You know that moment when a tech billionaire treats sci-fi like a to-do list? Elon Musk is sprinting to stick tiny chips in our brais, promising mind-control perks — and the internet can’t decide if it’s genius, horrifying, or the best prank yet.

Neuralink says a growing handful of people already have its brain implants; early users can move cursors, play games and design 3D objects with thought — and Musk wants to scale fast. Scientists applaud the promise for paralysis and blindness, but safety glitches, animal-welfare rows and skeptical experts mean this race looks more like a sprint with surprising potholes.

There’s a striking image in recent reporting: a participant staring at a black screen, concentrating until a 3D-hand lifts a single finger — controlled by thought alone. It’s the human showpiece of a field that has matured in labs for decades, and Neuralink has become the poster child by promising a future where brain chips do things once confined to science fiction. Rolling Stone’s long profile follows users and lab scenes like this one .

But the measurable news is simpler and harder to ignore: Neuralink announced this month that 12 people worldwide have now received its implants and are using them to control devices — up from seven earlier in 2025. The company says those users collectively have accumulated thousands of days of device use. That’s real progress for a technology that only recently cleared regulators’ early safety hurdles.

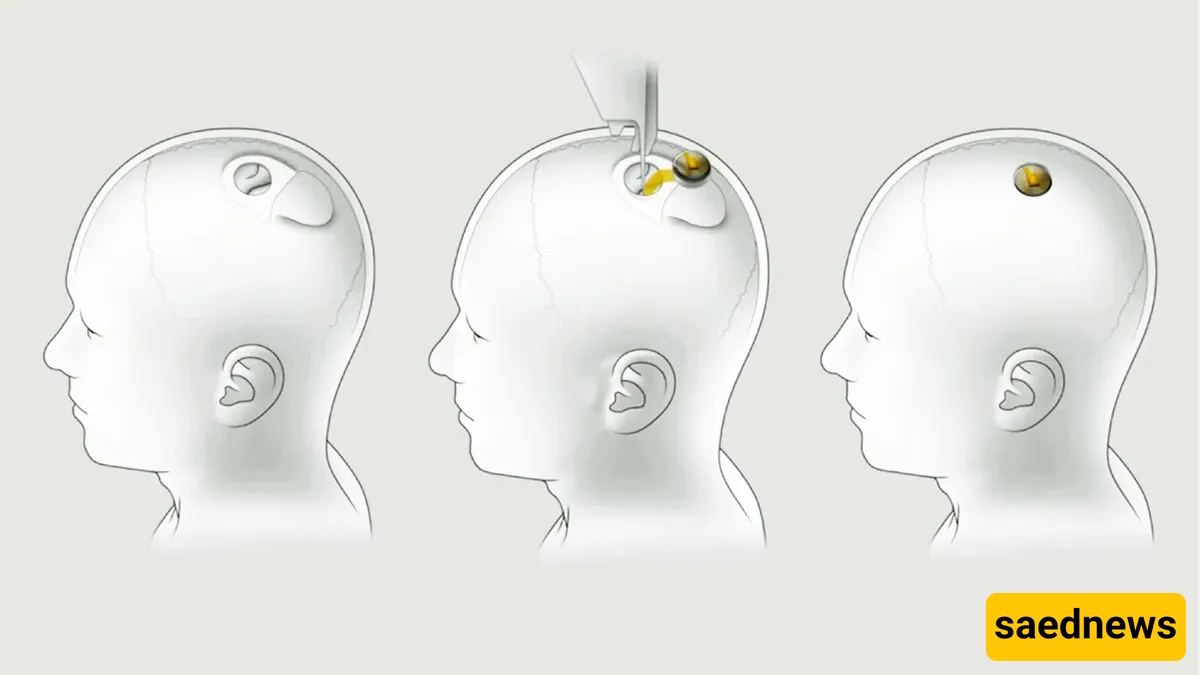

Neuralink’s system uses a slim “Link” chip and fleets of hair-thin electrode threads inserted into the cortex by a custom surgical robot. The aim: translate neuronal patterns into digital commands and, ultimately, restore function — for instance helping people with paralysis move cursors, operate phones or steer robots with their minds. Company demos and reporting show impressive demos: the second human recipient has reportedly used CAD software to design 3D objects and played video games at surprisingly competent levels.

That hardware-software combo is the reason the company draws both awe and alarm. If the threads can read reliably for years, the applications are transformational. If they don’t — or if they migrate, cause inflammation, or are hard to remove — the risks are medical and ethical. Regulators initially rejected Neuralink’s trial plans in 2022 citing safety concerns, later allowing human studies after changes.

Neuralink’s story reads like a tech comeback: an audacious private bet to commercialize decades of academic BCI research. Yet many neuroscientists remind viewers that similar building blocks existed in university labs long before Musk. Some experts praise the surgical-robot approach; others call the public spectacle “neuroscience theater” and warn against equating flashy demos with long-term clinical success. Recent long-form coverage traces the through-line from bench science to billionaire-run startup, and asks whether speed is trumping rigor.

There’s also a darker chapter: questions about Neuralink’s animal testing. Investigations and reporting have flagged monkey and other animal harms during rapid test cycles, prompting federal probes and sustained criticism from animal-welfare groups and some scientists. Those findings helped shape earlier regulatory pushback and still fuel skepticism about whether the company moved too quickly.

Concrete examples matter more than breathless futurism. Reported users with paralysis have demonstrated control of cursors and devices; one early recipient reportedly regained internet access and social connection after implantation. Another patient has been able to design a 3D part in CAD software and even play first-person-shooter games — milestones that show the tech can translate intention into action with usable fidelity, at least for now. These are medical outcomes that can change day-to-day life for people with spinal injuries or ALS.

Neuralink’s human trials started after a fraught path through regulators: an initial FDA rejection in 2022 was followed by eventual approval in 2023 after safety changes. The company has since raised large sums of funding and signalled plans to expand trials internationally, including clinical studies in the UK. That global push — and the promise of eventual projects like “Blindsight” (a visual prosthesis Neuralink has touted) — frames the firm’s ambitions as medical innovation plus a broad roadmap toward enhancement.

Not everyone is convinced this is the right speed. Independent researchers point out the longstanding technical challenges: chronic electrode stability, immune responses, safe explantation, and the gap between short-term demonstration and durable therapy. Wired, academic reviewers and neurologists have cautioned that while the robotic insertion and flexible probes are neat engineering, the fundamentals aren’t revolutionary enough to guarantee a smooth translation to mass therapy without careful, prolonged study.

One practical but profound question follows every BCI: once your neural signals become digital, who controls that stream? Companies, clinicians and regulators are racing to define privacy standards, consent norms and data governance for neural signals — and those policy frameworks currently lag the hardware. That gap matters if devices scale beyond therapy into elective cognitive enhancements or consumer products.