SAEDNEWS: Vampires didn’t start with Dracula — they’re rooted in thousands of years of myths, terrifying rulers, and even medical conditions. From Mesopotamian demons to Irish vampire kings, here’s the chilling evolution of the undead legend that still haunts us today.

Vampires are everywhere — from the glittering romance of Twilight to the gothic horror of Bram Stoker’s Dracula, these creatures have taken on countless forms in our imagination. But the truth is far darker: the vampire myth didn’t begin with literature. It stretches across thousands of years, dozens of cultures, and more than a few blood-soaked historical figures.

This is the story of how vampires evolved from terrifying folklore into one of pop culture’s most enduring obsessions.

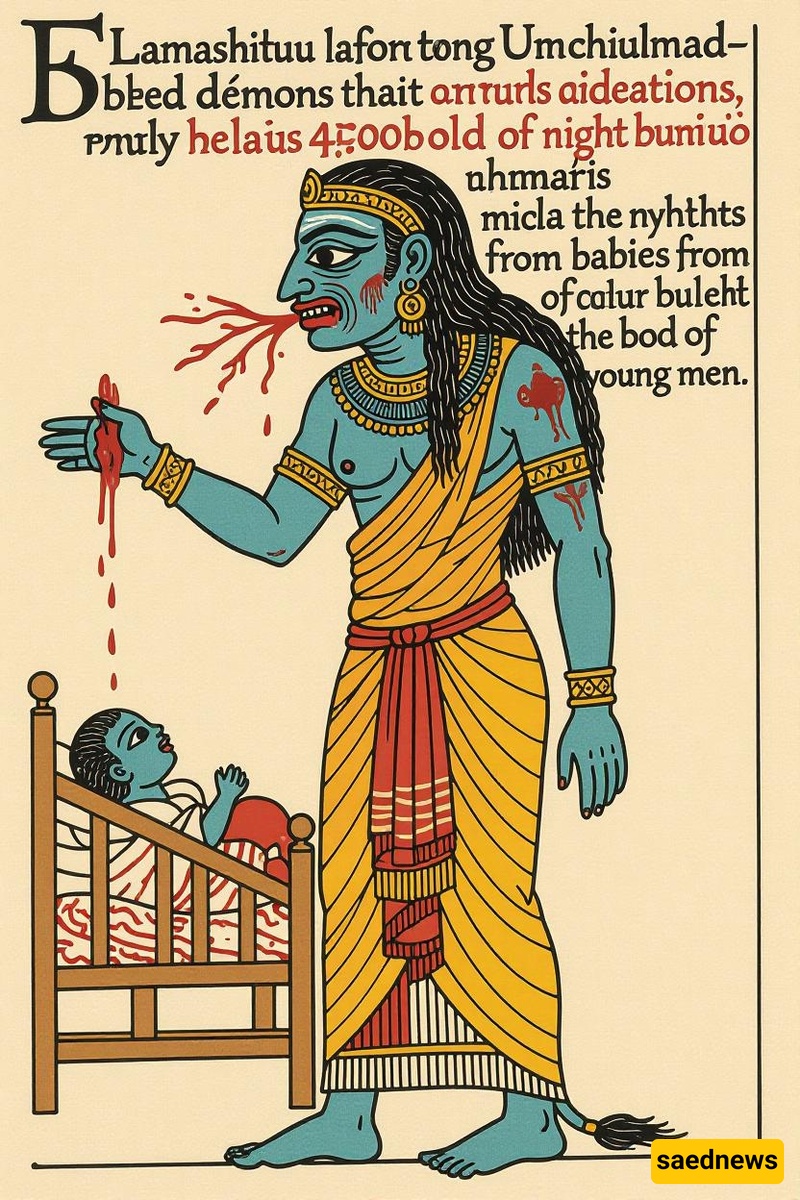

The idea of a blood-sucking, undead monster is at least 4,000 years old.

In Mesopotamia, people feared Lamastu, a night demon who stole babies from their cribs and drank the blood of young men.

In Jewish folklore, Lilith — Adam’s rebellious first wife — became a child-killing demoness who preyed on newborns and seduced men.

The Greeks had Lamia, cursed by Hera, who devoured children out of jealousy.

Across Asia, Chinese legends spoke of jiangshi, hopping corpses that drained the life force of the living.

These stories gave us the blueprint: vampires as twisted versions of human desires, combining lust, death, and blood.

By the Middle Ages, Eastern Europe had become the true home of vampire hysteria.

In Romania, people feared the Strigoi — restless spirits who returned to torment their families.

Villagers used brutal methods to “kill” them: staking, decapitation, or even burying bodies face-down so they would dig deeper into the earth instead of crawling out.

Obsessive myths even said vampires were compelled to count seeds scattered over their graves — a quirky detail that survives in folklore.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, paranoia exploded. Authorities dug up graves, staked corpses, and burned bodies across villages, spreading panic throughout Europe.

When Bram Stoker published Dracula in 1897, he drew on centuries of folklore — and more than a few horrifying historical figures:

Vlad the Impaler (1431–1476): A Wallachian prince infamous for impaling his enemies on stakes, sometimes while alive. Known as Dracula (“son of the dragon/devil”), he inspired Stoker’s vampire by name, if not in detail.

Elizabeth Báthory (1560–1614): Dubbed the “Blood Countess,” she allegedly tortured and killed hundreds of young girls, sometimes bathing in their blood to preserve her youth.

Abhartach, the Irish Vampire King: A dwarf chieftain in 5th-century Ireland who rose from the grave demanding bowls of blood until he was buried upside down under a heavy stone.

These chilling stories blur the line between myth and history.

Many assume vampires are a Transylvanian export, but Ireland might have played a bigger role than we think.

The legend of Abhartach circulated in Irish folklore for centuries.

Celtic festivals like Samhain (Halloween) were deeply tied to honoring the dead, strengthening connections between Ireland and the vampire myth.

Stoker, an Irishman himself, likely read these legends in Patrick Weston Joyce’s A History of Ireland before penning Dracula.

In other words, Dracula may have Irish blood.

Some vampire traits may have real-world roots:

Porphyria, a rare disease, causes severe sensitivity to sunlight and reddish teeth, eerily echoing vampire traits.

Catalepsy, linked to epilepsy and schizophrenia, could make someone appear dead while still alive — leading to premature burials.

Natural decomposition (swelling bodies, blood-like fluids, hair seeming to grow) also fed the vampire myth, terrifying those who opened graves.

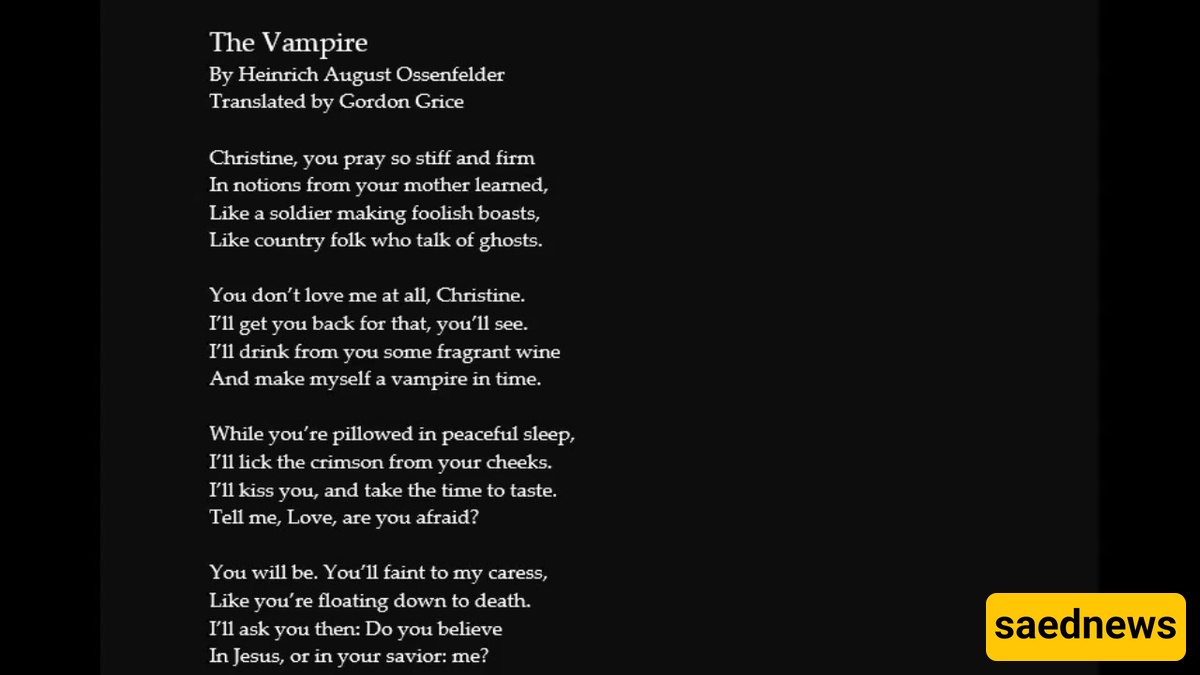

Bram Stoker wasn’t the first to write about vampires. He built on a growing literary trend:

“The Vampire” (1748) – a German poem by Heinrich Ossenfelder about lust and death.

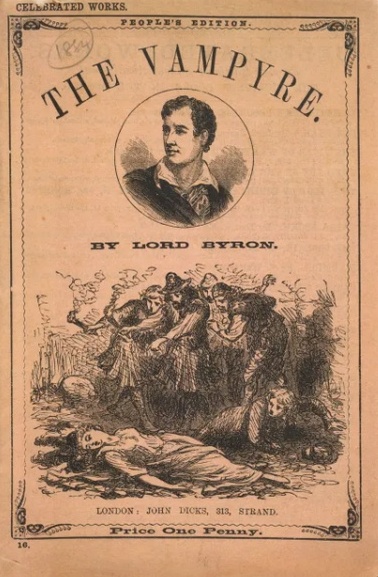

“The Vampyre” (1819) – John Polidori’s groundbreaking novella, inspired by Lord Byron, introduced the suave, aristocratic vampire.

Varney the Vampire (1845–47) – a serialized penny dreadful featuring a fanged vampire with super strength.

Carmilla (1871) – Joseph Sheridan Le Fanu’s novella about a female vampire and her lesbian undertones, a huge influence on Dracula.

Stoker combined these threads into one unforgettable monster.

From Nosferatu (1922) to Bela Lugosi’s Dracula (1931), from Anne Rice’s Interview with the Vampire (1976) to Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997) and even Twilight (2005), the vampire has shapeshifted with every generation.

Sometimes terrifying, sometimes sexy, sometimes sparkly — the vampire never really dies.

Vampires are more than just horror tropes. They embody our deepest fears:

Fear of death.

Fear of forbidden desire.

Fear of losing control.

From ancient demons to Netflix heartthrobs, vampires remain one of humanity’s most enduring monsters — because in them, we see the darkest reflections of ourselves.

So the next time you watch a vampire movie or joke about garlic, remember: the legend may be older, bloodier, and much closer to reality than you think.