SAEDNEWS: The introduction of electricity to Iran was made possible through the efforts of a well-known Isfahani merchant, Hajj Hassan Amin al-Zarb. He had close ties with the Qajar king and, during a trip to Russia, brought an electricity factory back to the country with him, along with the royal entourage.

According to SAEDNEWS, Abdollah Mostofi writes in his book The Story of My Life that "At this time, the streets did not have public lights. Only the wealthy would install a lamp connected to the wall at the entrance of their homes. Therefore, lanterns and lantern-bearers were essential parts of daily life. The grandeur of these lanterns, whose cylindrical diameter sometimes reached half a meter and height about a yard, reflected the social status of their owners. There was no official standard or rule for the size of the lanterns relative to the rank of their owners, but people of that era, particularly the ones who held important positions, would never go beyond their limits and show off a larger lantern than necessary."

The introduction of the electricity factory to Iran was made possible by the efforts of the well-known Isfahani merchant Hajj Hassan Amin al-Zarb. He had close ties with the Qajar king and, during a trip to Russia, brought the electricity factory back to Iran, an event which astonished the capital's residents. Ja'far Shari writes in his book Old Tehran, "Amin al-Zarb's factory was one of the wonders that continued to astonish the people of the city for years. Every evening, they would gather to watch it, marveling at the sight for a long time, biting their lips in amazement and exclaiming 'La hawla' (an expression of astonishment)."

However, despite the fascination with the lights, the people showed little interest in using it, and the only benefit from the factory was the few lights illuminating the streets around the royal palace. The lights were only lit at dusk and were turned off by the end of the night. The cost of the lighting varied: forty candles for four shahis, seventy-five watts for seven shahis, and one hundred candles for ten shahis. Some merchants would use tricks, installing low-wattage bulbs at first and then switching to higher-wattage bulbs after the inspector had passed.

The development of electricity and lighting did not spread quickly across Iran. For many years, Tehran’s streets continued to be illuminated by traditional lanterns, even after the efforts of Hajj Hassan Amin al-Zarb. Ja'far Shari notes, "Before the coup of 1299 and the premiership of Seyyed Zia' al-Din Tabatabai, if any light appeared in the streets at night, it was from the few lamps placed near the royal palace, casting a dim glow, while the rest of the city was immersed in complete darkness. Even those few lamps, hanging from their wires and swaying, were often destroyed by stones and slingshots from children."

Among the reforms introduced by Seyyed Zia' al-Din was the effort to provide lighting for the rest of the city. This was done by purchasing green tin lanterns with glass on three sides and a vented cap. These lanterns were mounted on iron stands and fixed to the walls every fifty steps, each requiring five seer of oil per lantern, with a lamp keeper assigned to every one hundred and fifty lamps. This brought a minimal level of lighting to the city's streets.

However, the government could not provide the electricity needed for Tehran on its own. This led the members of the National Assembly, after the fall of the Qajar dynasty, to suggest that electricity production be privatized. Abbas Masoudi, the editor of Ettela'at newspaper, describes the situation in his book In a Quarter-Century: "Tehran’s electricity was limited to the factory of the late Hajj Amin al-Zarb, located on the street of Chahargah. A bill had been submitted to the parliament regarding the electricity factory’s monopoly, but Mr. Hajj Seyyed Reza Firouzabadi disagreed and believed that electricity should be made available to everyone and that if this were done, more people would accept it and the electricity would expand."

"After more than twenty years, in 1325, we realize that Mr. Firouzabadi’s opinion was correct, and complete freedom should have been granted for public facilities. If the issue of monopolies and concessions had not existed, and if the government had not restricted electricity to the municipality or handed it over to national companies, today, Tehran’s electricity situation would not be so unfortunate, where electricity is still bought and sold on the black market, and people continue to suffer."

The darkness of Tehran’s streets, years after the introduction of electricity, was so problematic that Ettela'at newspaper, in an article from 1307, referred to Tehran as the "City of the Silent". The article states: "The capital of Iran, which goes dark at midnight, should be called the city of the silent. Electricity is turned on at dusk and cut off at midnight, meaning Tehran has electricity for only four or five hours, and after midnight, the city falls into complete darkness, making it a place for accidents and crimes. The death of the late Darvish Alam, a famous musician, due to the darkness of the night has not been forgotten."

The introduction of electricity to Iran occurred during the reign of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar, in the mid-Qajar era.

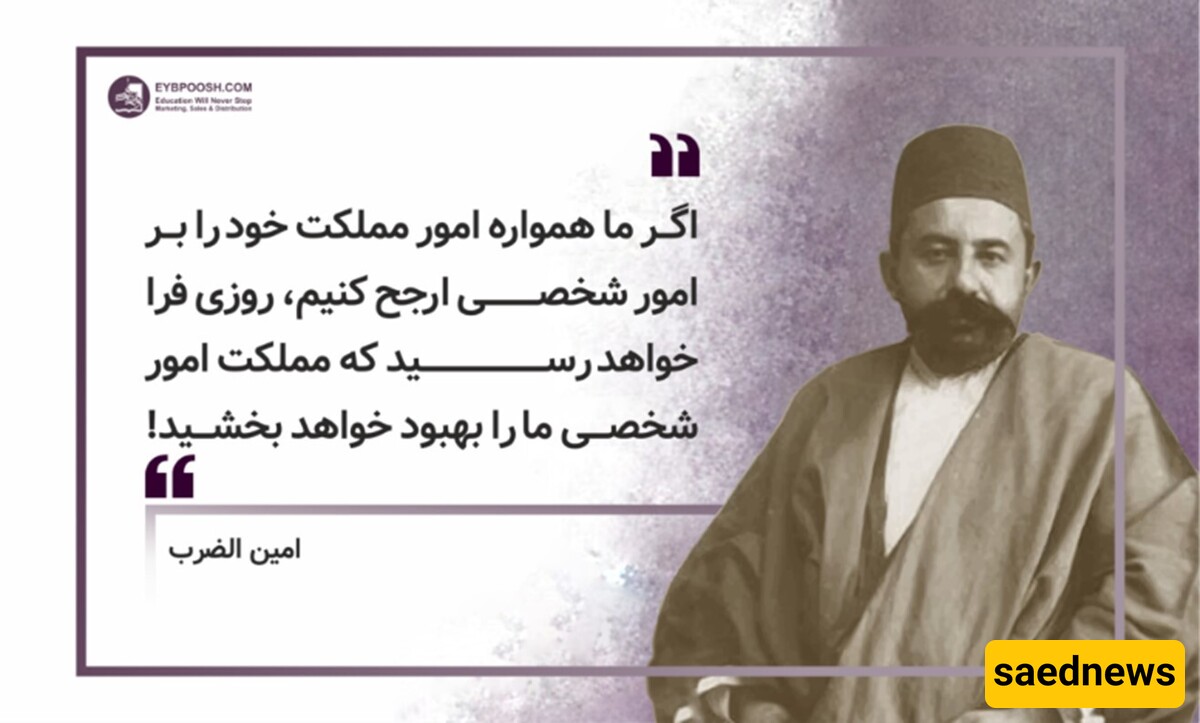

The introduction of the electricity factory to Iran was achieved by the efforts of Hajj Hassan Amin al-Zarb, a well-known Isfahani merchant. Who was he? Pages of Iranian history speak well of this industrious merchant from the Qajar era. "Hajj Mohammad Hassan Amin al-Zarb, later known as Amin al-Dar al-Zarb, was an intelligent and prominent merchant of the 19th century," and one of the leading industrial investors in Iran.

Mirza Hassan, when he left Isfahan for Tehran in his youth, had very little capital. His son wrote, "When Amin al-Zarb arrived in Tehran around 1853, his worldly possessions included a cloak, an abacus, and 100 rials." His cousin later wrote, "His initial assets were 26 tomans in cash and a donkey." However, fate soon showed its favorable side to Mirza Hassan, and he reached a position where Naser al-Din Shah remarked, "Hajj Mohammad Hassan Amin al-Zarb is truly our personal merchant [and responsible for managing] factories and acquiring some goods from foreign countries."

Amin al-Zarb, who was "cunning, intelligent, and hardworking," soon rose through the ranks, and in addition to his personal businesses, became the head of the royal mint due to his closeness to the royal court, earning the title of Amin al-Zarb, which was later passed down to his son, Mirza Hussein. During religious festivals or mourning ceremonies, Amin al-Zarb would open his home to the needy, offering hospitality, especially during the month of Muharram. According to his son, during these times, around 3,000 men and women would be fed by cooking two to three tons of rice daily. "Even in normal times, his home was frequented by scholars and religious figures."

Amin al-Zarb, along with his son, became renowned not only for their wealth and trade but also for their integrity and care for the people. He helped the scholar Seyyed Jamal in Russia when the Shah had exiled him from Iran. Amin al-Zarb believed that Seyyed Jamal was a true spiritual leader dedicated to advancing Islam.

Amin al-Zarb, following his progressive and helpful ideas, contributed to various industrial and developmental projects, including the construction of a railway between Mahmoudabad and Amol, the establishment of an electricity factory, a glass factory, a porcelain factory in Tehran, a silk spinning and weaving factory, and the building of the Hassanabad inn on the Tehran-Qom road. He also proposed the creation of Iran’s first steel factory in 1304 AH, for which he obtained the concession from the Shah but was unable to execute. One of his most notable acts was purchasing large amounts of wheat during the famine of 1288 AH from Mazandaran and transporting it to Tehran, saving the people from certain death.