Saed News: Decorated skulls were likely made from the heads of the dead centuries before burial and were revered. / Source: Faradid

Saed News History Service reports, quoting Faradid: About 9,000 years ago, during the Pre-Pottery Neolithic period, ancient inhabitants of the Middle East began the strange practice of plastering the skulls of their dead. These plaster-covered skulls were decorated with colorful pigments and other ornaments to make them look more lifelike, although historians are not exactly sure why or how this peculiar tradition originated.

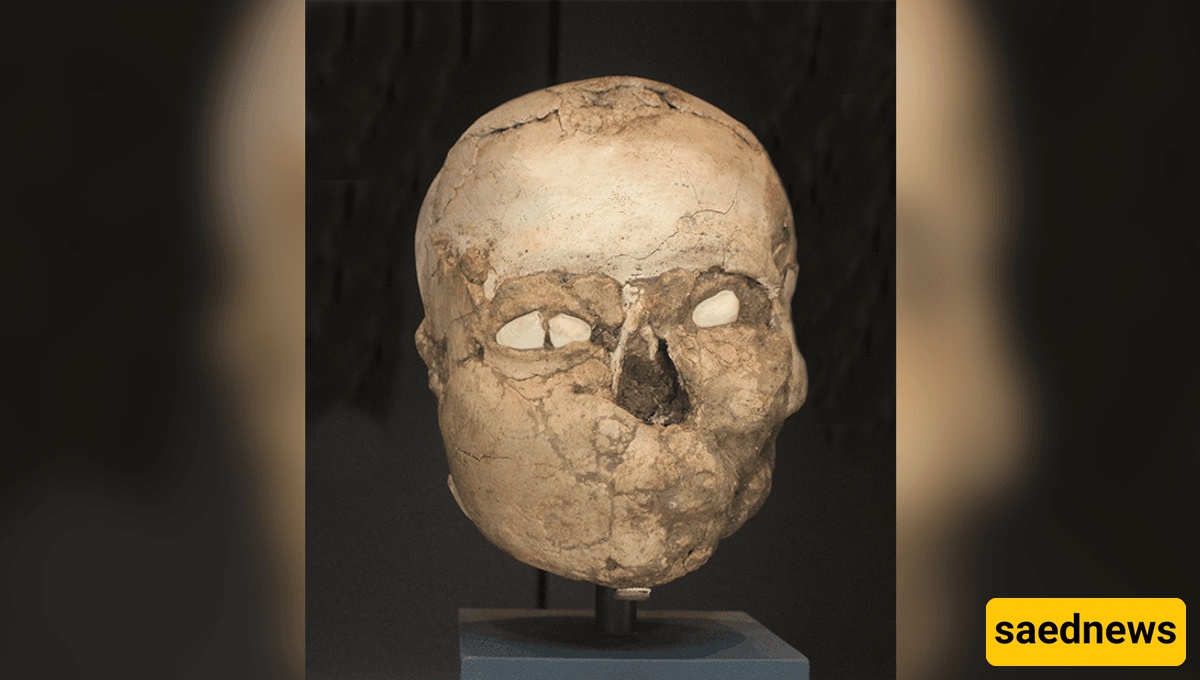

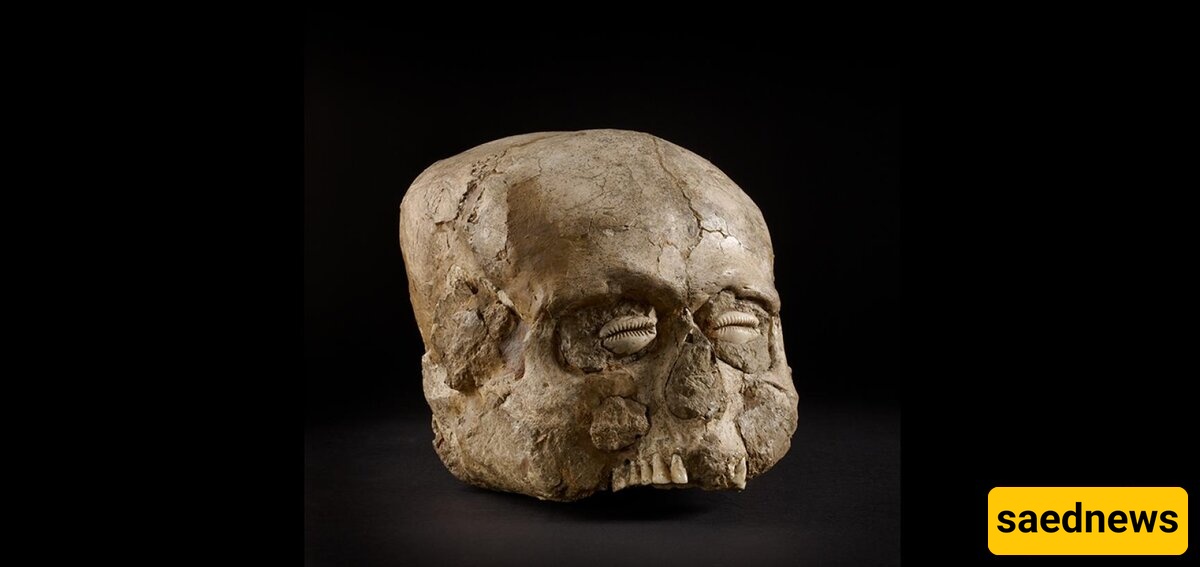

The first plastered Neolithic skulls were discovered in 1953 by archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon in the Palestinian city of Jericho. These remains were covered with colorful plaster masks and had shells placed in the eye sockets, perhaps to reconstruct the eyes of the original owners.

Similar examples from roughly the same period have been found across the Levant and Anatolia, though interpretations of this unusual burial ritual vary. The most popular explanation is that the skulls were covered with plaster masks to give them new life and that these objects were worshipped as ancestral figures.

Researchers aiming to uncover the mysteries surrounding these ancient heads have conducted detailed analyses on seven plastered skulls found at the Tepecik-Çiftlik archaeological site in Turkey. According to the researchers, the skulls belong to six young adults and one child, who were likely specifically chosen for this unique tradition.

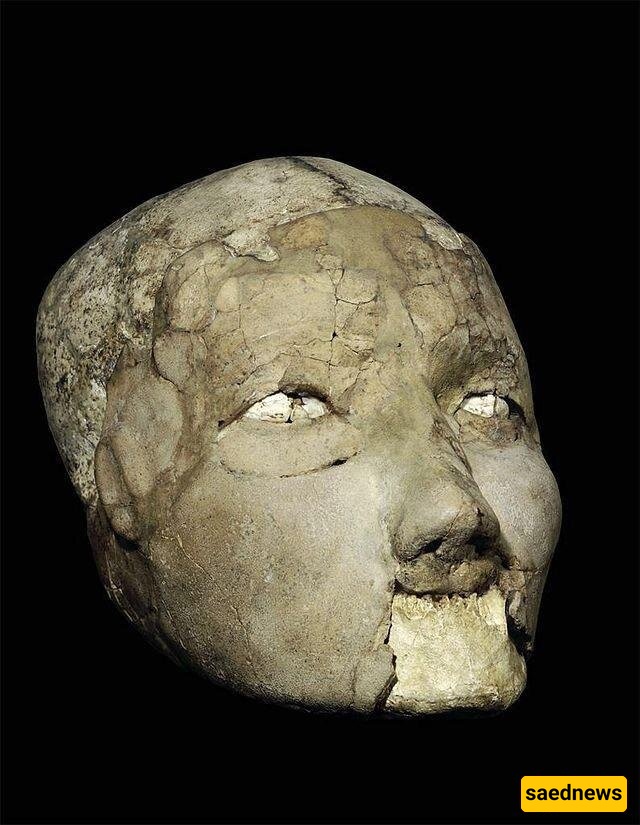

Like other plastered skulls, these remains were coated with a material colored by a range of pigments. The researchers identified pigments including azurite and goethite, indicating red and blue colors on the plaster masks: “Selected pigments were used to create an impressive appearance, although the Tepecik-Çiftlik skulls lack decorations such as shells for the eyes.” The researchers believe these findings align with other examples and point to a widespread “craftsmanship” likely transmitted through an oral culture.

Perhaps most interestingly, the researchers discovered that these plastered skulls are several hundred years older than the graves in which they were buried—meaning they were used for a long time before being interred: “These results may indicate long-term community use of plastered skulls.”

During their long period of use, plastered skulls likely required several rounds of handling and restoration, evidence of which can be seen in some of the Tepecik-Çiftlik skulls.

Other findings, such as cut marks on the bones themselves, provide tangible evidence that the soft tissues of these selected skulls were removed before the plastering process began.

However, despite gaining fascinating insights into the history of these incredible artifacts, researchers still do not know the exact reason for plastering the skulls or how they were used.