The first time the term HPV was introduced was in 2018 during the Maah Asal TV program by “Yasi,” or more formally, “Yasaman Ashki.” Yasaman Ashki appeared on the show and announced the outbreak of a deadly disease, claiming that the solution was the injection of a vaccine.

According to the Science and Technology Department of Saad News, quoting Farhikhtegan, Yasaman Ashki stated during a live television broadcast that funding needed to be gathered for the production of the vaccine since it was imported, and the budget required to produce it domestically was something the government was unable to provide at that time. Now, nearly six years later, the name HPV has resurfaced in public discussions. Nowadays, almost every medical blogger, pharmaceutical blogger, and even midwives are creating content on Instagram about HPV, its dangers, and the need for the Gardasil vaccine. They believe that anyone eligible for the vaccine should buy and inject the foreign Gardasil vaccine. One could say an HPV panic wave has emerged in society, with the stakeholders profiting from the fear that was initially planted six years ago.

Yasaman Ashki and the “Rah” Association were the pioneers of the HPV vaccine project. She appeared on Maah Asal, discussing the dangers of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and their complications, including cervical cancer. She claimed that in the next 10 years, a dangerous wave of these diseases would threaten Iranian women and mothers. She advocated for Iranian children to receive the vaccine to prevent the virus. She was introduced as an active figure in the field of social issues during this program, and she called for financial support from the public. After this broadcast, Ashki revealed in an interview with Mashregh that the Minister of Health at the time had supported the project and personally requested her appearance on the show. She further disclosed that a memorandum of understanding had been signed between the “Rah” Association, which she manages, and the Ministry of Health’s social affairs department. Under this memorandum, Ashki was tasked with promoting and collecting funds for the HPV vaccine—specifically, the vaccine which would eventually be produced domestically with lower capacities.

HPV has around 200 different types, categorized as either high-risk or low-risk. It is a common sexually transmitted virus with various transmission methods. One of the established transmission methods, according to scientific literature, is sexual intercourse. However, some experts suggest that due to the high transmission rate, it could also be contracted from the environment or even by skin-to-skin contact with an infected person. One gynecologist stated in an interview with Farhikhtegan that while it is possible for someone to contract HPV during their life, contrary to the HPV panic created in society and by those promoting vaccination, the body’s immune system may fight off the virus without the individual even realizing they have it.

The Iranian HPV Association has reported that “according to studies, the prevalence of HPV in Iranian women is 23%. The highest and lowest prevalence rates were observed in Tehran and Isfahan, at 97% and 2.2%, respectively. Furthermore, there has been a significant increase in HPV68, which is rarely reported in Iran. These findings should be seen as a wake-up call for relevant authorities, stressing the importance of educational programs in high schools and appropriate vaccination in Iran.” However, despite warnings from non-specialists about the increasing HPV prevalence in recent years, no official figures have been released by the Ministry of Health on the actual rate of infection in the Iranian population. “No official statistics on HPV infection in Iran have been available since 2019, and because of the lack of data collection, our country's authorities have not provided any figures to international organizations related to the issue,” said Hadi Yazdani, a young doctor researching HPV in an interview with Farhikhtegan. This raises serious questions about the data used by certain experts and doctors to continuously instill fear in the public about HPV and even claim that HPV could be contracted by simply visiting a public pool or restroom. The real question is whether the demand for the HPV vaccine is based on genuine needs or if it is being artificially created by stakeholders through HPV hysteria.

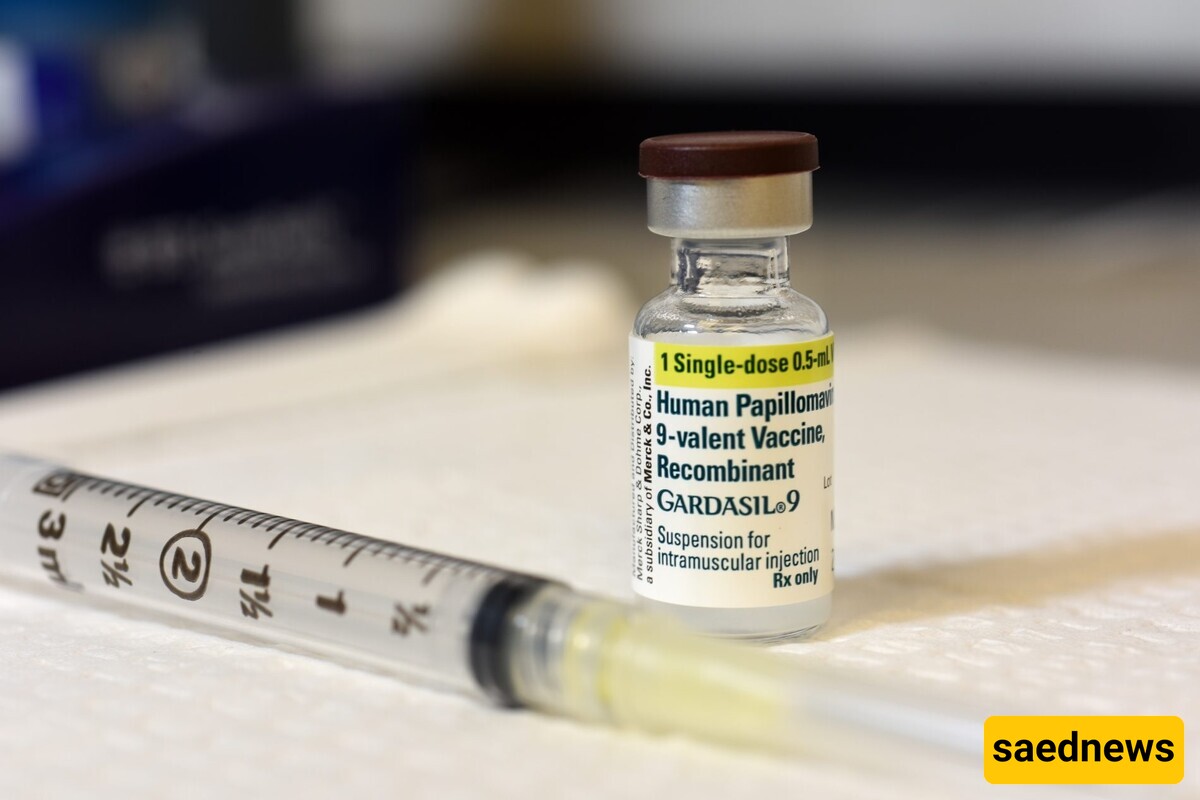

Gardasil is a popular HPV vaccine. It has been available for several years and is said to prevent diseases like genital warts and various cancers, including cervical cancer. Gardasil is produced in countries like the United States, the Netherlands, and Switzerland. Notably, Gardasil has a specific timeline for administration, and is typically administered to teenagers aged 15 to young adults up to 27 years old in many countries. For those already infected with HPV, the vaccine does not treat genital warts but can prevent infection from other types of the virus. Gardasil is generally available in both 4-valent and 9-valent versions, with the 4-valent vaccine covering four common HPV types and the 9-valent covering nine.

The Iranian HPV vaccine, known as Papilloguard, is a 3-valent vaccine focusing on preventing cervical cancer after HPV infection. Both the 4-valent and 9-valent Gardasil vaccines, as well as the Iranian Papilloguard, require three doses to establish immunity.

Undoubtedly, prevention is better than treatment. While this is a well-known saying in our society, it holds scientific merit. Most health experts agree that preventing various diseases can reduce treatment costs and lower the likelihood of infection. The same principle applies to preventing HPV infection. However, the recent promotion of HPV prevention has led to the creation of a black market for Gardasil injections. Initially, promotion for the vaccine began through Twitter accounts, with active users and high-follower accounts sharing their experiences of purchasing and receiving the vaccine. On the other hand, many medical bloggers on Instagram, pharmaceutical bloggers, and even hygiene product sellers in pharmacies have created content claiming that HPV infection rates are high and urging the public to purchase Gardasil. They emphasize that anyone who notices genital warts—one of the symptoms of low-risk HPV—should visit a doctor for treatment and vaccination. However, the vaccine is primarily for prevention, not for treating warts or the virus itself.

Interestingly, almost all active individuals in the online space promoting the HPV vaccine are endorsing the foreign Gardasil, even though the domestic HPV vaccine is available in pharmacies. Gardasil, however, is distributed in limited quantities through the legal drug distribution channels in Iran. The 4-valent version has been available through pharmacies, but there has been no legal distribution of the 9-valent vaccine. For the past three months, even the 4-valent vaccine has been unavailable in pharmacies. Previously, each pharmacy’s monthly allocation was around 4 to 5 doses.

According to a detailed report by Farhikhtegan, the distribution of Gardasil has even extended to platforms like Divar (a local classifieds website), where individuals can buy the vaccine. Telegram channels and Instagram pages are also selling Gardasil. Additionally, renowned gynecologists in Tehran are reportedly scaring young women within the eligible age range for Gardasil into believing they have HPV, then selling them the vaccine at exorbitant prices in their clinics. It is said that three out of every six patients visiting these clinics are sold the vaccine.

The price of a dose of the 9-valent Gardasil vaccine on the black market ranges from 10 million to 21 million tomans. So, the total cost for all three doses can range from 30 million to 60 million tomans. The 4-valent Gardasil vaccine is being sold for 8 to 10 million tomans on the black market, whereas its legal price in pharmacies is only about 5 million tomans.

A crucial question here is: if the 9-valent Gardasil vaccine is not legally available, how does it end up in the hands of buyers? It turns out that one can easily purchase it through international travel or from travelers. Vendors selling Gardasil through Instagram easily explain that the vaccine is for "travel purposes" and does not require a doctor’s prescription, meaning it can be purchased in countries like the UAE or Turkey without a prescription.

The unfortunate reality is that with the artificial demand created for Gardasil, it has transformed into a luxury product, and families who can afford it are even giving it as birthday gifts. The combination of propaganda and political economics surrounding the Gardasil vaccine has created a black market for it, even leading to the illegal sale of counterfeit vaccines. Despite the extensive black market, regulatory bodies have yet to take serious action against it, raising questions about which groups are profiting from circumventing legal channels.