roughly five miles remain to the archaeological complex.

Aerial view of Persepolis complex

The Persepolis site is busiest during Nowruz (Iranian New Year) and other public holidays. Visiting at these times may be less pleasant due to long queues and traffic at the entrance. If possible, choose quieter weekdays and non-holiday periods for a better experience.

Persepolis hosts a sound-and-light show at sunset on selected busy days and special occasions; check with the site administration ahead of your visit for dates and times.

The complex is open for visitation year-round, except on certain religious mourning days, 13 Farvardin (the national holiday of Sizdah Bedar) and other special closure dates announced on the official site. Museum admission and the sound-and-light event require separate tickets.

Opening hours: 08:00–17:00

Sound & light show: 20:30 (arrive at the ticket office one hour earlier to buy tickets)

Entrance fee (per person): 3,000 IRR for domestic visitors; 20,000 IRR for foreign visitors

Sound & light show ticket: 3,000 IRR domestic / 20,000 IRR foreign

Persepolis Museum ticket: 3,000 IRR domestic / 20,000 IRR foreign

Note: Because of the COVID-19 pandemic, the site had intermittent closures starting 1 Esfand 1398; public health conditions have periodically affected opening schedules.

Persepolis under a clear blue sky

Visiting Persepolis during the hottest months can be uncomfortable because much of the site is exposed to direct sunlight. The cooler months — the second half of the Iranian year through late Farvardin (spring) — are the most comfortable. For the site visit, choose early morning hours or late afternoon when temperatures are milder.

In cold seasons, the plateau and surrounding areas become very chilly after sunset, so bring suitable warm clothing. Overcast days are especially good for touring Persepolis because the absence of harsh direct sunlight makes viewing the bas-reliefs more pleasant. A hat and sunglasses are recommended for daytime visits.

Bas-relief at Persepolis

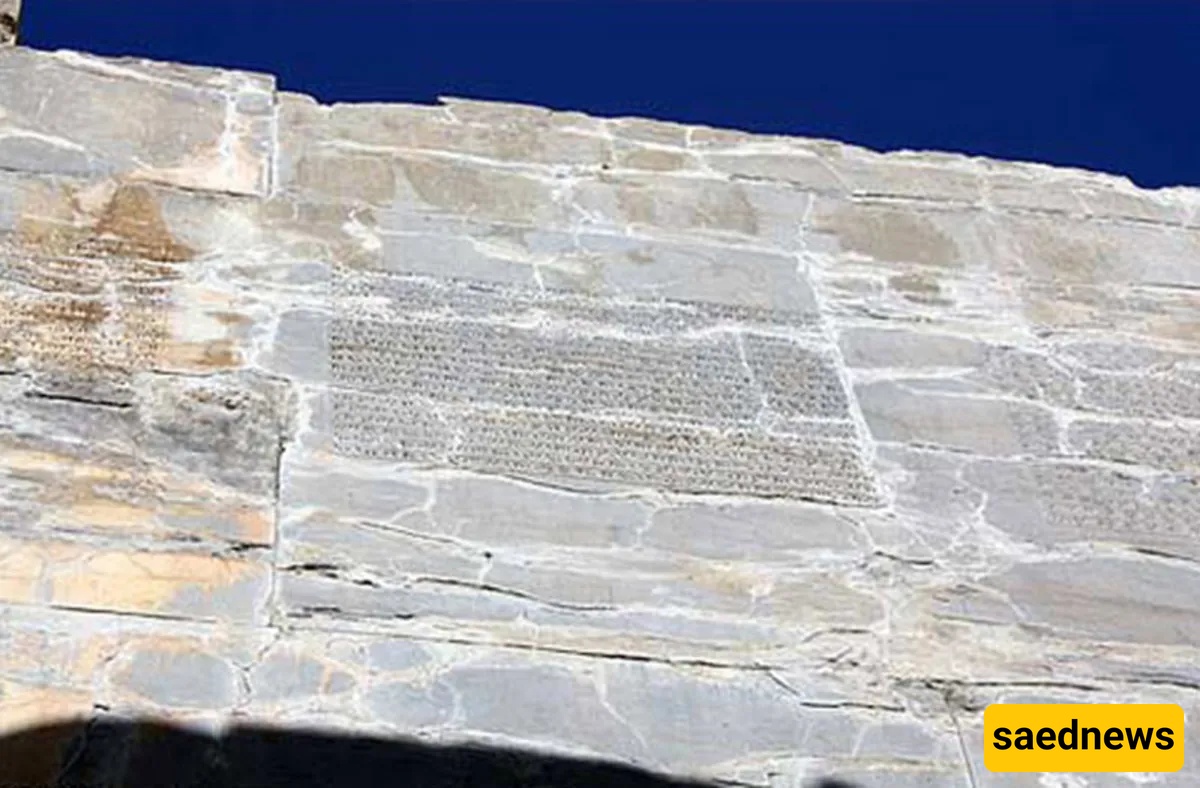

Among the most significant discoveries at Persepolis are the stone inscriptions and bas-reliefs carved throughout the palaces and structures. Due to Persepolis’s age, these artifacts serve as primary sources for understanding early civilizations; scholars continue to work on decoding the inscriptions. Many of the inscriptions have already been translated, but research and decipherment are ongoing worldwide.

A comprehensive study of the bas-reliefs reveals that the Achaemenid rulers sought to communicate unity, social equality, and a rich culture to future generations.

The surviving works date back to the reigns of Darius I (c. 522–486 BCE), Xerxes (c. 486–465 BCE), and Artaxerxes I (c. 465–425 BCE). Although the royal tombs are located at Naqsh-e Rustam near Persepolis, the palaces themselves served as the kings’ ceremonial residences, where they spent extended periods.

Careful analysis of statues, capitals, inscriptions, and other excavated materials has allowed scholars to reconstruct the tools and techniques used by ancient stonecutters. Evidence indicates that melted lead and leather were employed in preserving some objects, and primitive yet effective engineering tools reveal the advanced stoneworking skills of the period. Traces of paint remain on many sculptures; the use of colored stones, pigments, and precious inlays originally made the carvings stunning in their time. Although much of the polychromy has faded, the remaining details demonstrate months or years of meticulous carving.

Bas-reliefs adorn nearly every major palace: the southern, southwestern, and eastern palaces are richly decorated with carvings. These carvings appear on doorways, stairways, lintels, and window frames. Many show kings seated or standing on thrones, surrounded by guards, courtiers, horses, and chariots; long processions of soldiers are also visible on stairways. The Apadana stairways alone feature more than 800 reliefs. The walls of the north stairway echo the south in theme, although some have suffered more extensive damage.

Reliefs of soldiers and attendants are visible on the stairways of palaces built by Xerxes, Darius, and Artaxerxes. The western sides of Darius’ and Artaxerxes’ palaces feature scenes of subject nations. Other panels depict mythic scenes, such as kings fighting legendary demons.

Overall, Persepolis features over 3,000 bas-reliefs with repeating motifs. The quantity and quality of these carvings surpass other contemporary Achaemenid reliefs found in Fars, suggesting that high-quality stone carving thrived at Persepolis. The initial excavations were conducted by an American archaeological team led by Professor Ernst Herzfeld in the 1930s and continue to this day. Many of the inscriptions documented by those teams have been published.

Inscription of Darius the Great (Darius I) — paraphrased translation:

I am Darius the king, king of kings, ruler of many nations, son of Vishtaspa the Achaemenid, the one who built this palace. By the will of Ahura Mazda, the great, who granted me this prosperous realm of Persia, the fine horses, and the good men, I fear no one else. May Ahura Mazda protect this realm from enemies, drought, and falsehood. I, Darius the Great, king of kings, ruler of many nations — these are the lands I added beyond the Persian people, lands that came and paid homage to me: Elam, Media, Babylon, Arabia, Assyria, Egypt, Armenia, Cappadocia, Sardis, the Ionian lands — by the sea and beyond — Scythia, Parthia, Zarang, Herat, Bactria, Sogdiana, Khwarezm, ... and others. May Ahura Mazda preserve me and this royal house.

Inscriptions of Xerxes (Xšayāršāh) — paraphrased translation:

“Great is the god Ahura Mazda, who created this earth, sky, and man; who created joy for humans; who made Xerxes king, one ruler among many. I am Xerxes, the great king, king of kings, ruler over lands with many different peoples; king of this vast and distant earth, son of Darius. By the grace of Ahura Mazda, I built this hall that unites all lands. Many noble structures in this Pars (Persepolis) were built by my father and me; everything that appears beautiful, we built by the will of Ahura Mazda. May Ahura Mazda preserve me, my kingdom, and all that I and my father have built.”

Inscription of Artaxerxes I (or inscription attributed to Artaxerxes / Ardaxšīr) — paraphrased translation:

Great is the god Ahura Mazda, who made the sky, the earth, and mankind; who created joy for the people; and who made Artaxerxes king. By the will and support of Ahura Mazda, I completed the palace my father Xerxes had begun. May Ahura Mazda make my reign and what I have built everlasting.

These paraphrases highlight the main themes: royal legitimacy, pious invocation of Ahura Mazda, and lists of subject lands. The original inscriptions are in Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian versions across the monument.

Based on a detailed study of the reliefs and inscriptions, scholars conclude that the Achaemenid rulers aimed to convey a message of unity, social equality, and a rich culture — which helps explain Persepolis’s global fame.

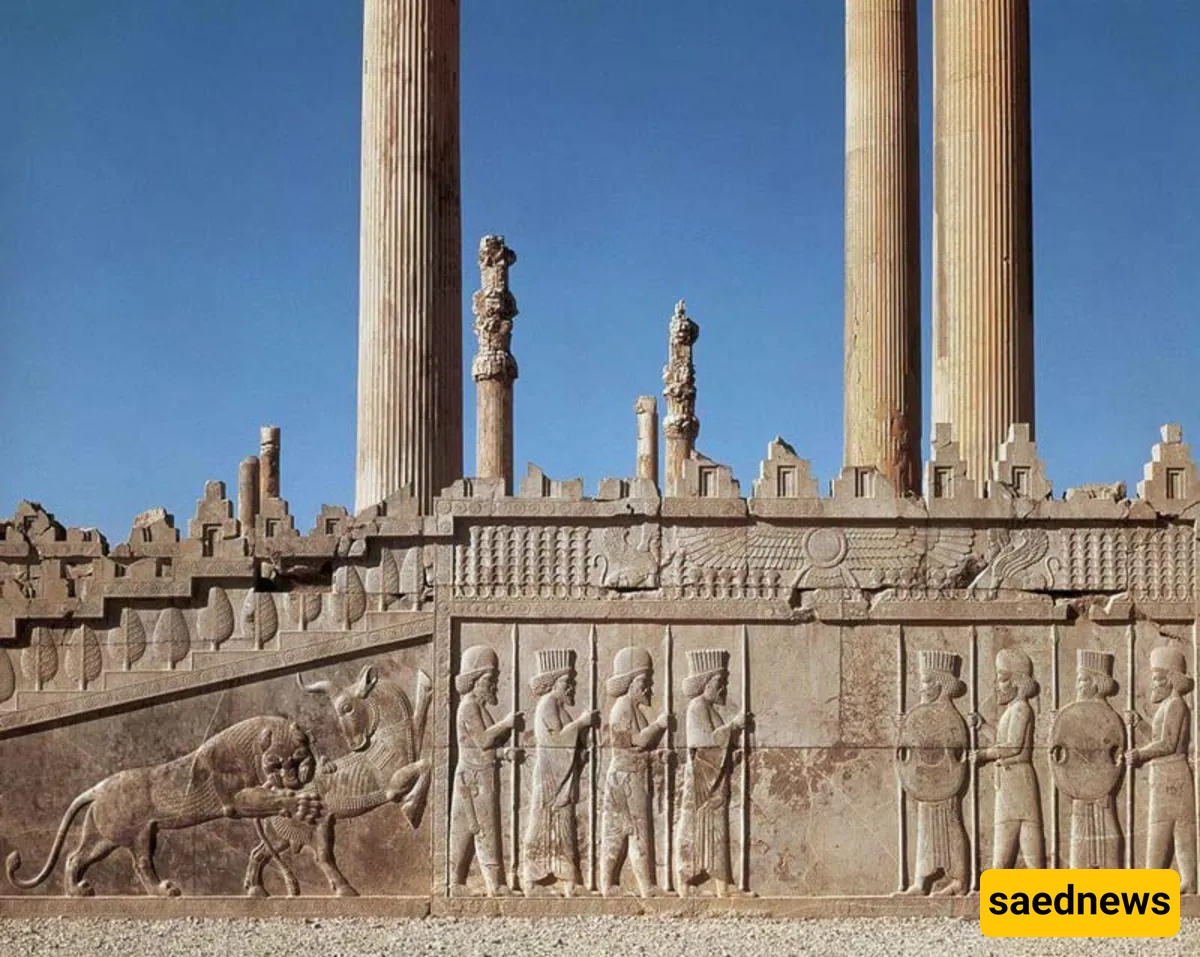

Columns and bas-reliefs at Persepolis

Among Persepolis’s most famous surviving structures are its columns and capitals. These columns are tall and heavy; their construction continues to fascinate architects and archaeologists.

The columns are remnants of the once-great palaces’ massive superstructures; studying them reveals the size of the original halls. Of the 72 columns in the Apadana, only 14 are still standing today.

Each original column rose to over 20 meters and weighed approximately 85 tons. The Apadana’s main hall depended on three porticoes supported by 12 rows of columns; the eastern portico is topped with double-headed lion motifs, while the western portico features ox figures. The capitals of the main hall also took the shape of bulls; remnants of paint on the capitals suggest they were once vividly decorated. The grooves, reliefs, and motifs across these features are exceptionally consistent, with only minor differences in detail. Although much of the original splendor is gone, the sculptural finesse remains clear.

Columns and capitals from Persepolis have become iconic symbols of Iran’s ancient history and are commonly featured in modern depictions of Persian heritage.

The Persepolis complex is composed of distinct sections. Generally, palaces and buildings occupy the central flat terrace and extend to the south, southwest and east. The site’s entrance is a grand staircase leading up to the terrace. Below we describe the primary sections of the complex.

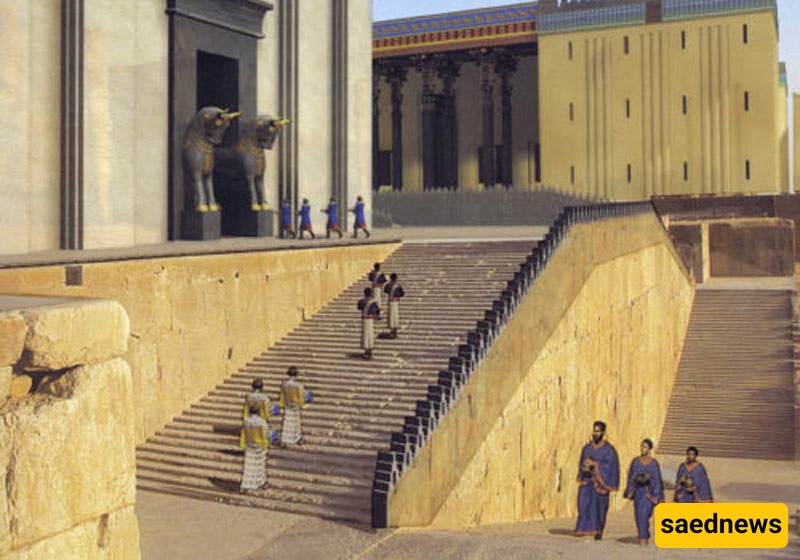

Entrance stairway of Persepolis, viewed from below

The entrance stairway consists of two parallel, symmetrical flights of steps. The space between the flights is paved stone and the steps form a zigzag route ascending roughly 12 metres to the palace platform. The steps are shallow and easy to climb — possibly designed to facilitate mounted access. Entry beyond certain areas was prohibited historically as a sign of respect to the king. Along the stairway are small crenellated refuges about 64 centimetres high with rectangular niches; many of these features are now partially ruined.

The stair treads are fashioned from large stone blocks set without mortar; each block is cut to form four or five steps, many of which show wear from centuries of use. The stairs lead to the Gate of Nations.

Frontal view of the Gate of Nations (Persepolis)

At the top of the entrance stairway, about 22 meters from the end, stands a small palace called the Gate of Nations — named because envoys from subject nations would enter here on their way to the central palaces. Evidence indicates its construction or renovation took place during Xerxes's time; the project may have started under Darius but was finished under Xerxes.

The Gate of Nations features tall mudbrick walls, four soaring columns, and three doorways. The main hall covers over 600 square meters. Its roof rises about 18 meters high, and the columns are roughly 16 meters tall. The Gate’s columns are among the best-preserved in Persepolis: the lower part has a bell shape with vertical fluting, topped with a rounded stone cylinder that supports an intricate capital carved with floral designs, crowned with a half-bull capital.

The southern portal of the Gate of Nations is taller than the eastern and western portals but does not have extensive relief sculpture. On each side of the western portal, two large bull figures face west over the plain: these guardian figures (known in many ancient traditions as sphinx-like guardians) feature a mix of animal and, in some places, human characteristics. Above the statues, inscriptions in three scripts — Old Persian, Elamite, and Babylonian — are carved in cuneiform.

The inscription states (paraphrase): “Great is the god Ahura Mazda, who created this earth, who made Xerxes king — I am Xerxes, the great king, king of kings... By the will of Ahura Mazda I built this palace of all the lands…”

Beyond the western portal, a large chamber with four columns once stood, surrounded by a raised bench. The northern bench features a central projection resembling a table. Interior surfaces were once covered with tiles of green, blue, and orange. Examples of such interior ornamentation can be seen at the Persepolis Museum. The southern portal opens to the northern courtyard of the Apadana palace.

The eastern portal mirrors the western in shape but features human-headed winged sphinxes instead of bulls; these figures face the mountainous east and the northern courtyard of the Hundred-Column Palace. The reconstructed eastern portal was reinstalled in its current position after restoration. The street connecting this gate to the Hundred-Column Palace is called Sepahan Street. The Gate of Nations served as a reception or waiting hall.

View from above of the royal treasury

The Treasury of Persepolis lies east of the Persepolis Museum and south of the Hundred-Column Palace. The remains of this massive building are enclosed by high walls and separated from neighbouring palaces by broad streets. Believed to be among the earliest structures at Persepolis, it was built during the reign of Darius and first used for administrative purposes.

On the western side of the Treasury were small guard rooms; to the east a large courtyard opens onto colonnaded porticoes and several halls. The interior is composed of three halls, each with four columns, a two-column room and two large halls linked by a corridor. The building’s columns were originally wooden and richly decorated. Excavations in 1952–1954 uncovered a pair of two-headed eagle capitals north of the Treasury that may have adorned the entrance of one of the palaces; they were not relocated in antiquity.

Archaeologists found evidence of a later extension to the Treasury, likely to increase storage capacity. Among the most important finds from this complex are two dark blue marble reliefs showing the seated king flanked by courtiers and soldiers. These panels were originally placed at an entrance and later removed to the Treasury; today one resides in Persepolis and the other in the National Museum of Iran in Tehran.

More than 600 Elamite tablets were found in the Treasury, recording workers’ wages and payments. These tablets provide precise information on labour organisation, the nationalities of workers and equal pay for women and men—evidence that undermines earlier assumptions that slaves alone built Persepolis. The tablets bear employers’ seals and are invaluable historical records. Archaeologists also deduced that a major fire occurred in the Treasury, destroying many documents.

Remaining columns from the Hundred-Column Palace

The “Hundred-Column Palace” (also called the Throne Hall) was the second-largest palace in Persepolis. Named for its central hall of 100 columns, the appellation contrasts with earlier finds of smaller 100-column halls in the Treasury; the title stuck because of this hall’s grandeur.

Known in later periods as “Sad Sotun” (Hundred Columns), the palace stands east of the Apadana courtyard. Construction began under Xerxes and was completed under Artaxerxes I. A foundation inscription reads:

“King Ardašīr says: This house was begun by my father Xerxes; by the favour of Ahura Mazda I, Ardašīr, completed and perfected it.”

Scholars date the hall’s construction between c. 470–450 BCE. Ten rows of ten columns — each adorned with sculpted capitals of double-headed bulls — supported the main hall. Column heights reached approximately 14 metres. Only two of the hall’s columns remained until the 1930s when they were transported to Chicago (a practice now controversial).

The palace’s northern gateways were taller and bore bas-reliefs of Artaxerxes seated on the throne; similar carvings were found in the Treasury and the Three-Door Palace. Two gateways together display reliefs of 100 soldiers, symbolically representing the hall’s hundred columns.

Across Persepolis, designers often used numerical symbolism linking motifs, columns and gateways — for example, matching the number of column-carved soldiers to the hall’s columns, equating martial strength with the pillars of rule. The southern gateways of the Hundred-Column Hall display processional scenes of the king being carried on a throne, indicating ceremonial entrances.

The main hall covers more than 4,600 square metres — larger than the Apadana’s main hall but with a floor almost two metres lower. Evidence of burning from Alexander’s assault is visible throughout. The hall is rectangular with eight entrances and numerous side rooms.

Bas-reliefs of the Hadysh Palace

Xerxes’ palace, commonly called Hadysh, is another notable building at Persepolis. Inscriptions claim Xerxes commissioned its construction. Located east of Palace H and south of the main terrace, the Hadysh palace shows signs of initial foundations laid under Darius but completion and decoration under Xerxes.

The Hadysh runs east–west and rises roughly 18 metres above the plain. The palace covers about 1,500 square metres and connects by stairways to Darius’ palace and Palace H. The western stair survives, while eastern stairs have been lost and partially restored.

The main hall was supported by wooden columns, and a 12-column portico stood to the north. The principal western and eastern gateways display depictions of Xerxes; inscriptions in Elamite, Old Persian and Babylonian proclaim Xerxes as builder, though some northern inscriptions mention Darius — a source of scholarly debate about the building’s construction sequence.

Before destruction, the Hadysh bore decorative carving distinct from other Persepolis monuments, though much was lost in the conflagration. Xerxes used the Hadysh as a private residence and the palace commanded a striking view of the Marvdasht plain.

Crenellations of Palace H at Persepolis

The palace known as Palace H or the H-Building belongs to the southwest sector of the terrace, west of the Hadysh palace. The carved stairways flanking it remain in a semi-ruined state. An inscribed fragment indicates that Xerxes began some works and Artaxerxes I completed them. The western and southern edges of the building are decorated with crowning crenellations that show bull-head motifs. Restoration workers Tilia and his wife uncovered fragments of these crenellations and reinstalled them.

The function of the bovine-headed crenellations is debated — whether they were defensive or symbolic remains unclear. The crenellations alternate in size and are decorated with arrowheads and crosses.

The original design included two phalanxes of 16 Persian spearmen arrayed opposite each other alongside an Old Persian inscription; similar inscriptions found on other stairways reveal the origin of the steps and their later reuse. Scholars including the German archaeologist Schmidt have suggested that some of the sculpted stair fragments were relocated from other monuments and reassembled in new contexts during later restorations.

Extensive research by the Tilia team indicates the present stair was originally much more ornate, featuring images of thirty groups presenting gifts; fragments of these scenes lie scattered across the site.

An inscription of Artaxerxes I in Palace H confirms the king’s devotion to Ahura Mazda and continues the tradition of royal piety recorded throughout Persepolis.

Inscribed stairways of the Three-Door Palace

The Three-Door Palace sits at the complex centre and is named for its triple openings providing connection to adjacent palaces. The central hall functioned as a council chamber and reception area for formal and informal audiences with foreign dignitaries and court officials; the stairways are carved with images of court nobles — hence its alternative names “Council Palace” or “Gate of Kings.”

The main building is rectangular with a central square hall supported at its corners by tall columns. The principal eastern doorway opens to the southern corridor of the Hundred-Column Palace; the western entrance leads to the southern courts of the Apadana; the northern doorway faces the Apadana courtyard.

Symmetrical staircases flank the hall and the walls are covered with bas-reliefs of dignitaries, animals and soldiers. The west wall reliefs remain in good condition while east wall carvings are mostly lost. The reliefs exhibit a high level of design sophistication and motion — features that lead scholars to date parts of the palace later than Darius’ reign. Many experts attribute the palace’s inception to late in Xerxes’ period with finishing and carving occurring under Artaxerxes I.

The walls of the central hall were built of raw bricks and once covered with coloured tiles; the columns were topped by bull-shaped capitals and the ceiling adorned with carved and painted woodwork. A circular stone in the floor marks the point where, at sunrise, sunlight would fall vertically — an architectural orientation with ceremonial resonance.

One intriguing aspect of Persepolis’ relief design is the directionality of figures: the movement and positioning of kings and soldiers indicate palace entrances and exits. The stairway reliefs display 28 figures bearing gifts and carrying the king in procession — representations of tributary nations under Achaemenid rule.

Design analysis shows eastern entrances served as principal access routes and northern courts served as reception zones, while exits lay to the west and south. Some complex areas appear to have been constructed later than the Achaemenid era based on stylistic differences.

Remaining columns of Apadana Palace at Persepolis

The Apadana Palace — also called the Audience Hall or Bar Palace — stands among Persepolis’ most magnificent structures. Construction at Apadana began under Darius I and continued under Xerxes; the final work is sometimes attributed to both. The building campaign lasted nearly 30 years and Apadana shares stylistic affinity with Darius’ palace at Susa.

The great hall was square, with 36 columns in the main chamber and three porticoes to the north, east and west; each portico featured 12 columns. Of the Apadana’s original 72 columns only 14 survive, one of which has been partially reconstructed. At each corner of the hall towers and guard rooms were placed.

The Apadana’s central hall stood three metres above the surrounding courtyard and rested on the mountainside. The northern stair adjoins the north portico; the eastern stair adjoins the east portico, providing access between the main hall and adjacent palaces and courtyards. Ramp and stair walls are adorned with elaborate reliefs and inscriptions.

The Apadana’s splendour was unmatched: in its prime the hall could accommodate more than 10,000 people. Capital heads of two-headed bulls crowned the columns and the lower column blocks were assembled from two interlocking stones. The chamber walls included drainage for rainwater to prevent collapse and the interior was finished with green and grey plaster.

The north portals were the main entrances and once bore gold overlay; fragments of gilded fittings with three winged bulls were discovered in 1941. Matching portals existed on the southern side connecting to storage and service courtyards. The hall’s light entered through openings in the east and west walls and five large niches decorated the south wall.

In each corner of the hall, Darius ordered caches to be buried containing two gold and silver tablets inscribed in Old Persian, Elamite and Babylonian cuneiform — one pair of which is now housed in the National Museum of Iran in Tehran. The southern colonnade provided the royal loggia from which the monarch could access all parts of the complex. Among portable objects found here are a golden crown fragment now in Tehran’s museum. Coins and other artefacts of the Achaemenid period were also discovered in the Apadana.

The eastern portico’s carved reliefs are among the site’s most exquisite: six of twelve columns of the eastern portico survive with richly detailed double-headed bull capitals. The reliefs include famous profile images of Persian guards and soldiers and scenes of emissaries bearing gifts — images widely associated with Persepolis worldwide.

Other notable motifs in the Apadana include rosette panels with twelve petals, winged discs, tall palms, winged lions and sphinxes. Each motif carried symbolic meaning: the palm as fertility and prosperity, the sphinx as guardian, the winged lion conveying royal might and the winged ring symbolising sovereign authority.

Although earlier scholars once attributed most Apadana ornament to Darius I, detailed study shows that much of the decoration was completed under Xerxes, with his image appearing in many reliefs and inscriptions supporting his major role.

Exterior view of Tachara (Darius’ palace)

The palace of Darius I, known as the Tachara, is among the earliest constructions at Persepolis. Located southwest of the Apadana and facing south to the sun, the Tachara is sometimes described as the “winter palace.” Owing to the fine polish of its stone work, it is also called the “mirror house” or “hall of mirrors.”

The Tachara sits slightly higher than surrounding courts and its main hall is rectangular, extending north–south. The central hall contained 12 columns, northern rooms each had four columns and the southern portico had eight columns — all originally wooden, now lost. Two-tiered stairways connected northern rooms to the southern portico.

Carved reliefs on stair walls depict three distinct groups identified as servants, chamberlains and Persians — servants are shown carrying whole lambs. Southern walls display scenes with imperial symbols, including the royal emblem and sphinxes. A cuneiform inscription in Old Persian praises Ahura Mazda and proclaims Xerxes’ dominion; the inscription also bears translations in Elamite and Babylonian, attesting to the multilingual royal inscriptions typical of Persepolis.

The Tachara’s primary entrance and halls reflect a luxurious interior once carpeted in red and decorated with precious stone inlay and gold leaf. Many of the palace’s carved fragments are now housed in the National Library of France and other institutions.

Inscriptions throughout the palace praise Darius and record the succession to Xerxes and later kings; numerous later inscriptions from Sasanian and post-Achaemenid eras also appear, including commemorations by Shapur II and others.

Entrance relief of Artaxerxes III tomb

orticoed buildings are constructed without mortar, and the entire structure rests on a platform. A carved tomb face on the eastern side indicates a cross-shaped layout borrowed from the royal tombs at Naqsh-e Rustam, although the lower arm of the cross appears unfinished.

Achaemenid religious beliefs included a reluctance to contaminate the sacred elements—water, earth, and fire—with corpses. As a result, funerary practices favored alternative rites—rock tombs, ossuaries, and stone boxes that held preserved remains. On the eastern slope of Persepolis, a cluster of ossuaries (repositories of bones) has been discovered.

Darius and his descendants chose Naqsh-e Rustam for their royal rock tomb, located a short distance from Persepolis. However, Persepolis itself features a northern chamber carved with similar-style stone tombs. Another southern chamber holds three stone coffins, and a partially finished tomb can be seen south of the terrace.

A carved tomb features reliefs and inscriptions similar to Darius’ tomb; scholars debate the identity of the occupant — possible names include Darius III or Artaxerxes II. The simpler, unadorned northern tomb may belong to Artaxerxes III.

Aerial view of Persepolis

That Persepolis was built more than 2,500 years ago — with such technical precision and artistic refinement — is among its wonders. In other great ancient empires, forced labour and slavery supplied much heavy construction labour. In the Achaemenid core however, records show that men and women received wages and social benefits, including support during pregnancy and childbirth, and equal inheritance rights — a striking social policy for the ancient world.

Architectural ingenuity abounds. Builders used geometric principles akin to a golden ratio in column construction and joined column segments using molten lead — a technique that helped the surviving blocks remain standing through earthquakes. Wooden columns topped by stone capitals are another remarkable feature. The Apadana’s 72 columns once carried massive weight; the capitals carrying two-headed lion statues weigh over one and a half tons each. Parallel stairways across palaces depict kings, nobles and soldiers in procession — an image repeated throughout the complex with relatively little depiction of captivity or slaughter among the carved scenes.

Other notable technical achievements include glazed brick gutters, short pitched ceramic downpipes sealed with bitumen, open channels and stone wells; the water and sewage engineering draws repeated admiration from archaeologists.

The builders assembled the long stone slabs through finely cut joints without mortar — a method that improved seismic resilience. Huge stone slabs up to 250 tons were moved and placed using simple but powerful levers and techniques that permitted the transfer of these astonishing blocks from quarry to site — one of the great ancient engineering feats.

Although many carved and painted surfaces have lost their precious inlays and pigments, surviving tooling marks reveal the extraordinary finesse of ancient stonecutters.

In Persepolis’ inscriptions scholars have also reconstructed aspects of Achaemenid social law: women and men reportedly enjoyed comparable legal rights, women could work and received special support during childbirth, and inheritance laws appear equitable — aspects that astonish modern historians.

Archaeologists are confident that an ancient city once lay adjacent to Persepolis, known in the inscriptions as the city of Parseh, but its precise remains have not yet been fully located; their search continues.

Given the loss of wooden roofs, much of the original superstructure is gone, but archaeological reconstruction — particularly in the former Queen’s Palace turned museum — offers glimpses of how painted, jewelled and richly finished the former interiors must have been.

At the four corners of the Apadana Darius placed gold tablets inscribed with messages of peace and friendship to posterity — a final testament to his intention that these inscriptions endure.

Restored bas-reliefs and an Achaemenid trumpet displayed in the Persepolis Museum

The Persepolis Museum is Iran’s oldest museum building, created by adapting the Queen’s Palace from the Persepolis complex into a museum. The museum’s restoration and conversion began in 1932 under Professor Ernst Herzfeld, director of the Persepolis excavations. Its interior ornamentation uses a symbolic red mortar echoing ancient decorative choices.

The Queen’s Palace (now the museum) originally contained a main hall and numerous rooms; its entrances are decorated with reliefs depicting Xerxes and his attendants, mythical beasts and warrior scenes. Twelve wooden columns once supported the main hall roof, each capped by a double-headed bull capital.

The museum’s main hall has four entrances, each bearing a bas-relief of Achaemenid kings modeled on finds from the site. Objects displayed in the Persepolis Museum include material unearthed in the palaces — fragments of marble statuary, burned tapestry, construction tools, chariot components, bronze bridles, ceramic rhytons and other excavated vessels. Among the most remarkable pieces are two female statues of probable Egyptian provenance discovered at Persepolis.

A reconstructed Achaemenid oboe (surnāy) is on display

At the museum entrance a broad portico is flanked by monolithic stones up to eight metres high and weighing about 70 tons — examples of the large blocks used in the palace constructions. The museum’s storeroom contains over 5,000 objects; about 170 are displayed at any one time and exhibits rotate periodically, encouraging repeat visits.

Alongside Achaemenid material, the museum displays artefacts from earlier and later periods discovered in the surrounding region. The museum is organised into sections:

Pottery and ancient finds from before the Achaemenid era are displayed in this section, including ceramic vessels and stone tools that may date back to the fourth millennium BCE. A winged human figure relief on the southern wall combines Iranian and Egyptian artistic elements, provoking debate over its origin. The eastern wall features a plaster cast of an inscription associated with Kartir, a prominent Sasanian high priest.

A key part of the museum, the Achaemenid Hall exhibits items discovered during the Persepolis excavations. Many Achaemenid finds have been taken abroad in earlier decades and are now housed in European and American museums.

Highlights include carved beads, clay tablets in cuneiform, fragments of animal sculptures (including ox ears and lion heads), daggers, ceramics, vases and weapons. Notable pieces are a burned textile fragment more than 2,500 years old, golden rivets, and the famous inscriptions of Xerxes with Persian and English translations displayed nearby. Stone animal figures, an unfinished dog statue, a prince’s portrait and bronze instruments such as an Achaemenid trumpet are shown outside the display cases.

This section contains Islamic period artifacts, chiefly from the Safavid era and finds from the nearby ancient city of Istakhr. Glazed ceramics decorated with Kufi inscriptions and unglazed pottery with relief patterns form the bulk of the collections, along with glassware, decorated wooden doors and coloured glass fragments.

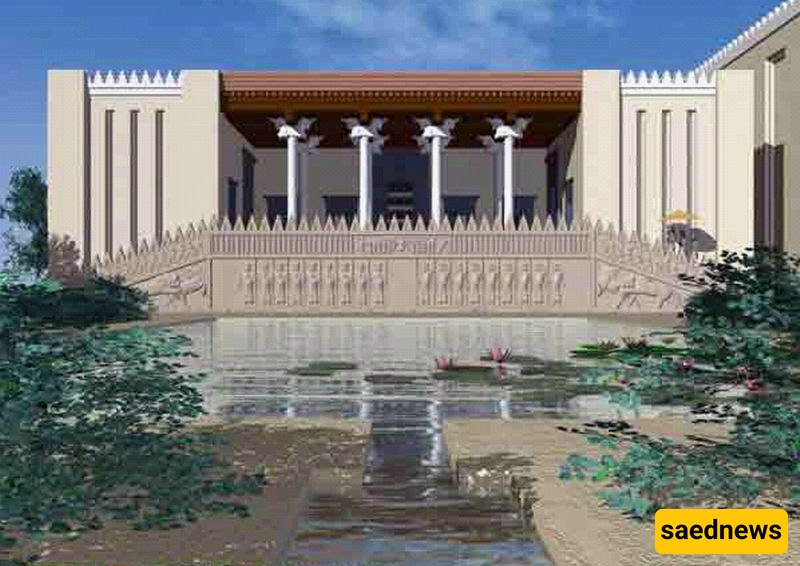

Thanks to extensive archaeological work, designers have produced high-quality reconstructions of Persepolis before its destruction. These reconstructions depict stairways, entrance portals and palace courtyards as they might have appeared in antiquity and give a vivid impression of the former splendour.

If you are visiting Persepolis, several outstanding nearby sites are also worth a visit. These neighbouring monuments represent successive layers of Iran’s ancient cultural history and are among Fars Province’s most important heritage sites.

The royal necropolis at Naqsh-e Rustam lies north of Marvdasht and about six kilometres from Persepolis. The site includes rock-cut royal tombs of the Achaemenid kings and Sasanian reliefs and inscriptions carved into the cliff face. The enigmatic “Cube of Zoroaster” (Ka’ba-ye Zartosht) stands here; its original function remains debated among scholars.

Located about four kilometers north of Persepolis, between Persepolis and Naqsh-e Rustam, Naqsh-e Rajab features Sasanian rock reliefs illustrating royal investiture ceremonies and other regal motifs. It serves as a significant resource for understanding Sasanian history and iconography.

The World Heritage ensemble at Pasargadae stands among Iran’s most significant ancient sites and sits about 73 kilometres northeast of Persepolis. The complex includes the Tomb of Cyrus, the royal garden, the Gatehouse, the tomb of Cambyses and numerous palaces, reservoirs and caravanserais. Pasargadae was the first Iranian site inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List from Iran and traces its roots to the earliest Achaemenid period.

Have you visited the Persepolis complex and the historic city of Marvdasht? If so, please share your experiences and impressions — your observations help fellow travellers and enrich the public record.