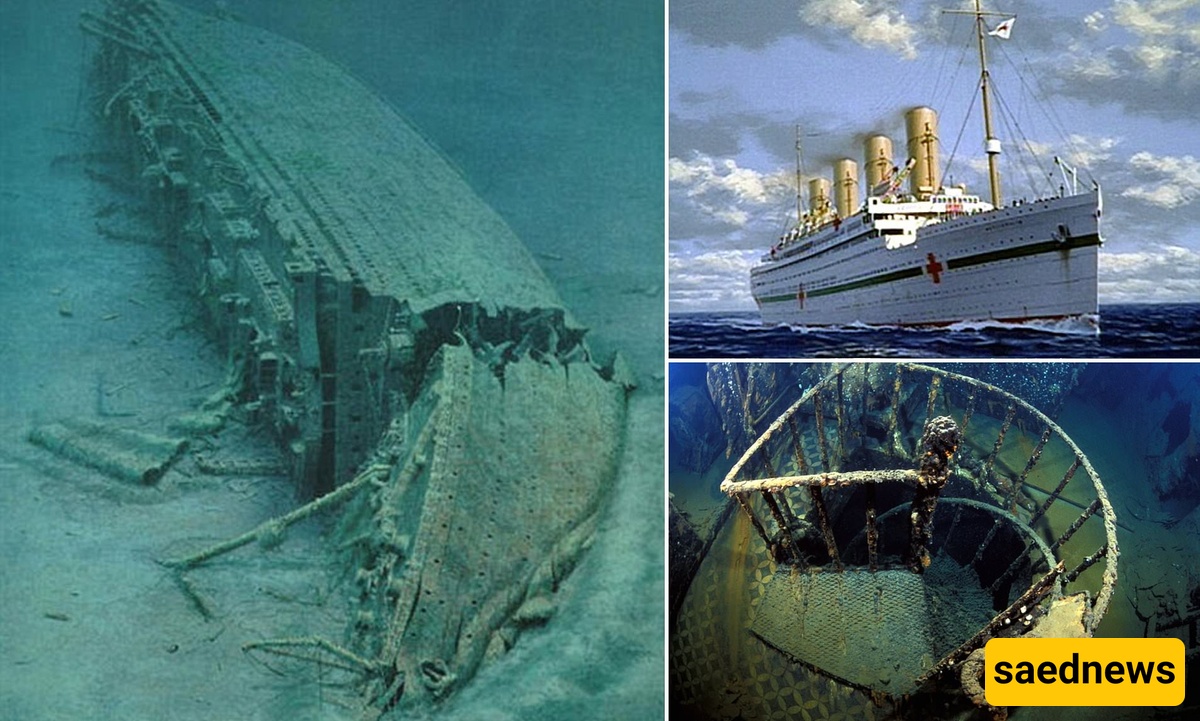

SAEDNEWS: Greece has unveiled artefacts recovered from the wreck of HMHS Britannic — the Titanic’s sister ship — more than a century after it sank during World War I. The discoveries, ranging from navigation lamps to a lookout bell, will soon be displayed in Greece’s new National Museum of Underwater Antiquities.

More than a century after its tragic sinking, the wreck of HMHS Britannic — the Titanic’s sister ship — has finally given up some of its long-lost secrets.

In a recovery operation quietly carried out in May and revealed this week, Greek authorities announced the retrieval of artefacts from the Britannic, which struck a German mine and went down in 1916 during World War I.

The mission, organized by British historian Simon Mills, founder of the Britannic Foundation, involved an elite 11-member team of deep-sea divers. Using advanced closed-circuit equipment, they ventured into the wreck resting off the island of Kea in the Aegean Sea, carefully lifting fragile relics from the seabed with air bags.

Among the treasures recovered were a ship’s lookout bell, a navigation lamp, a pair of binoculars, ceramic tiles from the vessel’s Turkish baths, and items from its first- and second-class cabins.

The artefacts, some astonishingly well-preserved after more than a century underwater, were immediately secured in containers, cleaned of marine organisms, and transferred to the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities in Athens. Conservation specialists are now working to ensure the items survive for public display.

However, not everything on the divers’ original list could be salvaged. Some objects were deemed too fragile or too inaccessible to recover safely.

Passenger observation binoculars were found and retrieved from the wreck site

A porcelain washbasin - full of marine organisms but intact - was found in one of the second-class cabins

The Britannic was the third and final ship in the White Star Line’s famous Olympic class, joining RMS Olympic and RMS Titanic.

Unlike its ill-fated sister Titanic, Britannic never served as a luxury liner in peacetime. Before it could set out on civilian voyages, the ship was requisitioned by the British Admiralty during World War I and converted into a hospital ship.

On November 16, 1916, while serving in this role, Britannic struck a German mine and sank in less than an hour. Of the 1,065 people on board, 30 lost their lives — many when lifeboats were pulled into the massive propellers as the ship went down.

Despite its size — Britannic was even larger than Titanic — the tragedy received far less attention, overshadowed by the Titanic disaster only four years earlier.

A diver photographs the wreckage of the HMHS Britannic during a recovery operation

The artefacts recovered this year will eventually go on display at Greece’s upcoming National Museum of Underwater Antiquities in Piraeus. They will feature in a dedicated World War I section, shedding light not only on the Britannic itself but also on the broader history of wartime naval operations in the Mediterranean.

For historians and maritime enthusiasts, the recovery is a major milestone. It highlights the importance of underwater archaeology in preserving fragments of human history that might otherwise be lost forever.

Simon Mills, who has dedicated much of his career to studying the Britannic, called the recovery “a dream fulfilled.” He emphasized that the finds will help connect future generations to one of the lesser-known but deeply significant maritime tragedies of the early 20th century.

While the Titanic continues to dominate cultural imagination through books, films, and exhibitions, Britannic’s story is only now beginning to resurface. The recovery of its artefacts ensures that this “forgotten sister” will finally claim its place in maritime history.

For Greece, the operation also underscores its growing role in underwater heritage preservation. With the establishment of the National Museum of Underwater Antiquities, the country aims to become a global leader in showcasing the hidden treasures of the seas.

Over a century later, the Britannic is still telling her story — one artefact at a time.