SAEDNEWS: In a potential breakthrough for reviving stalled nuclear diplomacy, Iran has signaled readiness to transfer its stockpiles of highly enriched uranium abroad — in exchange for yellowcake — under the framework of a new agreement.

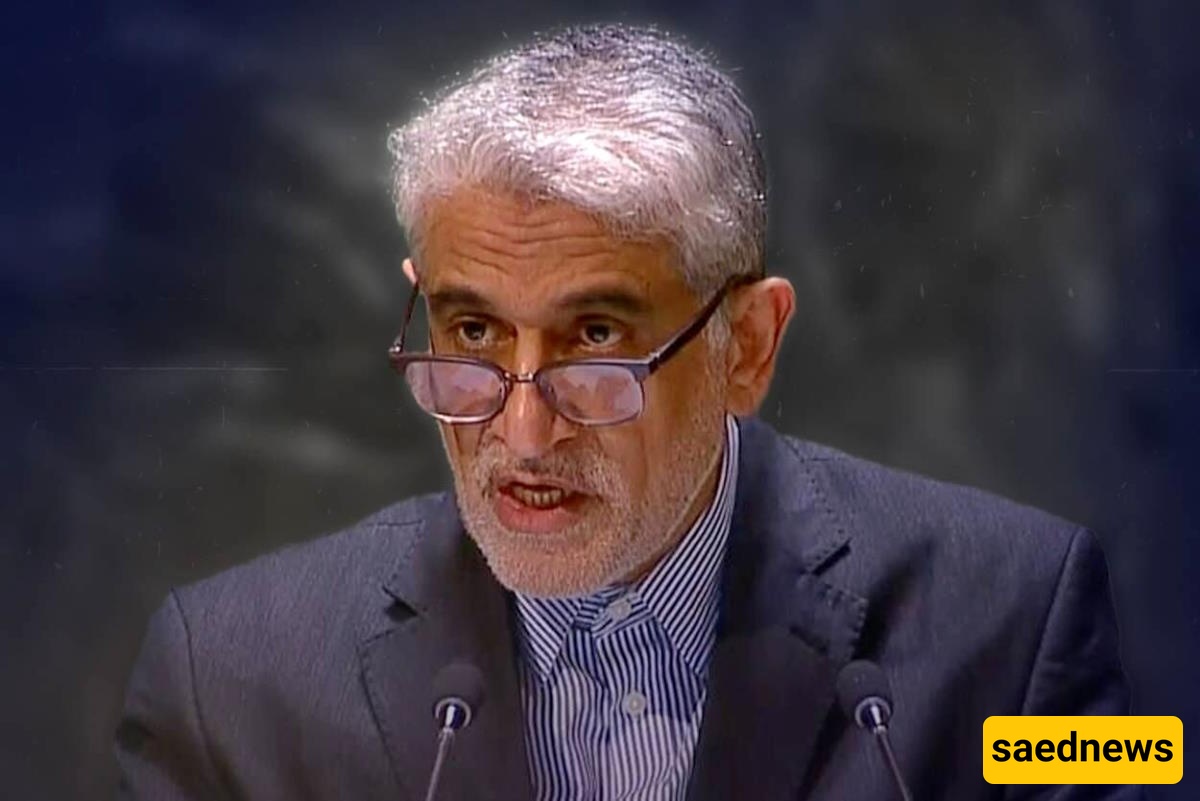

According to Saed News, Iran has floated a new proposal aimed at easing international concerns over its nuclear programme. In a rare on-the-record interview with Al-Monitor, Saeed Iravani, Iran’s ambassador to the United Nations, outlined Tehran’s conditional readiness to export its 20% and 60% enriched uranium stockpiles in exchange for yellowcake, a lightly processed form of uranium used as nuclear reactor fuel.

“If a new agreement is reached,” Iravani stated, “we are prepared to remove our enriched uranium stockpiles from Iranian territory, just as we did under the JCPOA [Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action] in exchange for yellowcake. Alternatively, these reserves could remain inside Iran under IAEA seal.”

The remarks, first published by ISNA and picked up by Iranian media, represent a rare diplomatic overture amid years of stagnation in nuclear talks. The offer echoes a prior JCPOA mechanism in which Iran shipped uranium to Russia under international supervision in 2015. However, any such move now would require a new consensus — not only among the original deal’s signatories but also in the broader context of regional and transatlantic tensions.

Despite this olive branch, Iravani was unequivocal on two key points: Iran will not accept any restrictions on its missile programme, and domestic enrichment remains non-negotiable. “We insist that enrichment must take place on Iranian soil,” he said, rejecting suggestions that regional consortia or external partnerships could replace Iran’s internal nuclear infrastructure.

Still, the ambassador struck a conciliatory tone on regional collaboration. He expressed Iran’s willingness to cooperate with neighboring countries operating nuclear reactors in areas such as safety protocols and fuel management. While endorsing the idea of a regional enrichment consortium as a possible supplement, he reiterated that it could not substitute for Iran’s sovereign programme.

Iran’s messaging appears calibrated: asserting national rights under the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) while leaving room for diplomatic maneuvering. Iravani stressed that Iran seeks nothing beyond what is legally entitled to any NPT signatory: “We want neither more nor less than the rights accorded to other members — namely, to research, produce, and utilize nuclear energy for peaceful purposes.”

The timing of this proposal is notable. With tensions still simmering over Iran’s ballistic missile tests, proxy engagements across the Middle East, and renewed Western scrutiny over uranium enrichment levels, Tehran may be seeking to preempt further escalation or sanctions through strategic flexibility.

Yet skepticism abounds. Washington and European capitals remain wary of what they view as Iran’s incremental nuclear advances and diminished transparency. A new agreement — particularly one replicating the mechanisms of the JCPOA — would face not only diplomatic but also political hurdles, especially in an American election year and amid Israel’s growing alarm.

Still, Tehran’s conditional offer to part with its most sensitive nuclear material suggests that the door to diplomacy remains ajar. Whether the West chooses to walk through it may depend less on trust than on what both sides perceive as the cost of continued deadlock.