SAEDNEWS: Abbas Abdi warns that without addressing the hardliner problem, rational policymaking in Iran is impossible. He describes them as a product of Ahmadinejadism, with pseudo-scientific mindsets, apocalyptic views, and entrenched crony influence in power structures.

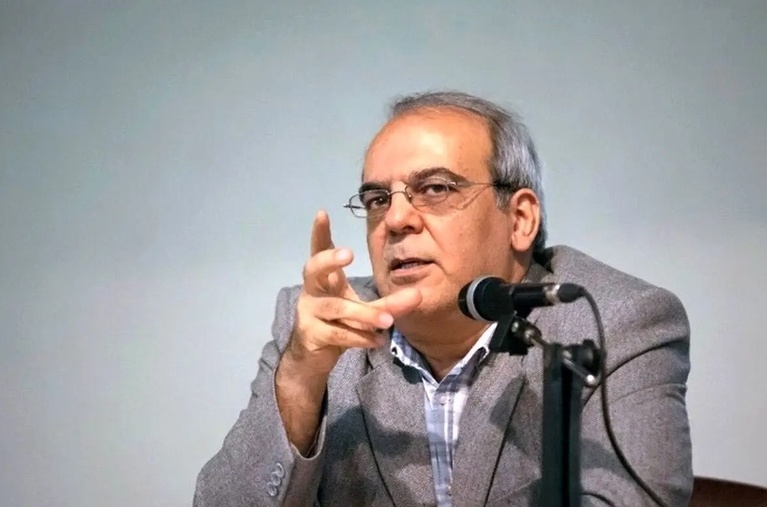

In an op-ed titled “The Hardliner Problem” in Etemad newspaper, Abbas Abdi wrote:

In Iran’s political arena, there is no issue more serious than the problem of hardliners. Without solving this issue, it is impossible for the country’s policymaking to follow a rational path. Of course, even in their absence this goal might not be achieved, but as long as they are embedded within the power structure, there will be no hope of resolving the country’s problems.

Hardliners are a force that emerged from “Ahmadinejadism” and the surge in oil revenues, possessing anti-scientific and pseudo-scientific mentalities. They often employ harsh, combative, and unrefined rhetoric. For them, religious beliefs are merely tools to achieve their ultimate goal — power. They do not shy away from lying and are miserly in telling the truth. They have no sense of responsibility, hold apocalyptic views, believe in astrology, prophecy, spirits, and talismans, and are deeply sectarian and stubborn.

These traits are not present in all of them to the same degree, but they are dominant characteristics of the group. They easily align themselves with special and exclusionary political agendas. Although their roots lie in conservatism, they view traditional conservatives as apostates from what they believe to be the true revolution and religion. Thus, their hostility toward traditional conservatives is no less than their hostility toward other political currents.

Contrary to their claims of religiosity, there is a deep rift between them and traditional religious communities. They instrumentalize religion and anything else in the name of what they call “revolution” and “justice-seeking.” They believe that by bestowing titles such as “martyr” or “martyr of honor” on certain individuals, they can exonerate and elevate them — not realizing that such usage strips these terms of their true meaning and leads people to sarcastically question, “So all martyrs are like Mr. Sedighi?”

They take no responsibility for their words or positions. They lack a grasp of large numbers, promising $11 billion in vegetable exports to Russia and single-digit inflation, yet doubling inflation in practice. They claim Iran’s economy will become the world’s second-largest, even as they push the economy and society down a steep slope. They promise to create jobs with one million tomans, but once in charge of job creation, they squander trillions with barely a few dozen jobs to show for it. They vow to destroy America, Israel, and others, yet when war breaks out, they boast merely that the enemy “failed to achieve its goal of toppling us.”

They once insisted the enemy would never dare to attack and that the probability of war was zero — then conveniently forgot these claims when conflict arose. They are obstinate in policymaking, as seen in disputes over daylight savings time, pro-natal policies, and internet regulations. They treat the government as personal property, appointing anyone they wish regardless of competence. They are obsessed with academic titles, attaching “doctor” to their names with fake degrees, even though their discourse is pseudo-scientific, anti-scientific, and apocalyptic.

Such figures exist in every society, even in the most developed countries. In the United States, about 30% of people believe in astrology and the influence of the stars on human life; roughly 15% deny climate change; at least 9% are conspiracy theorists; and, remarkably, at least 2% believe the Earth is definitely flat, with only 66% certain it is round — despite the fact that American astronauts have walked on the Moon. Meanwhile, 5% do not believe the Apollo 11 Moon landing ever happened.

Thus, supporters of such thinking are not scarce even in the United States — but there is one key difference: they hold no role within the power structure and have no means to enforce their beliefs through government policy. They remain merely a limited worldview with no connection to the state. In Iran, however, the situation is different.

One conservative activist told Ham-Mihan newspaper — in an effort to downplay concerns about these hardliners — that although he disagrees with their views, “they shouldn’t be silenced; they must be allowed to express their opinions.” This is true, Abdi notes, but the criticism is not about having such views.

The activist added: “Mr. X has opinions and expresses them, but he has no influence in managing the country’s affairs.” Here, Abdi disagrees: these individuals and their allies benefit unilaterally from the privileges of power and act accordingly. Merely expressing such opinions is not the problem — indeed, others voice similar ideas without issue. The problem lies in their privileged presence within the state apparatus and their use of its resources to advance their agenda. Having such beliefs in itself is not an issue — since they cannot think otherwise — but embedding those beliefs into governance is.