SAEDNEWS: Legends, ancient chronicles and modern tests all point to a frightening possibility: Qin Shi Huang’s burial chamber may contain booby traps and unusually high mercury levels. Those risks — plus the danger of irreparably damaging priceless artifacts — explain why archaeologists are still hesitant to open it.

There’s an ancient mound outside Xi’an that has refused to give up its greatest secret for more than two millennia. Beneath that innocuous hill sits the tomb of Qin Shi Huang, China’s first emperor — a subterranean world that classical historians painted as both wondrous and lethal. Today, those old warnings are amplified by hard science, producing a blend of archaeology and thriller that has left field teams cautious, curious — and more than a little unnerved.

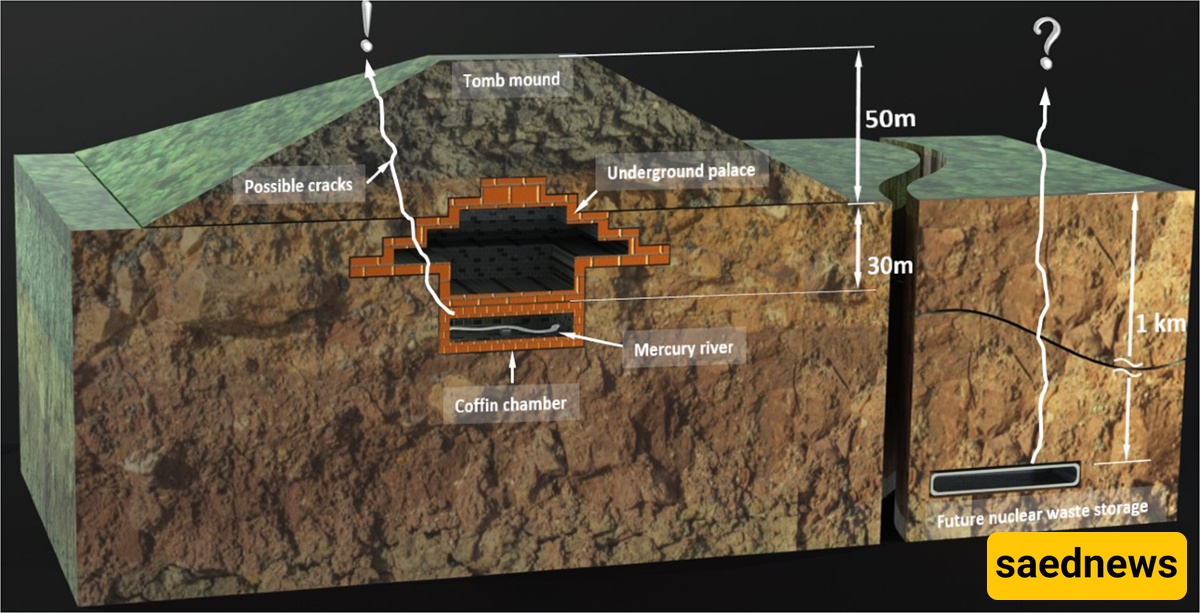

The earliest detailed description comes from the historian Sima Qian, writing a century after Qin’s death. His account portrays an underground palace laced with traps: mechanized waterways filled with mercury and crossbows primed to fire on intruders. For centuries scholars debated whether such images were grand metaphor or literal engineering — until modern surveys found something unsettling: unusually high mercury signals above the tomb mound. Those readings gave the old story a chilling new plausibility.

Mercury appears repeatedly in the emperor’s lore. Qin was reportedly obsessed with immortality and famously ingested mercury-laden elixirs; now scientists measuring atmospheric mercury above the mound have recorded elevated levels that line up with earlier soil tests. These measurements don’t prove a river of liquid mercury exists inside the burial chamber, but they do suggest significant mercury was used in the mausoleum’s construction — and that material could vaporize or migrate if the tomb is breached. That would create an immediate health risk for excavators and could spread contamination.

Even if toxic fumes aren’t the main worry, conservators fear irreversible damage. The terracotta warriors discovered nearby were once vividly painted; when exposed to air their pigments flaked and faded, leaving the grey statues we see today. Opening the sealed inner palace could expose delicate lacquer, textiles and organic materials to oxygen and microbes, starting chemical reactions that would permanently erase details no modern conservator could restore. In short: we could lose far more by opening the tomb than we might gain.

Recent scholarship has traced likely sources of the tomb’s mercury to nearby cinnabar (mercury-ore) deposits, explaining how enormous quantities could have been transported during construction. That finding helps explain the strong mercury signals — but it also underlines the scale of the problem: we might be dealing with tens of tons of toxic element sealed for centuries under pressure and humidity conditions we barely understand.Booby-trap fantasy — or ancient engineering?

The image of crossbows snapping and poison gas hissing feels cinematic, but experts caution against sensationalizing. Ancient engineers were capable of surprising mechanical tricks; whether those were actually installed as lethal defenses remains unproven. Yet the combination of textual warnings, credible mercury anomalies and the logistical difficulty of excavation forms a persuasive argument for caution. When the cost of a mistake is poisoning workers or destroying unique imperial art, “wait and study” becomes the responsible policy.

So what would it take to open the tomb safely? Many archaeologists say the answer is not brute force but patient, incremental investigation: non-invasive imaging, tiny robotic probes, climate-controlled micro-chambers and protocols derived from materials science. In other words, scholars want to reach into the emperor’s underground world with a glove on, not a crowbar. Until such techniques can guarantee safety and preservation, the mound will keep its secret — a dark, mercury-tinged heartbeat at the edge of history.