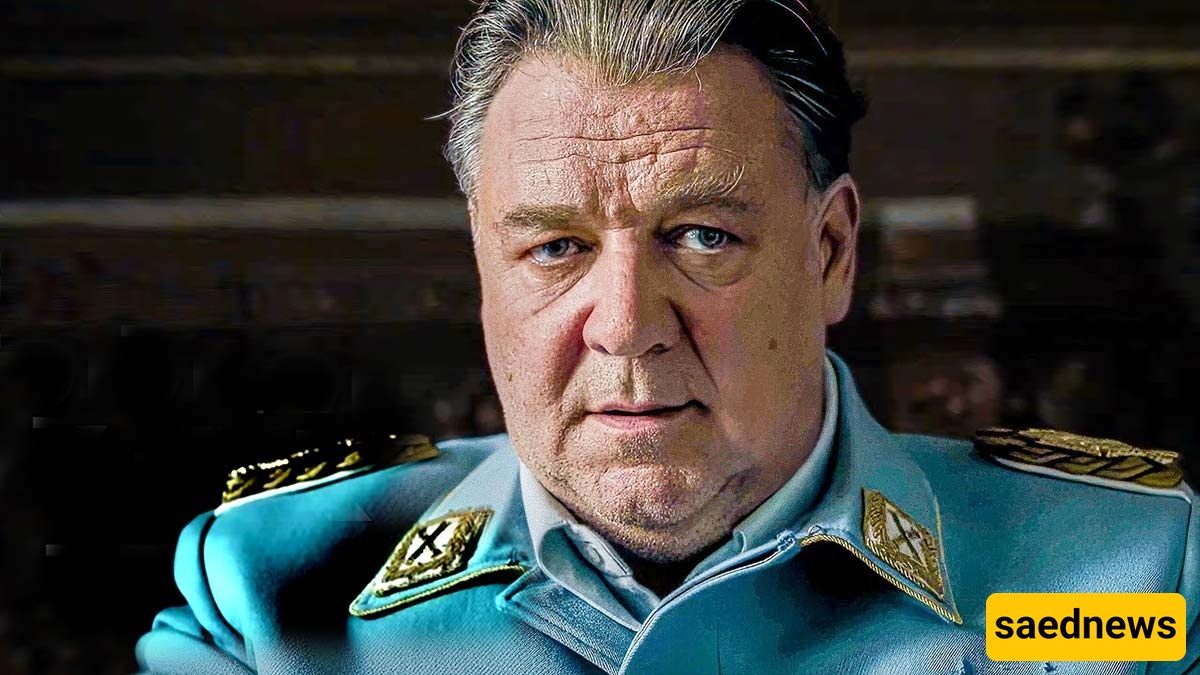

SAEDNEWS: The film ‘Nuremberg,’ featuring Russell Crowe as the second-in-command of the Nazi regime, is a movie crafted entirely with lavish studio sets and designed for the Oscars, showcasing Crowe delivering some of his finest acting.

Russell Crowe takes on the chilling role of a Nazi war criminal in Nuremberg, a film crafted in the classic, grandiose style of old Hollywood and designed for the Oscars. Directed by James Vanderbilt, the drama features Rami Malek as a psychiatrist who interrogates Hermann Göring but struggles to penetrate the Nazi leader’s formidable psyche.

At the heart of Nuremberg lies Crowe’s mesmerizing performance as Göring, Hitler’s second-in-command. Since his Oscar-winning turn in Ron Howard’s Cinderella Man (2005), Crowe hasn’t portrayed a character this commanding. With a powerful frame, meticulously styled hair, and a calm German accent that reflects his complete self-assurance, Crowe embodies a man capable of captivating audiences even as his crimes horrify the world. His performance perfectly captures the tension between Göring’s charisma and his monstrous deeds.

The story unfolds immediately after Germany’s defeat in World War II, as Göring and 21 other top Nazi leaders are transferred to a prison in Nuremberg to face the first international trial for crimes against humanity. Fully aware of the fate that awaits him—and the imminent death sentence—Göring maintains a calm demeanor. The film highlights the narcissism of Nazi leaders, who were so consumed by self-importance that it fueled their delusions. Göring, like Hitler, was addicted to drugs, consuming up to forty pills a day to mask his self-doubt.

In the military tribunal, American Colonel Douglas Kelley (Rami Malek), a psychiatrist, assesses whether Göring is fit to stand trial. From the very first moment, it is clear that he is. Kelley’s goal is to uncover Göring’s connection to his atrocities, yet the film intentionally restrains the depth of this exploration, focusing instead on the psychological interplay between interrogator and accused.

Crowe meticulously learned extensive German dialogue, initially maintaining Göring’s pretense of not understanding English. Ultimately, he drops the act, feigning ignorance of the ongoing events. He claims that the “labor camps” were merely camps and deflects responsibility to Heinrich Himmler, the third-in-command who orchestrated the Holocaust. Through calculated lies, Göring constructs a self-serving legal denial, showcasing the intricacies of moral and psychological manipulation.

Running two and a half hours, Nuremberg embodies the grandeur of a classic Oscar film, with lavish studio sets recreating bombed-out ruins and a courtroom in muted cream tones. The cast is filled with familiar faces portraying key historical figures. Vanderbilt, who also wrote the screenplay, demonstrates his narrative skill—having previously penned Zodiac and The Amazing Spider-Man—but the film stops short of fully capturing the psychological tension, instead forming an intellectual yet intimate bond between Göring and Kelley, reminiscent of Clarice Starling and Hannibal Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs. Crowe dominates every scene, deliberately keeping the audience at a measured distance.

The film doesn’t shy away from horror: archival footage and reconstructions show piles of corpses and skeletal remains, reminding viewers of the real human cost behind the courtroom drama. Michael Shannon delivers a powerful portrayal of Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson, while Richard E. Grant embodies British prosecutor Sir David Maxwell-Fyfe, ultimately sealing Göring’s fate with a single, piercing question: “Are you still loyal to Hitler?” Göring’s affirmative response confirms his sentence.

The core message of Nuremberg is clear: Nazis were not supernatural monsters—they were human. Unlike Jonathan Glazer’s The Zone of Interest, however, the film stops short of fully exploring the man behind the evil façade.

What makes Nuremberg particularly compelling today is its examination of justice. In a world where democratic institutions face unprecedented global challenges, the film confronts audiences with uncomfortable questions: How do societies respond to evil? Can justice ever be truly impartial?

Crowe’s brilliance lies in his refusal to take shortcuts in portraying Göring’s moral complexity. His performance reminds us that evil often wears a human face—it speaks fluently, persuades, and can even appear charming. Vanderbilt’s screenplay, based on Jack El-Hai’s The Nazi and the Psychiatrist, provides a sophisticated foundation for this nuanced portrayal.

Yet Crowe isn’t the only standout. Leo Woodall, known for White Lotus, delivers an emotionally resonant performance as a translator ensnared in the court’s machinery. Despite not knowing German before the role, Woodall brings restraint and depth, culminating in a late scene that moves viewers profoundly.

Given the Academy’s recent interest in historically significant, cautionary tales such as Oppenheimer and The Trial of the Chicago 7, Nuremberg is already a strong contender for Best Picture consideration.

The film’s timing is particularly poignant. As democracies face internal threats and international law grapples with new forms of warfare and authoritarian manipulation, Nuremberg offers a historical lens with urgent relevance today. It is a film about the past, yet its message resonates powerfully in the present.