SAEDNEWS: Researchers have uncovered compelling evidence of a gathering of ancient humans in Saudi Arabia dating back 7,000 years. The findings are based on a survey of more than 1,000 prehistoric rectangular stone structures.

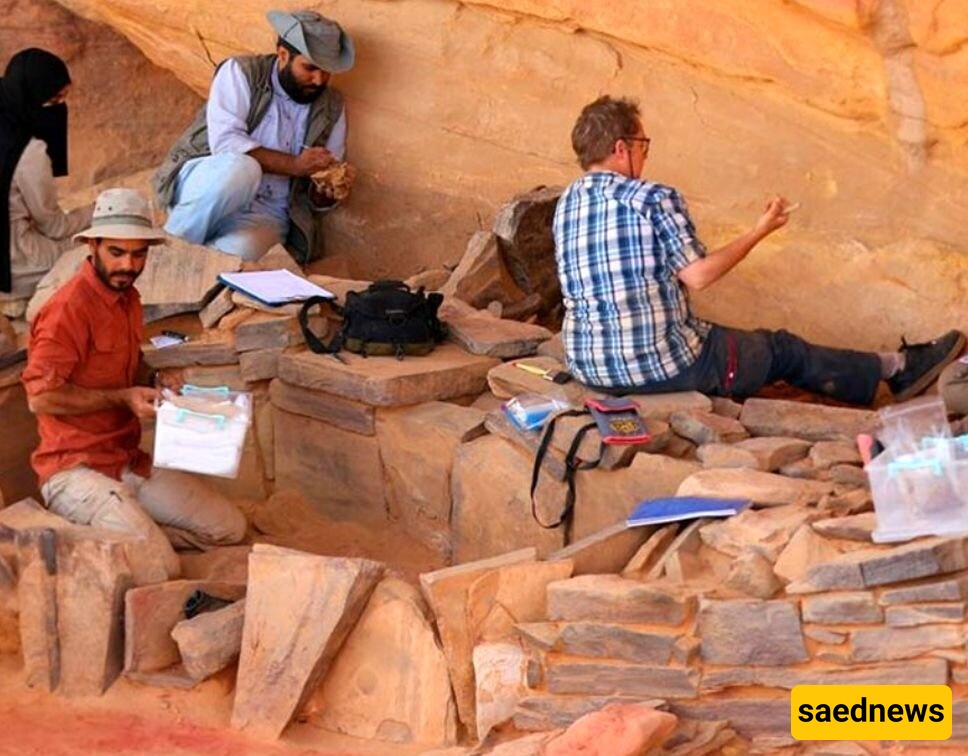

According to Saed News’ Society Desk, recent excavations and subsequent studies of rectangular stone monuments in northwestern Saudi Arabia suggest the presence of a ritualistic sect in the region, dating back to prehistoric times.

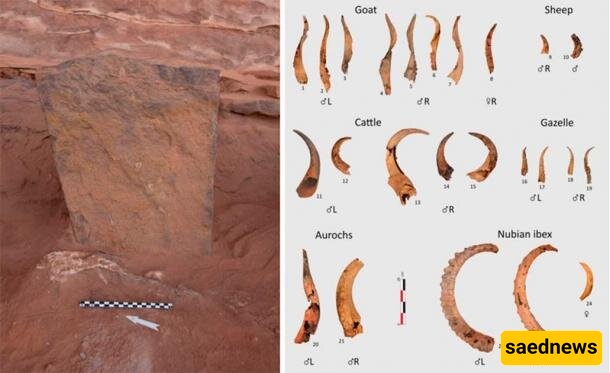

Based on findings—including several fragments of animal bones and the remains of at least nine humans—Neolithic people from the sixth millennium BCE appear to have conducted complex religious, political, and social rituals here.

The notion of a religious sect arises from the deliberate arrangement of skulls and animal horns in specific patterns.

A Ritual Gathering: The First Pilgrimage in History?

Compelling evidence has emerged indicating gatherings of ancient humans in Saudi Arabia around 7,000 years ago. Researchers examined more than 1,000 prehistoric rectangular stone structures—large open-air rectangles with low walls—whose purpose and date remain uncertain. Systematic documentation and study of these structures and other archaeological remains in the region began in 2018.

The recently discovered rectangles measure approximately 40 by 12 meters, with stone walls 2 meters thick. Unfortunately, erosion has reduced their original height.

Researchers emphasize the collective nature of these rituals and suggest that people likely traveled specifically to these prehistoric stone rectangles. These journeys may represent the earliest documented form of pilgrimage.

The abundance of domestic animal species among the sacrificial offerings further sheds light on the spiritual and pastoral lifestyle of these communities. It’s likely that these rectangles served to strengthen social cohesion and define communal territory.

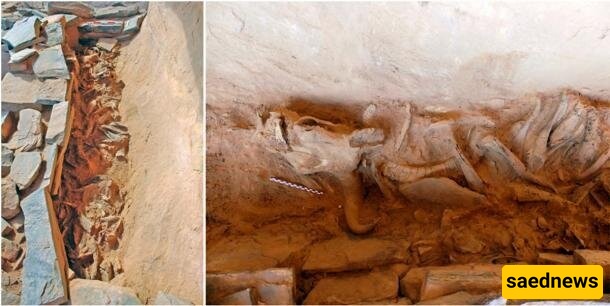

Animal horns and skulls were likely accumulated at these sites during ceremonies. Early reconstructions suggest that nomadic groups gathered and carried these offerings as integral components of ritual practice. Participants entered a compact horn chamber (a smaller rectangle discovered in 2018) one by one through a narrow doorway and passed through a corridor decorated with fire altars before reaching the main enclosure, where they presented symbolic sacrifices on behalf of their social group. Together, these offerings fostered a sense of unity and shared identity among the larger community.

At the heart of the rectangular structure, researchers discovered a probable courtyard containing two fire altars, indicating that rituals likely took place within. Over 3,000 fragments of animal remains, weighing roughly 25 kilograms in total, were found in the structure, dating between 5300 and 5000 BCE.

Among the findings were hundreds of human skulls and animal horns, originally from species such as cattle and goats. Similar arrangements of heads and horns have been discovered at multiple prehistoric sites across the Middle East, including a Yemeni site where cow skulls were displayed in circular formations.

The nine humans discovered include two infants, five adults, one adolescent or young adult, and one child, dating a few centuries after the animal bones. They were likely buried in a collective ceremony. Could these individuals have been the builders of the rectangles? Their exact role remains unclear, as does the primary purpose of the structures themselves.

A 2021 study hypothesized that the rectangles may have been associated with a “cattle cult,” based on the relative scarcity of cattle bones compared with other domestic animals in the region. Another study, published earlier this year, suggested that these structures were constructed during the humid Holocene period (7000–6000 BCE), when the region experienced rising moisture levels alongside gradual drought and desertification. These structures may have served as sacred sites for invoking rain deities and blessing parched lands.