SAEDNEWS: 20 Years On, the ‘Mutable Fate Mitaka’ Apartment Remains One of Residential Architecture’s Most Enigmatic Experiences

According to Family Magazine at Saed News, 20 years after its completion, the Mitaka “Mutable Fate” Apartments—built in memory of Helen Keller—remain one of the most enigmatic experiences in residential architecture.

This nine-unit complex, designed on the outskirts of Tokyo by artists and architects Shusaku Arakawa and Madeline Gins, was conceived as a “house for not dying”: a home that constantly engages and provokes its inhabitants, activating both body and mind simultaneously.

The project is built around three primary geometric forms—cube, sphere, and cylinder—irregularly stacked to create complex spatial arrangements. These vibrant structures, affectionately dubbed by writer Setouchi Jakuchou as the “immortal, polychromatic house,” are painted in 14 different colors inside and out, creating a landscape of spatial unpredictability. Together, these elements reflect the architects’ belief in responsive environments that nurture physical and cognitive adaptability from childhood through old age.

The Mitaka apartments represent Arakawa and Gins’s most ambitious attempt to turn their philosophy into form. Since opening in 2005, the spaces have functioned as residences, educational venues, and cultural hubs. Short-term stays in a unit can be booked via Airbnb. To mark their 20th anniversary, a series of public events—including a retrospective exhibition—has been organized.

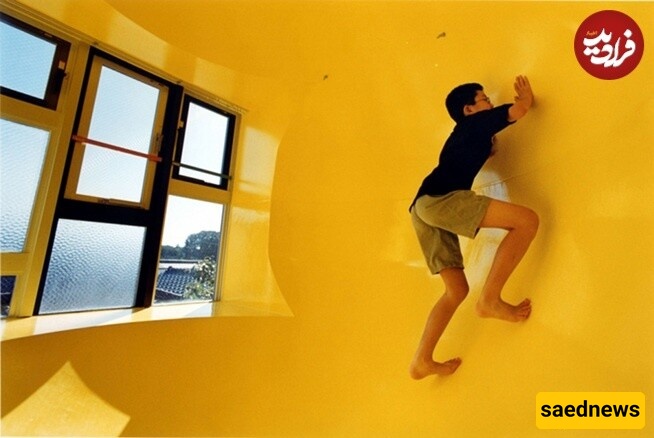

Inside, the apartments are as playful and provocative as their exterior suggests. Uneven flooring encourages instinctive movement, varying ceiling heights and sudden drops, vertical poles, and color-saturated surfaces are all designed to disrupt conventional patterns of perception and motion, keeping body and mind alert. Arakawa and Gins once stated that fate is not fixed but something shaped through spatial experience. Consequently, the Mitaka Mutable Fate Apartments reject standardized architectural neutrality, fostering active, continuous engagement between inhabitants and their environment in unexpected ways.

Though the apartments’ whimsical appearance may recall playgrounds or postmodern fantasies, their theoretical impact runs much deeper. Designed as a “house for not dying,” the project embodies the bold conviction that architecture can challenge mortality itself. Arakawa and Gins developed a philosophy called “procedural architecture,” in which the built environment acts as an active catalyst for cognitive and physical transformation. The aim of this experimental typology is to stimulate the senses, allowing inhabitants to explore the full potential of their bodies while navigating challenging spaces.

The interplay between body, mind, and space becomes central to the design. The experience of climbing, bending, and rebalancing reveals the true purpose of architecture. It considers the needs of all ages, lifestyles, and physical abilities: certain configurations are suited for children, while others accommodate adults. By engaging with physical limits, the apartments’ philosophy acknowledges human differences while remaining dynamic over time.

For Arakawa and Gins, this transformative potential was embodied in the life of Helen Keller, in whose memory the project was created. They saw Keller as a symbol of overcoming adversity—an ideal inhabitant of a home that challenges the very notion of fate.