SAEDNEWS: During a period when NASA’s budget was slashed, thousands of tapes were reused to save money. Archivists erased the old recordings to make room for new satellite data. No one realized that among those tapes lay the visual record of humanity’s first steps on the Moon.

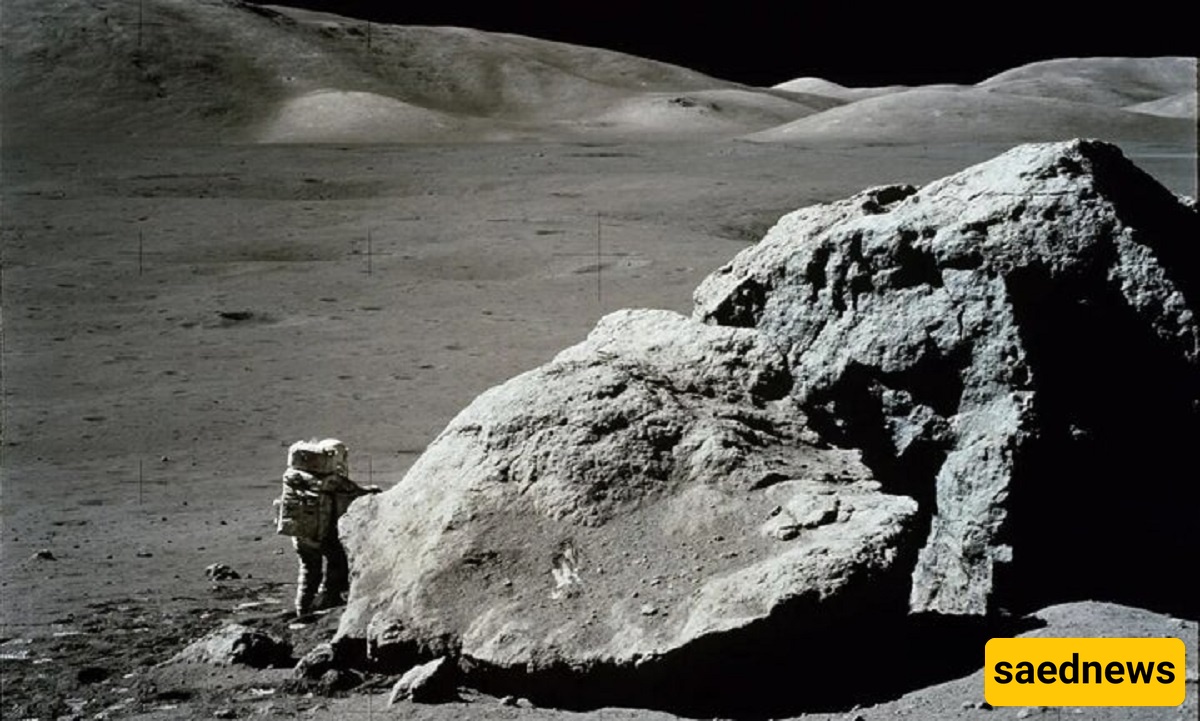

On a summer night in 1969, millions of people on Earth stared silently at black-and-white television screens. A trembling dot revealed the shadow of a human figure descending the ladder of the Eagle spacecraft, setting foot on the Moon. That grainy, noisy image became one of the defining symbols of the 20th century. Yet few knew that a far clearer version, brimming with astonishing detail, existed elsewhere.

According to reports from One Doctor, this higher-quality footage—far superior to the broadcast version—was recorded on special magnetic tapes known as “Slow-scan telemetry tapes.” These tapes captured the Moon’s surface, the subtle shadows, and the slow, deliberate movements of Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin in breathtaking clarity. But decades later, in the 1980s, this human heritage disappeared—without anyone realizing it.

At a time when NASA’s budget was tight, thousands of tapes were reused to save money. Archive staff wiped the old tapes to record new satellite data. No one knew that among those tapes lay the visual record of humanity’s first steps on the Moon. What remains today are only the low-resolution television broadcasts—a dim reflection of one of humanity’s brightest moments.

The original Apollo 11 footage had been captured using Slow-Scan Television (SSTV), a system designed to transmit images across the 380,000-kilometer gap from the Moon. It used smart data compression, storing each frame at high resolution and a frame rate different from the standard TV broadcast of 30 frames per second.

When the signals reached Earth stations like Goldstone in California and Parkes in Australia, they were first recorded on these primary tapes. Only then was a lower-quality version produced for live television. In other words, what the world saw was a second-generation copy of something far more spectacular.

The original tapes contained more accurate colors and depth, showing lunar soil with near-modern clarity. Yet this engineering marvel later fell victim to bureaucratic oversight—a time when no one imagined that erasing a tape could erase part of humanity’s collective memory.

In the early 1980s, NASA faced financial strain and a shortage of equipment. Producing new magnetic tapes for satellite missions was expensive. Archive managers decided to wipe and reuse old tapes.

Around 200,000 tapes were overwritten in the process. With no digital catalog or precise tracking system, no one knew which tapes contained what data. Among them, the original Apollo 11 recordings were simply erased.

By 2006, when researchers sought the original tapes, they found no trace. A clerical decision had destroyed one of the most significant films in human history. Humanity had reached the Moon—but couldn’t preserve the memory of it.

Years later, some cited the lost tapes as “proof” the Moon landing was faked. Independent investigations, however, confirmed the tapes existed and were destroyed purely for economic reasons.

NASA in the 1980s was managing thousands of missions on a shoestring budget. Many administrators did not recognize the historical value of these tapes; fresh satellite data was more urgent than preserving recordings of a completed mission.

Technical studies confirmed there was no contradiction in the mission’s imagery or communications data. The only loss was the original image quality. This wasn’t a conspiracy—it was a painful lapse in scientific heritage management, later becoming a classic cautionary tale for space archives worldwide.

The Apollo 11 tapes show that even the world’s greatest scientific organizations are vulnerable to administrative errors. A small archival decision can leave a cultural imprint for generations.

After the incident came to light, NASA revamped its data management. Today, every space mission follows multi-layered protocols to preserve and digitize records. No raw tape is ever discarded without a backup.

When news of the tape destruction broke in 2006, media around the globe reacted with criticism, satire, and sorrow. People struggled to accept that NASA—the very agency that put humans on the Moon—had erased the recording of that historic moment.

Newspapers ran headlines like “History Erased” or “The World Took a Step on the Moon and Lost Its Memory.” Yet the incident also helped many recognize the true value of archival preservation and scientific history.