In Qajar Iran, diamonds, animal parts and ritual soups were more than curiosities — they were trusted “cures.” Welcome to a world where fear, faith and ignorance mixed into some of the strangest medical and social practices you’ll ever read about.

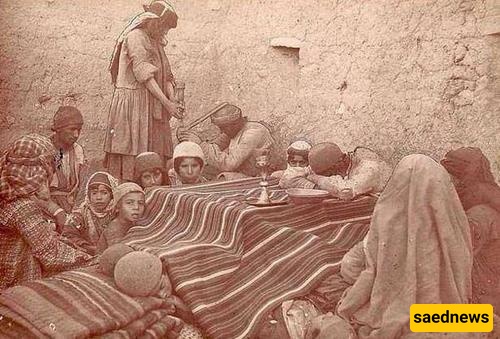

Superstition in Qajar-era Iran was widespread and socially accepted — not just among the rural poor, but inside palaces and harems. When modern medicine was scarce or distrusted, people turned to charms, talismans, divination and ritual remedies to explain and control illness, misfortune, jealousy and uncertainty. What looks absurd today often made practical sense then: when expertise, security and science were absent, symbolic acts offered comfort and a sense of control.

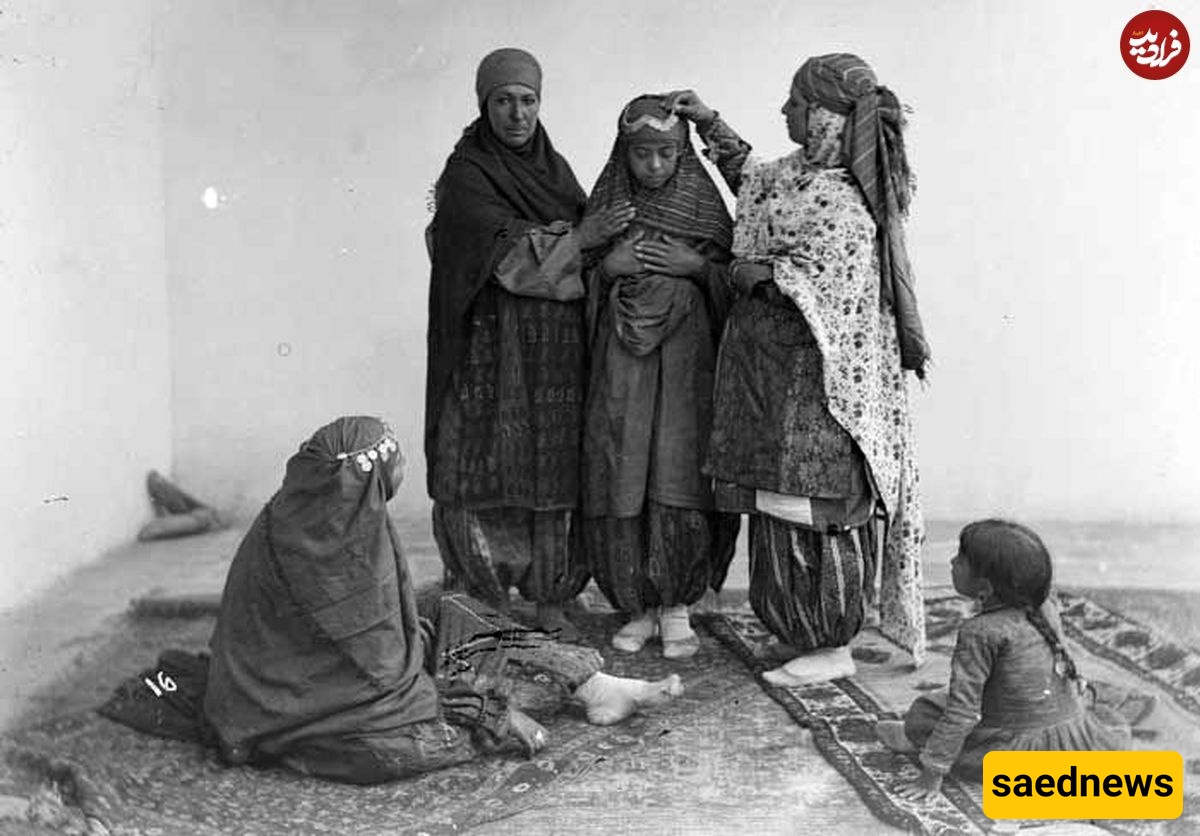

Professional charm-writers, fortune-tellers and certain religious figures (especially some dervishes and Jewish healers) were in high demand. They wrote talismans, sold amulets made from precious stones, animal parts and bits of cloth, and performed rituals that promised concrete benefits: better luck, protection from the “evil eye,” healed infertility, or even a painless death. Foreign observers recorded that women — including women of the court — were frequent clients, and authorities sometimes felt obliged to restrict visits (for example, banning women from going to some Jewish healers).

Contemporary memoirs and travel accounts list a bewildering inventory of “remedies”:

Animal parts: monkey liver, monkey heart, or monkey fat were reputed to grant charm and agility or inspire love; a hoopoe’s nail could be used to silence someone’s speech; wolf parts (and even “wolf venom”) were touted as fertility aids or protective substances.

Bat eye, ashes, powdered bones, and hair: each had its own magical use — inducing sleep, curing fits, or averting evil.

Stones and gems: pendants of certain gems were thought to strengthen the body or ward off seizures and pain. The royal treasure sometimes doubled as medicine: courtiers believed possessing a famous diamond could improve health and luck.

James Morier’s nineteenth-century travel notes (on Haji Baba’s world) exemplify the popular list of such items and their attributed powers.

Decisions about treatment were often made by divination rather than by clinical judgment. Methods included random draws from the Quran, counting beads on a rosary, or placing slips of paper inside holy books. A famous anecdote describes a practitioner named Mirza Jafar: after examining a patient he would take a long rosary, close his eyes, perform a divination, and ask whether he should give remedy A, remedy B, or remedy C — and only act if the auspice was favorable.

Astrology played a role too: if an astrologer declared a certain hour “inauspicious,” patients sometimes refused to take a physician’s prescription at that time.

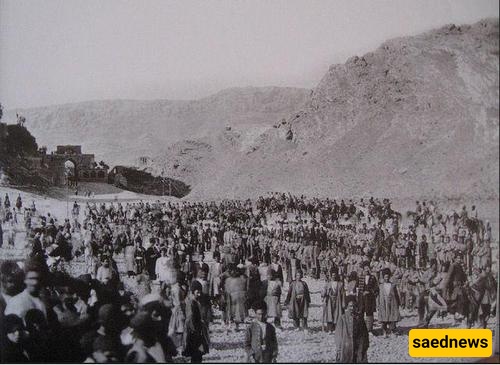

When epidemics struck, superstition often overwhelmed public-health sense. People relied on charms, prayers and secrecy rather than sanitation:

Rituals over hygiene: some believed that carrying or wearing a written charm or reciting special prayers would stop plague or cholera — and that naming the disease aloud was dangerous, so people avoided uttering its name in front of children.

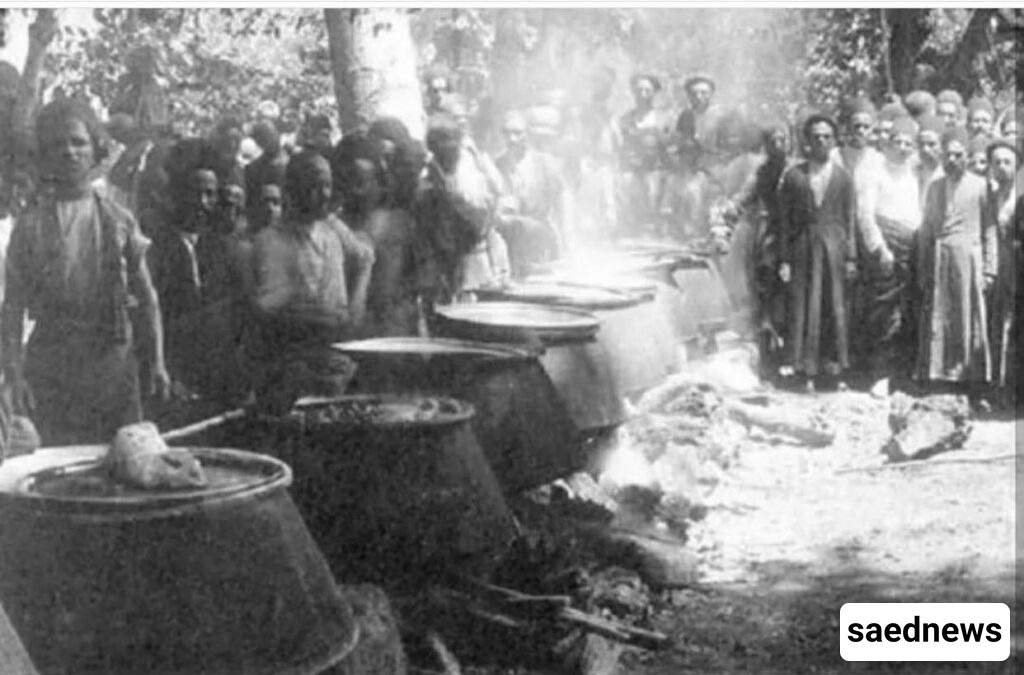

Royal remedies: Naser al-Din Shah reportedly ordered an annual preparation of a special soup thought to protect against cholera. The royal household also prized symbolic objects: foreign physicians recorded anecdotes of the shah showing a famed diamond (the Koh-i-Noor) as if it strengthened temperament and health.

Scapegoating and mistrust: foreign missionaries or non-Muslims were sometimes blamed for outbreaks, which fueled hostility and undermined cooperative public-health efforts.

These beliefs had real consequences: refusal to boil or treat water and reliance on “pure” running water or ritual cleansings helped spread enteric diseases.

Superstition could be weaponized. In the palace harem, magical remedies and rivalries sometimes turned lethal. Foreign medical reports from the period suggest at least one instance where a beloved prince died after receiving medicines or potions recommended by a charm-writer; afterward, gifts and letters poured into the court from women who had relied on those same intermediaries. The combination of secretive palace politics, women’s limited legal power, and belief in magical means made the harem a particularly dangerous place for intrigues dressed up as “remedies.”

Two broad causes explain the epidemic of unscientific practices:

Fear and social strain. War losses, foreign intervention, economic hardship, and authoritarian state power created chronic anxiety. When institutions fail, people turn to whatever reduces uncertainty — even charms and rituals.

Scientific illiteracy and restricted education. Low literacy rates and limited access to medical knowledge left many unable to evaluate competing claims. Women, who were often excluded from formal education and decision-making, were especially vulnerable to miracle cures and talismans as tools for survival, influence or solace.

Anthologists and social critics of the era linked women’s reliance on divination to their social marginalization: with few lawful means to secure status or protection, secret rituals and talismans became substitutes.

The Qajar period’s superstitions reveal not only ignorance but also how people made meaning under duress. Some practices were entirely destructive, others harmless rituals that offered emotional support. By the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, reformers and physicians began to challenge these beliefs, and as modern medical knowledge spread (unevenly), many of the era’s strangest cures slowly fell out of favor — though not always immediately.