SAEDNEWS: Scientists, Thanks to AI, Are Close to Finding Luna 9, the Lost First Lunar Lander. Will the 60-Year Mystery of the Soviet Spacecraft’s Whereabouts Finally Be Solved?

According to Saed News Science and Technology Service, thanks to artificial intelligence, scientists are on the brink of locating Luna 9, the first missing lunar lander. Could the 60-year mystery of the Soviet spacecraft’s exact location finally be solved?

After decades, researchers are now close to uncovering the final resting place of Luna 9, the historic spacecraft that became the first human-made object to achieve a soft landing on the Moon.

The first successful human lunar lander disappeared from view long ago. Six decades ago, the Soviet Union launched Luna 9, becoming the first to land a human-made object in a controlled descent on a celestial body. Yet its exact landing site has remained an unsolved mystery.

Advanced orbiters, including NASA’s Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO) and India’s Chandrayaan-2, have mapped the Moon almost inch by inch. These satellites have even recorded the footprints of Apollo astronauts and the paths of Soviet rovers in stunning detail. Yet Luna 9 continues to evade detection. Its small size makes it nearly impossible for even the sharpest orbital cameras to distinguish it among the Moon’s rocks and uneven terrain.

Scientific American reports that recent developments suggest Luna 9’s long disappearance may soon end. A team of space archaeologists from the UK, Japan, and Russia, using advanced machine learning algorithms and open-source data analysis, have identified several potential sites for this space treasure. Researchers hope that detailed imaging from India’s Chandrayaan-2 in the coming months will officially confirm the discovery.

Luna 9 was part of the Soviet Ye-6 program, the second generation of lunar landers, which faced a challenging path to success. Before its ultimate triumph, 11 previous launches failed due to rocket malfunctions, booster failures, or navigation errors. On the twelfth attempt, success was achieved. On February 3, 1966, Luna 9 landed in the Moon’s vast Ocean of Storms (Oceanus Procellarum).

The mission demonstrated that the lunar soil is solid enough to support human and heavier spacecraft landings.

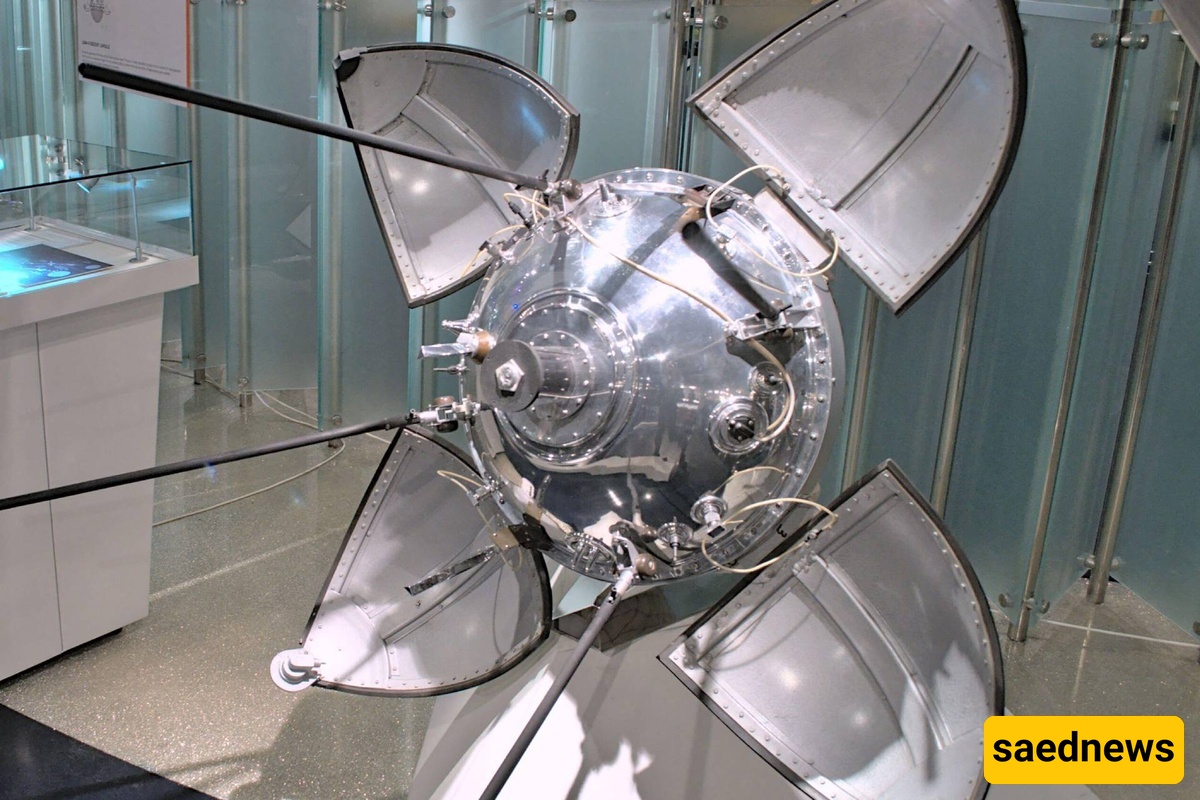

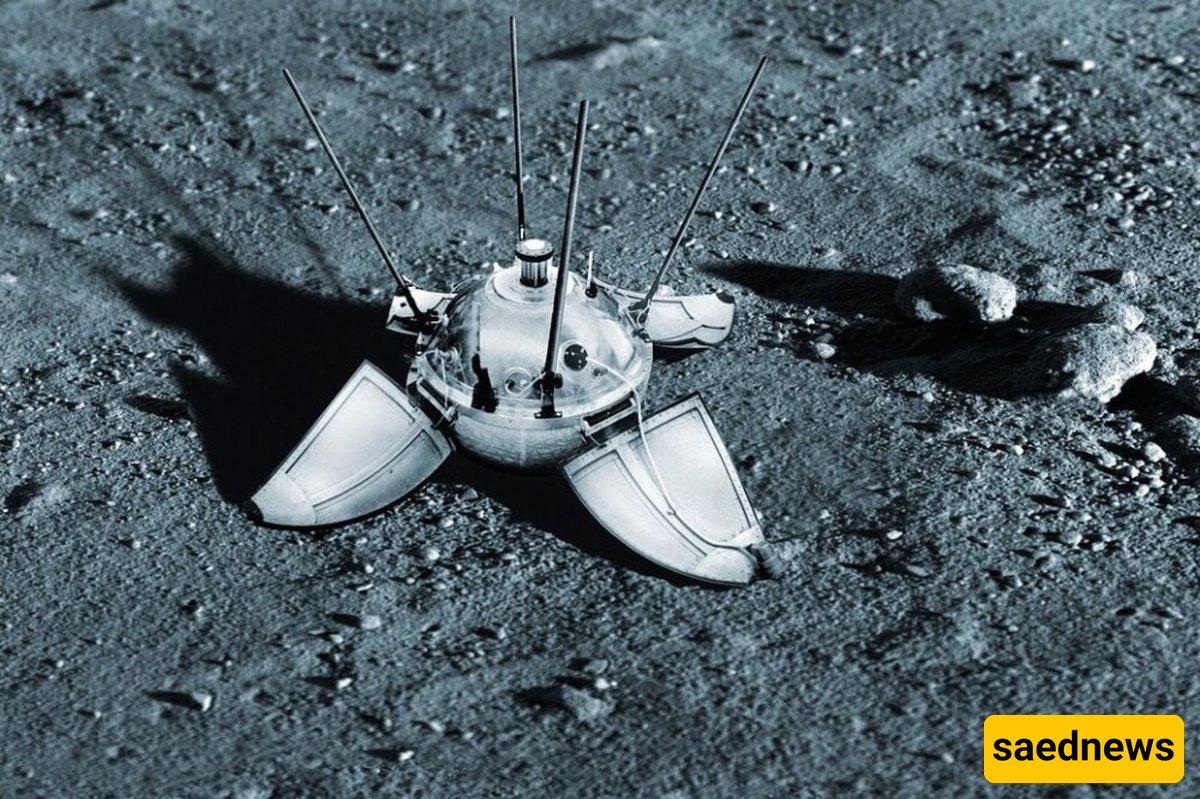

Luna 9’s landing showcased the innovative and unconventional engineering of the Cold War era. Unlike modern landers that descend gently on telescopic legs, Luna 9’s final stage involved dropping a 100-kilogram spherical capsule from five meters, cushioned by air bags. The capsule bounced like a beach ball across the lunar surface, then deployed four petal-like panels to stabilize itself. Of the total 1.5-ton spacecraft launched from Earth, only this small sphere survived to transmit the first lunar surface data.

Its limited batteries lasted only three days, but Luna 9 completed its historic mission in that short time. It sent three panoramic images to Earth and measured environmental radiation, disproving fears that the Moon’s surface was covered with a deep, loose dust layer that could swallow objects.

At the time, the Soviet newspaper Pravda reported the landing site as 7.13° N, 64.37° W, though 1960s computational accuracy was far below today’s standards.

Alexander Basilouski, a leading geochemist involved in selecting future Soviet landing sites, noted that such errors could amount to tens of kilometers. Luna 9’s design allowed it to land safely even on slopes or near boulders, unfolding its petals to begin operations after rolling.

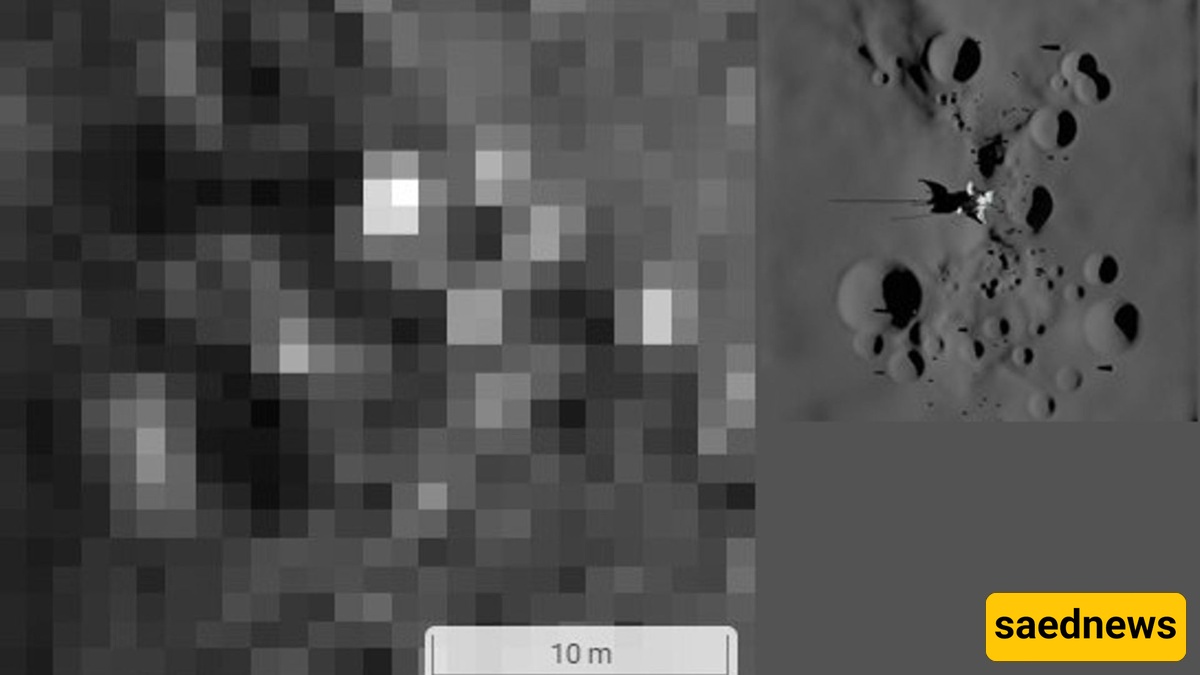

A chance to reevaluate these claims came in 2009 with the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter. Its advanced cameras can detect objects as small as 50 centimeters from 50 kilometers above. Jeff Plescia of Johns Hopkins University spent years examining these images to locate traces of the lander’s descent engine or landing marks, but initially found nothing.

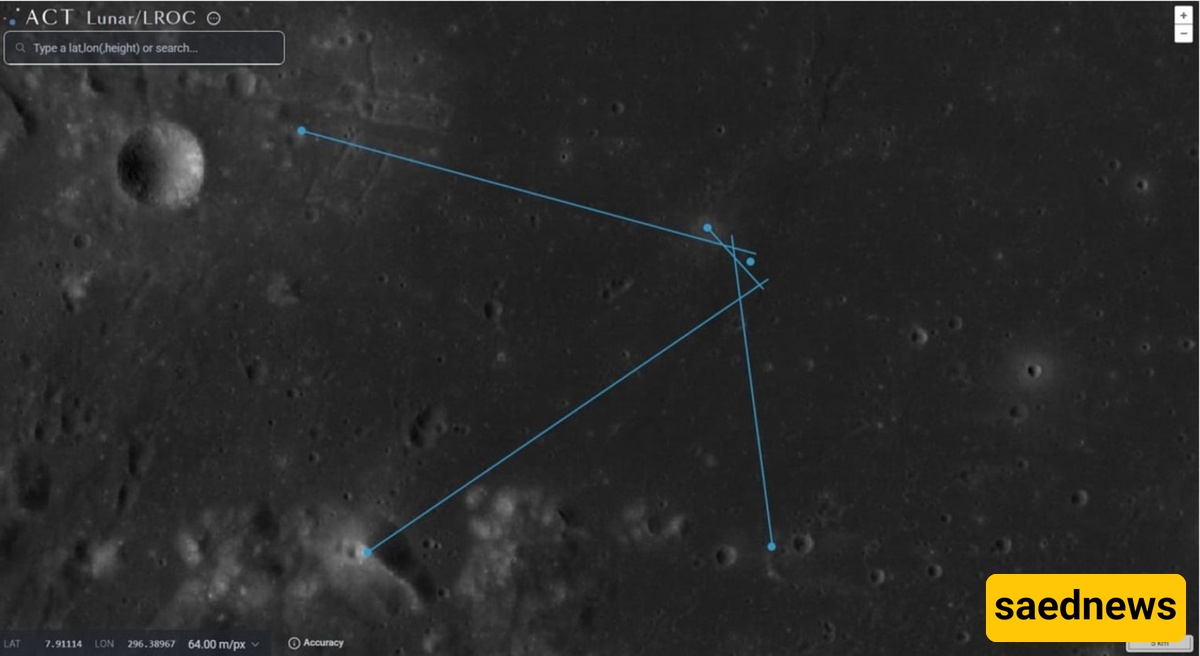

In 2018, researcher and science communicator Vitaly Egorov renewed the search, applying modern triangulation and matching geological features from old Luna 9 images with LRO’s laser topography data. His recalculated coordinates placed the landing site about 25 kilometers from the Soviet-reported location. Egorov shared the data with India’s Chandrayaan-2 team, which plans to capture ultra-high-resolution images (25 cm per pixel) in March 2026, where Luna 9’s main body and petal antennas should be distinguishable.

Simultaneously, a team from University College London and Japanese scientists is employing machine learning to hunt for Luna 9. Their AI system, initially designed to detect small meteoroid impacts, has been trained to recognize human-made objects on the Moon and has identified several suspicious candidates near the reported coordinates, awaiting human verification and new imagery.

In a paper published in npj Space Exploration, researchers emphasized the value of combining AI with human expertise. Locating Luna 9 precisely is not only a historic achievement but also enables scientists to study the effects of cosmic radiation and the Moon’s harsh environment on human-made materials after 60 years.

The scientific community now awaits March and the images from India, hoping to finally reveal the resting place of the lost Soviet Luna 9. As Egorov notes, one day, space tourists may visit this historic site to pay homage to humanity’s first robotic steps on the Moon.