SAEDNEWS: The Nobel Prize is usually awarded for great scientific efforts and achievements, but some prizes have had the opposite effect. A few were given for discoveries that later turned out to be completely wrong, and one was even awarded for a brutal medical surgery that left thousands disabled.

According to the Science Service of SaedNews, the Nobel Prizes are among the most prestigious awards in the world. Those who win these awards are usually considered legendary figures in their fields. However, these prizes are awarded by humans, and human judgment is never perfect. Some of the laureates selected by various Nobel committees over the years have been highly controversial or even publicly regarded as wrong choices. Here, on the occasion of the upcoming announcement of the 2025 Nobel Prizes, which begins with the Nobel in Physiology or Medicine on October 5th (14 Mehr), we review some of the worst Nobel Prizes in history.

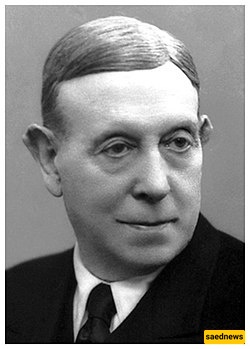

Johannes Fibiger: Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1926

In the past, Nobel Prizes were awarded relatively quickly after a discovery, achievement, or event that prompted it. It seems Alfred Nobel’s guidelines also justified such speed. However, this sometimes led to awards that were later proven baseless. Perhaps the clearest example is the 1926 Nobel Prize in Medicine, awarded to Fibiger for the discovery of Spiroptera carcinoma.

In short, Dr. Fibiger’s research suggested that a type of roundworm called Spiroptera carcinoma could cause cancer in mice. Subsequent experiments, however, showed that the “cancers” he claimed to observe were actually lesions caused by vitamin A deficiency. The worms were not carcinogenic, although some parasites can indeed cause cancer.

This award became even stranger because no prize had been awarded in 1925. Fibiger and Dr. Katsusaburo Yamagawa were on the final list, both for their work on the causes of cancer, but it was decided that none of the papers at the time were worthy enough. Dr. Yamagawa was not included in the 1926 prize, but ultimately, his study proved correct: coal tar is carcinogenic. The Nobel Foundation does not revoke prizes, so Fibiger remains officially listed as the laureate despite his research being disproved.

Fritz Haber: Nobel Prize in Chemistry, 1918

Fritz Haber received his prize for the invention of the Haber-Bosch process, a method for large-scale ammonia production. This process was vital for producing chemical fertilizers and feeding billions of people.

However, Haber is also known for his role in developing chlorine gas as a chemical weapon during World War I and justified the use of chemical warfare throughout his life.

This is a bitter historical irony because Alfred Nobel established the Nobel Prizes precisely out of concern that he would be remembered only for making dynamite and other weapons, after reading a French newspaper that called him a “merchant of death.”

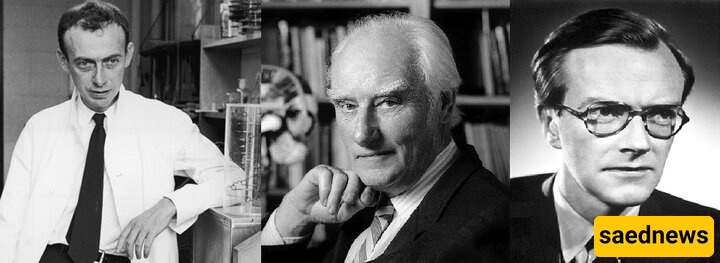

James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins: Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1962

Sometimes the most controversial aspect of a prize is who did not receive it. This was the case for the 1962 prize for the discovery of the “molecular structure of nucleic acids and its significance for information transfer in living matter,” i.e., DNA.

The rule is that only three people can share a Nobel Prize. This rule feels outdated in the era of group research. Nominations after death are also not allowed. So when the DNA prize went to Watson, Crick, and Wilkins, others who contributed to the discovery were excluded.

The most famous person missing from the laureates was Dr. Rosalind Franklin. Her X-ray diffraction work produced images of DNA that were critical for discovering the double helix. The winners initially did not acknowledge her work, and Watson portrayed her contribution negatively in his book. She was never nominated for a Nobel and died in 1958. Many believe she was a victim of gender bias. One of her colleagues, Dr. Aaron Klug, later won the 1982 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for work continuing hers, showing Franklin’s work deserved recognition.

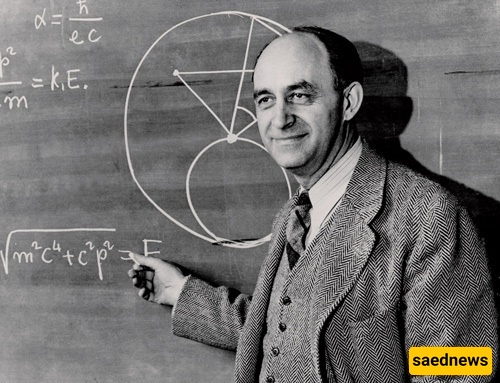

Enrico Fermi: Nobel Prize in Physics, 1938

Sometimes the problem with a scientific discovery is not that it is wrong but that the evidence does not support it. This was the case for the 1938 Physics laureate Enrico Fermi, who received the prize for demonstrating the existence of new radioactive elements produced by neutron irradiation and discovering nuclear reactions caused by slow neutrons.

In 1934, Fermi conducted an experiment that seemed to show unknown elements could be produced by bombarding uranium with neutrons. The elements were named “ausonium” and “hesperium” with atomic numbers 93 and 94.

However, he had not discovered new elements. Instead, he had induced nuclear fission, in which heavy uranium atoms split into lighter elements—something he was unaware of. The elements he thought he created were just mixtures of barium and other known elements. Alternative explanations were proposed the same year, but correct nuclear fission was not recognized until after he received the prize.

Fermi later led the first artificial nuclear reactor and the first controlled chain reaction at the University of Chicago and the Manhattan Project. He also proposed the famous Fermi paradox about extraterrestrial life. The 1944 Nobel Prize in Physics went to Otto Hahn for discovering fission, but Fermi might have also deserved a prize for the same experiments.

Paul Müller: Nobel Prize in Medicine, 1948

Paul Müller did not invent DDT, but he discovered that it was a highly effective insecticide capable of killing large numbers of flies, mosquitoes, and beetles quickly.

This compound was extremely effective in protecting crops and combating insect-borne diseases like typhus and malaria. DDT saved hundreds of thousands of lives and helped eradicate malaria from southern Europe.

However, by the 1960s, environmental activists discovered that DDT harmed wildlife and the environment. The United States banned DDT in 1972, and an international treaty banned it in 2001, with some exceptions for countries fighting malaria.

Antonio Egas Moniz: Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine, 1949

Dr. Moniz, a Portuguese politician who later devoted himself fully to medicine, received the Nobel Prize for discovering the therapeutic value of leucotomy for certain mental illnesses. This was a surgical method to treat psychiatric disorders by severing connections between parts of the brain.

Initially called “prefrontal leucotomy,” American doctors refined it and popularized it as the “lobotomy.” It became widely used, with an estimated 40,000 Americans and 17,000 people in the UK undergoing the surgery. Many surgeries were performed on children or individuals unable to make decisions.

While it reduced anxiety, depression, and psychosis symptoms, prefrontal cutting often stripped patients of personality. Those who underwent it were frequently described as slow, emotionless, unmotivated, aimless, obedient, childlike, and dependent.

By the early 1950s, alternative treatments like medication appeared. The Soviet Union banned the procedure for ethical concerns in the same decade. By the 1970s, most countries made it illegal, though it persisted in France into the 1980s. Concerns existed from the start, and today the procedure is recognized as a brutal relic of the past. Nobel laureate Dr. Torsten Wiesel called Moniz’s prize a “significant error in judgment.”

As mentioned, the Nobel Foundation does not revoke prizes. Its official website includes a section justifying the surgery as the best treatment available at the time.