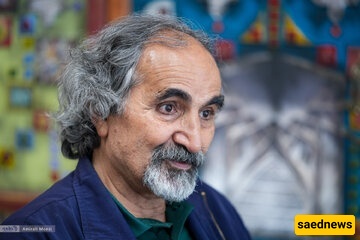

SAEDNEWS: In a sweeping interview with Iran newspaper, sociologist Taqi Āzād Armakī argues that Iranian society’s drive to live as a modern community inevitably tramples bans—first on video, then on satellites, and now on cyberspace—and calls on policymakers to recognise and embrace this transformation.

According to Saed News, in a conversation with Iran newspaper, Taqi Āzād Armakī identified the Iranian public’s foremost demand as “to live in a modern—or “new”—world while retaining its cultural, civilisational, and religious roots.” He explained that, despite persistent resistance from policymakers, society has repeatedly dismantled prohibitions—first against video tapes years ago, then against satellite dishes, and now against the restrictions on virtual spaces and communication networks—simply by adopting and consuming these technologies.

When asked how to categorise today’s most urgent social demand in post‑war Iran, Armakī replied: “The loudest demand, though overlooked until recently, is for modern life in the contemporary world—a world whose features people know and wish to inhabit, without abandoning their heritage.” He noted that on each occasion the authorities attempted to block video recorders, satellite receivers, and now social media, Iranian society simply moved forward, consuming each medium in turn.

Armakī emphasised that, over time, policy‑making resistance yields to reality: “In every instance, the policymaking domain ultimately steps aside and is forced to accommodate change.” He argued that Iranians do not wish to erase their past—Iranian or Islamic culture—but to engage in a dialogue between past and present so as to harness new tools for everyday life.

When pressed on what such a society demands to achieve this modern existence, Armakī identified “tension reduction” as the key. He suggested that once this core issue is addressed, many heated debates will recede, allowing scholars and the middle‑class intelligentsia to redefine Iran’s relationship with the outside world, reconstructing the meaning of domestic cultural products vis‑à‑vis Western ones.

He asserted that resolving some challenges simply gives rise to new questions about Iran’s external relations—questions best handled by academics, experts, and national bourgeois thinkers, rather than by a single ministry. “In societies where unilateralist groups attempt to monopolise agency,” he warned, “they ignore social transformations—and this oversight serves as a warning.”

Armakī proposed that the solution lies with reformist and critical social actors who must both recognise and legitimise change. He cited the rise of public‑opinion polling and social‑research studies over the past 30–40 years as evidence that when policymakers referred to such research on social values, decision‑making became smoother. His prescription: “Entrust social change to social scientists. If our governance seeks to mitigate the hardship of change, it must devolve responsibility to them—allowing them to speak, produce meanings, and quietly integrate findings into policy. Only through this silent exchange, mediated by the intelligentsia and civil society, can reform proceed with minimal cost to all parties.” He concluded that sudden, overt policy shifts are neither feasible nor desirable, given the unpredictability of their consequences.

Armakī reminded readers that resistance to change is universal—even Germany, cradle of radical thought, brims with both innovation and vociferous critics. By normalising opposition, he urged, Iran can continue its transformation without fear each time new voices speak up.