SAEDNEWS: January 7th Marks the Anniversary of Gholamreza Takhti's Death—An Opportunity for a Different Reflection on the National Hero

According to SAEDNEWS, quoting Tabnak: Takhti did not kill himself. His death serves as a powerful reminder of the loneliness of great individuals, who, at certain points in their lives, may even be cast out from their own homes. It’s enough for them to die for their virtues to be remembered.

On the day the news of Gholamreza Takhti's death spread across cities and villages, seven people in different parts of Iran committed suicide. Among these tragic incidents, the most poignant was the suicide of a butcher in Kermanshah, who hanged himself and left a note on his shop window that read: “The world cannot continue without the National Hero.”

Whether Takhti committed suicide, was murdered, or died naturally, one significant act by the regime shaped his legacy: it prohibited newspapers and media from writing about his death. This silence allowed everyone to talk about Takhti's death in their own way, interpreting it based on their understanding and image of him. In essence, the authoritarian regime unintentionally amplified Takhti’s legendary status.

It all started with a version that claimed, “On January 7, 1968, Gholamreza Takhti committed suicide in Room 23 of the Atlantic Hotel in Tehran due to domestic disputes with his wife.”

The late Jamshid Mashayekhi once said:

"Initially, Takhti married a woman who did not belong to his social class and often mocked him at various gatherings. If he had stayed with her, he wouldn’t have been Takhti; if he had divorced her, he wouldn’t have been Takhti either. The only way for him to remain Takhti was to take his own life."

When Ali Hatami wanted to make a film about Takhti's life, someone told him:

"You can’t make this film because most people won’t accept it." Hatami replied: "Give me 48 hours." He returned with an idea:

"Takhti in a black wrestling singlet fights Takhti in a white singlet. The black Takhti defeats the white Takhti."

Mashayekhi embraced Hatami and said: "That’s perfect."

Mashayekhi added: "I firmly believe he committed suicide."

However, others, including Jalal Al-e Ahmad, accused the SAVAK (Iran’s secret police) of orchestrating his murder due to his immense popularity and lack of loyalty to the regime.

Another account claims that shortly before his supposed suicide, Takhti wrote on a piece of paper borrowed from a hotel servant:

"Suicide is so difficult. You can’t imagine how I feel right now. My whole body is trembling. I can’t believe that tomorrow I’ll be under the ground. Death is so near, and it’s terrifying. But what choice do I have? I must decide. God, end this quickly. I’ve prepared the water. My hands are shaking. My mother is ill. Where is my son? It’s 12:20 a.m."

An hour later, he allegedly wrote again:

"It’s 1:20 a.m. Last night, I couldn’t make a decision. I slept until noon today."

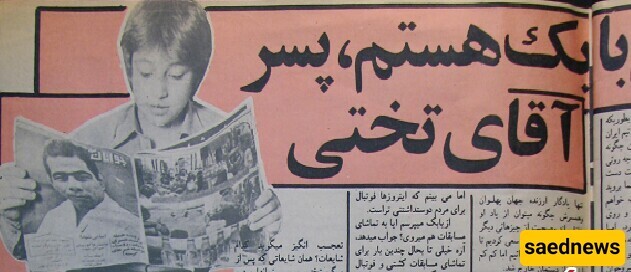

In 1978, Babak, Takhti’s son, said at the age of 11:

"Everyone says something different about my father’s death, and I still don’t know the truth."

Even as an adult, Babak wrote a book about his father, which ends with the same ambiguity he felt as a child.

Takhti's wife also stated in an interview: "We had no disputes. Let them say whatever they want."

Without having lived during Takhti’s time, I’ve often read about him and pondered his circumstances. I’m not concerned with the findings, investigations, or opinions about his death. Just as the regime allowed public imagination to freely craft Takhti’s immortality, I have my own perspective: I believe Takhti committed suicide.

But this wasn’t just any suicide—it feels justified in a way. Constantly diminishing oneself for people you’ve elevated is not humiliating; it’s deeply painful. Beyond a certain point, this pain either kills you or compels you to end it. Staying would have meant fighting those very people, which wouldn’t have suited Takhti. Embracing death seemed more bearable.

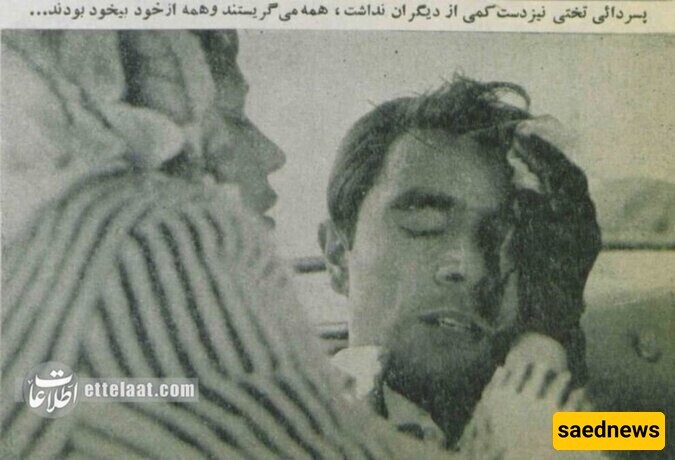

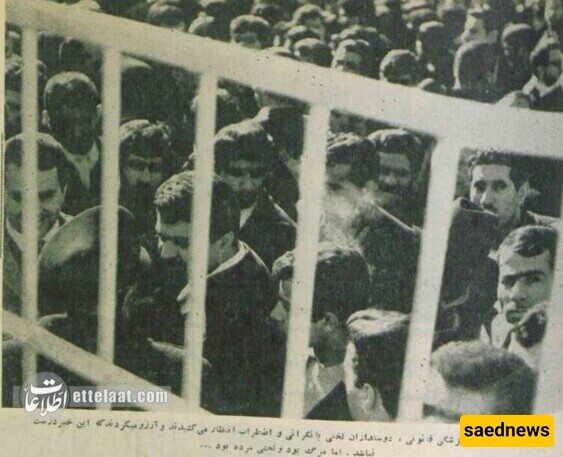

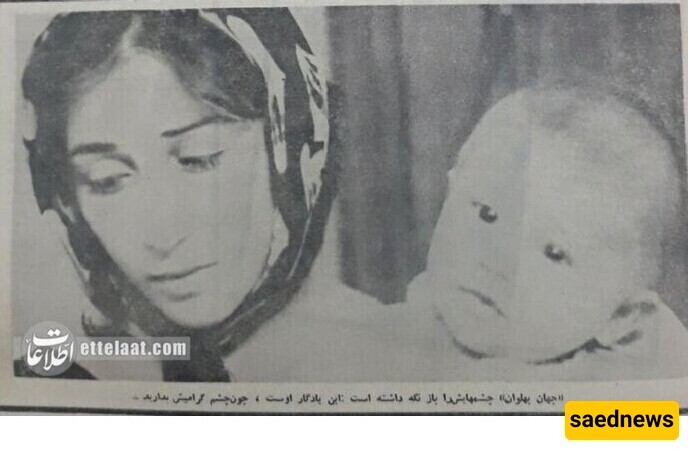

(On the afternoon of January 7, 1968, news of Takhti’s death in Room 23 of the Atlantic Hotel in Tehran shook the city. The following images are from magazines like Ettela’at Weekly, Tehran Mosavar, Kayhan Sports, Sepid o Siah, and Ferdowsi.)

Takhti’s death remains a stark reminder of the loneliness of greatness. Sometimes, it takes death for people to appreciate someone’s virtues.

"Takhti's father-in-law"

"Takhti's cousin" (specifically, the son of his maternal uncle)

"People who have heard the news of the passing of their world champion."

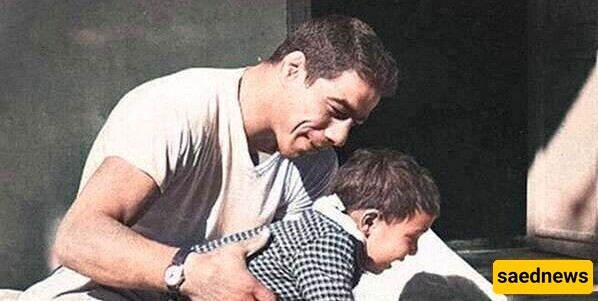

"The wife and son of Takhti."

This narrative parallels that of Rumi, who reportedly endured a lonely death after being cast out of his own home. Decades passed before his greatness was rediscovered. Like Takhti, Rumi may not have realized the magnitude of his legacy during his lifetime.

This reflection isn’t about Takhti’s family but rather the larger community and culture. Loneliness in such a setting often leads to death—if not physically, then spiritually.