SAEDNEWS: We are so captivated by the idea of bringing the dead back to life that we must ask—could science actually enter this realm and make it a reality? On one hand, the idea seems absurd; naturally, the dead cannot return to life. But consider this: Lauren Kanady was clinically dead for 24 minutes before being brought back to life.

According to SAEDNEWS, quoting Gadget News, reviving the dead remains one of today's most controversial questions. Various scientific ideas have been proposed to reverse death, which you can explore below. If you’ve never watched a zombie movie, you might actually be living in some strange interdimensional bubble. Whether or not you enjoy this genre, you should at least be familiar with zombie stories and their basic principles.

Since the first "Living Dead" film, zombies have explosively dominated cinema screens, portrayed as the result of plagues, fungi, alien influences, or even without any clear explanation. This genre has grown into a multi-billion-dollar industry—but how does it hold up in reality?

Will Humans Ultimately Outsmart Death?

We are so captivated by the idea of resurrecting the dead that it begs the question: is there an opportunity for science to delve into this realm and make it a reality? On the surface, the idea seems absurd—dead people cannot come back to life. Yet consider the case of Lauren Canaday, who was clinically dead for 24 minutes before returning to life. Some people have survived as long as 27 minutes without a heartbeat.

These cases should not be confused with the “Lazarus effect,” which creates the impression that someone has died and then revived. The examples above refer to genuine clinical death, followed by revival. Does it matter that the time frame was less than half an hour? What if we could extend this time? Could we come back from death—not as zombies, but as ourselves, with minimal side effects? Medical science holds some clues about whether reviving the dead is truly possible.

Carol Brothers suffered cardiac arrest, and 30 to 45 minutes later, her heart spontaneously began beating again. Others have also come back to life hours after cardiac arrest. Typically, the Lazarus effect occurs about 10 minutes after a person is declared dead. This means the heart stops, CPR is initiated, death is declared, and CPR is halted. But 10 minutes later, the person may spontaneously revive.

It’s important to note that the Lazarus effect does not equate to resurrecting the dead. Being declared clinically dead does not mean a person is truly dead—it simply means no vital signs are detectable. Blood flow to the brain and body is delayed, not permanently halted, though the reasons for this phenomenon remain unclear.

This distinction is critical because it suggests that some individuals might be wrongly declared dead when they could still be saved. Under normal circumstances, only a few minutes exist to save a life. The brain requires oxygen and blood flow; after 5–10 minutes without breathing, irreversible brain damage is highly likely. Beyond 15 minutes, survival is nearly impossible.

Death occurs in stages, and we already have interventions, such as CPR, to delay its effects. These methods can extend life beyond points where death would otherwise be inevitable.

One promising technique is therapeutic hypothermia, sometimes used for cardiac arrest patients. Hypothermia preserves brain function and increases the likelihood of survival. While low temperatures are typically harmful, induced hypothermia after cardiac arrest protects tissues until normal blood flow resumes, minimizing long-term or irreversible damage.

Scientists are also exploring experimental methods to reverse death entirely while preventing certain types of damage.

Cryonics (or cryopreservation) is one such field. The baseball player Ted Williams had his head surgically removed and cryogenically frozen in 2002. The idea is that future advancements could reverse death and restore life.

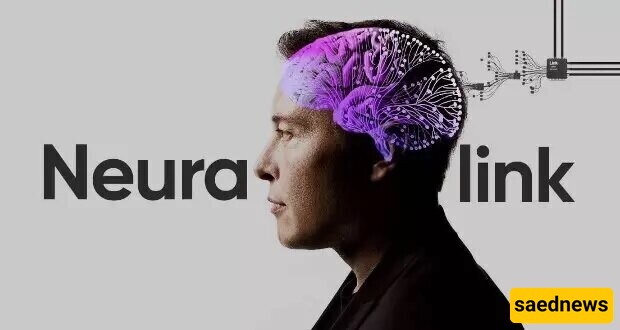

Companies like Tomorrow BioStasis now offer cryopreservation services, primarily to tech enthusiasts who can afford to preserve their brains after death. The hope is that future technology will either repair the cause of death or upload the preserved mind into a new body—or even into a virtual environment.

In 2016, BioQuark proposed experiments involving stem cell injections into the spinal cords of brain-dead patients, combined with nerve stimulation and protein treatments. Although the idea faced sharp criticism, it highlighted a willingness to push boundaries in the quest to overcome death.

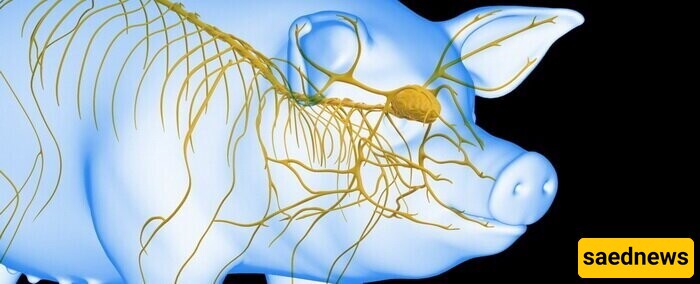

In 2019, Yale researchers restored some cellular activity in a pig's brain four hours after its death. They observed blood circulation and cellular function but stopped short of actual revival. This experiment challenged longstanding beliefs about the limits of brain death, showing that brain cells can survive longer than previously thought.

A similar study in 2022 involved circulating blood-like solutions through a pig's body, which led to signs of tissue repair in organs that had been dead for hours. Again, no awareness or consciousness was observed, but it raised ethical questions about the boundaries between life and death.

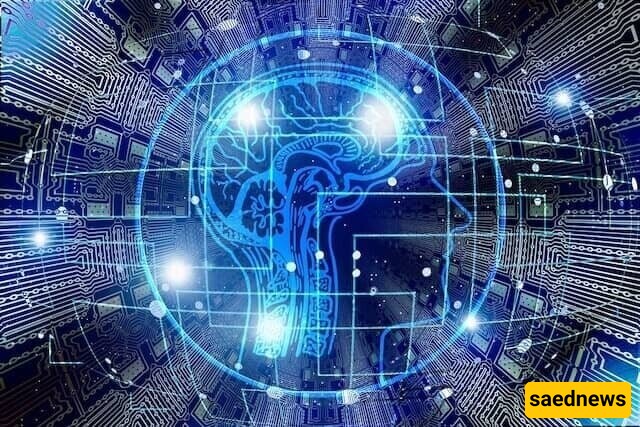

A more futuristic possibility for defeating death lies in digitizing the human mind. This concept relies on advanced computational methods to store a person's entire consciousness in a machine, bypassing the need for a physical body.

Science fiction has long entertained this idea, and futurist Ray Kurzweil predicts it might become a reality by 2045. The human brain, estimated to have 2.5 petabytes of memory, could theoretically be replicated using massive storage systems.

However, the challenge lies in replicating the complexity of the brain’s 125 trillion synapses and the chemical and hormonal interplay that defines personality and consciousness. A digital mind without access to a body may lack the essence of being truly "human."

The ethical implications of digital immortality are profound. Imagine being revived in a virtual world centuries from now, dependent on those who control the hardware housing your consciousness. Without a body, autonomy might be impossible, and the experience could be isolating or even dystopian.

Even if feasible, does uploading a mind equate to true immortality? Would a digital copy of your mind still be "you"? These questions, for now, remain philosophical.

While the concept of resurrecting the dead through cryonics, biological methods, or digital replication remains theoretical, advancements in medical science may eventually blur the line between life and death. If digital immortality becomes achievable, it could render other methods of revival obsolete. For now, these possibilities spark both awe and caution, forcing us to confront our deepest fears and hopes about mortality.