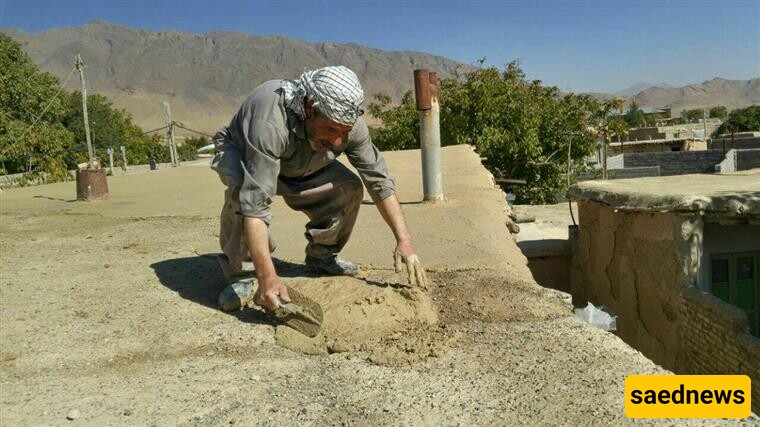

SAEDNEWS: Bon Duey is a ceremony held for plastering the rooftops of houses in the city of Mahan, located in Kerman Province. To learn more about this ceremony, stay with Saad News.

According to SAEDNEWS, The Bon Duey tradition was carried out in the old Mahan. This beautiful practice, which was done through the efforts and cooperation of the people in this city, involved plastering the rooftops of houses, a task known locally as "Bon Duey." People would begin preparations for plastering their roofs at the beginning of Mehr (the first month of the Persian calendar). It usually started with a conversation stemming from the man's concern, as he would say to his wife: "In the spring, when the rain came, I looked at the roof and saw that the mud had blocked the gutters, and the rainwater had washed away the plaster. I need to do something about it, but my hands are tied." The wife would respond: "Don't worry, dear, don't be anxious; God is great. You can bring earth from the clay pit with our two sons or the neighbors starting from the end of summer, and we'll begin. I also have a sack of wheat and a goat kid that I've saved for winter stew. We'll use half of it to prepare lunch for the master and his workers." She would also use a local Kerman proverb: "Bon Duey (plaster) is like a dead body, it doesn't stay on the ground."

Bon Duey

Bon Duey, a tradition of mud-plastering the rooftops of adobe houses, was usually performed once every five years. However, homeowners regularly checked the gutters during the rainy season to prevent them from clogging, ensuring that rainwater didn’t wash away the plaster. Sometimes, roofs didn’t require plastering for as long as eight years.

The process began when the homeowner, with the help of family members, relatives, neighbors, and animals like donkeys and mules, would bring clay from flood areas, rivers, or clay pits near the house. The clay was poured near the house’s walls, close to the roof. The workers then carefully sifted the clay to remove stones, dry wood, or thorns, preventing injury during the process.

Next, they would gather straw, either purchasing it from farmers or collecting it from leftover straw in the wheat fields, known locally as “Sefal.” For each roof section, about 10 to 12 “man” of straw would be needed. In those days, roofs were square-shaped, referred to as "Chahar Pergal" in Kerman dialect, and it wasn’t possible to make rooms any larger. Straw collected from the wheat fields was separated by a tool called "Gorjin," which was used to separate the wheat from the stalks. Soft straw was used for animal feed, while the rougher straw was used for plastering roofs and walls, similar to modern combine harvesting.

Method of Plastering the Roof

After bringing the straw to the worksite, it was mixed thoroughly with the clay. The mixture was then shaped into small mounds, with a well in the center where water was poured. The mixture was left to soak for two days until fully soaked. Once the mixture was ready, it was carried to the rooftop, a task that couldn’t be done alone and required teamwork. This is when neighbors and friends came together in a cooperative and joyful effort.

A scaffold or wooden frame was built, and while some people mixed the clay and straw, others would lift the mixture onto the frame. The mixture, equivalent to a wheelbarrow load, was carried by workers using a wooden door that was secured with ropes. Two workers would pour the mixture onto the roof, while others on the scaffolding spread it evenly. The mixture was carefully placed on the roof to direct the water to the gutters, preventing pooling on the roof.

During the process, a worker stood at the center of the roof to place the plaster mixture into a wooden basket known as a “Zenbil,” which was crafted with precise weaving techniques from pomegranate twigs and sturdy wood from a tree called “Shang.” The basket measured about 60 cm in width and 2.4 meters in length, requiring two workers to carry it. Once filled, it was turned upside down on the roof.

The workers worked in a lively atmosphere, singing, joking, and sometimes getting playfully smeared with plaster, creating a festive atmosphere similar to a wedding or a social gathering. The work was done with humor and camaraderie, and meals like bread and stew were shared among the workers, with the type of food depending on the homeowner’s budget.

Review of the Work

The most important person in the process was the plaster master. He would inspect the mixture of clay and straw each morning to ensure the right balance—too much straw would cause cracks in the plaster, allowing water to seep in, while too little straw would result in the rain washing away the plaster. The master also checked the gutters and roof edges for any issues. During the plastering, an assistant would search the mixture for foreign objects like dry wood, thorns, or stones.

The thickness of the plaster was crucial—about two to four fingers thick—and had to slope towards the gutters so water would flow off the roof rather than collecting. The work typically concluded by midday, and the homeowner would thank the workers with a meal of warm bread and stew, using wheat saved from harvest time and meat from a lamb raised for the winter.

Appreciating the Master

After the work was completed, the master was honored with a hearty meal. The best part of the lamb was reserved for him, and he would often share it with others sitting at the table. The tradition of communal work continued after the meal, with everyone going back to their homes and eagerly awaiting the next opportunity to help each other out.

Final Thoughts

For those interested in witnessing this beautiful tradition, visiting Mahan in Kerman province at the end of summer or the early months of autumn is a great opportunity. In addition to seeing the Bon Duey tradition, you can explore the Prince Garden, the Mazar of Shah Nematollah Vali, and other ancient sites. This practice continues in cities with traditional architecture, and as long as adobe houses remain, this tradition will endure.