Kolah-Mali refers to the craft of making hats from animal wool. In this article, we will explore this traditional art. Stay with Saeed News.

Kolah-Mali (Traditional Felt Hat Making) is an art that has flourished for many years in Najafabad County. Until just a few years ago, felt makers and hat makers in the city’s marketplace used to produce various types of felt hats, felt coats, and more. These items were mostly used by nomads, the Lur ethnic group, villagers, and residents of nearby towns. The primary raw material for felt-making is usually sheep wool or goat down (kurk). However, due to the high cost of kurk, hats made from this material are expensive and not cost-effective. On average, about 15 to 20 misqals (roughly 70–90 grams) of wool or kurk are used for each hat.

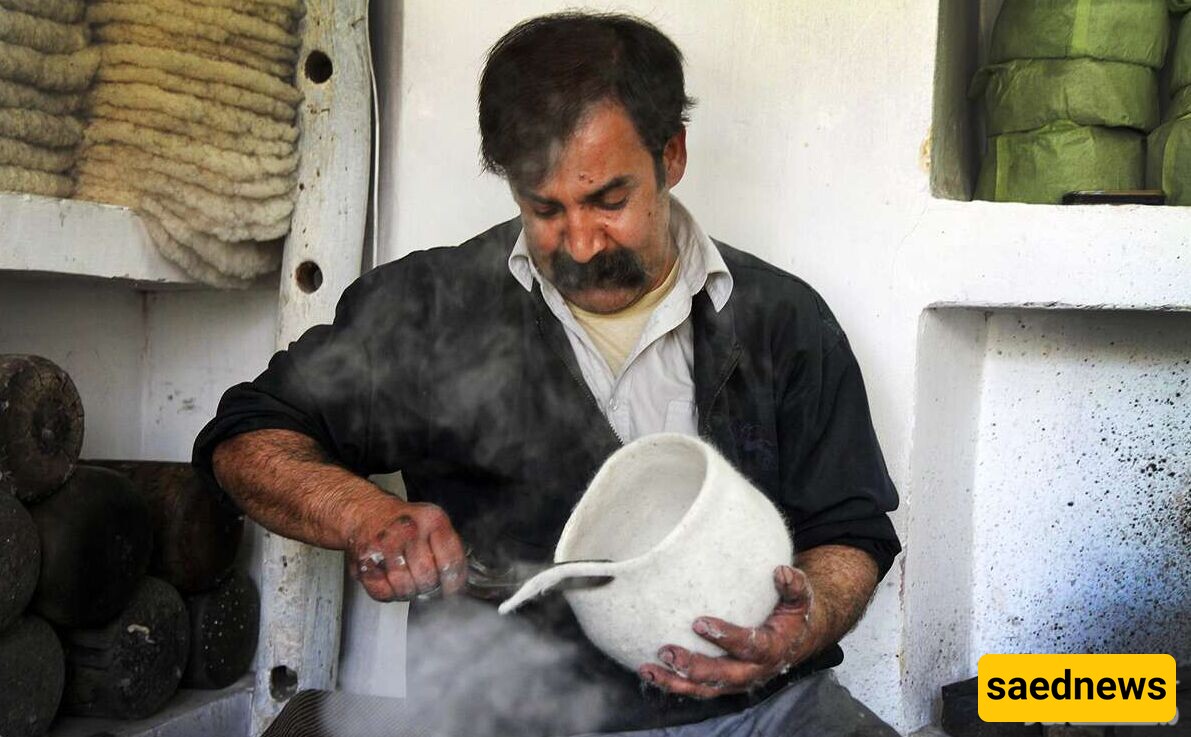

To make a thick hat, about 20 misqals of sheep wool is needed, while thinner hats require around 15 misqals. After the wool is carded, it is kneaded with soapy water. Then the kneaded wool undergoes a process known locally in Najafabad dialect as Engareh, meaning mold shaping. For this, a special furnace must be preheated. After the wool becomes firm (a stage called ham gereftan in local dialect), it is rubbed intensively—similar to the traditional felt-making craft. Once the basic shape of the hat is formed, it is placed in one of five types of molds, depending on the desired size and shape. After molding, the hat moves on to the coloring stage.

After molding, the hat is dyed. In the traditional Kolah-Mali craft, mainly natural dyes are used—such as alum and pomegranate peel. The hat is boiled for 12 hours in a solution known as Joft, made from oak bark and pomegranate skin. Then it is removed from the pot after 8 hours and rinsed in running water. During washing, a limewater solution is prepared. This helps brighten or "open" the color of the hat. The hat is then immersed in this solution, washed again, and finally rubbed by hand with oil lamp soot by the felt maker. During this stage, the hat undergoes a process called Til-Pich, which is like wringing out old clothes by hand. Once dry, a substance called Zado is applied, the hat is reheated and reshaped using a special pan, and its inner edges are tucked in. It is then dried in the sun, and finally, the inner and outer surfaces are polished with special stones called Hajar.

The last step involves removing any leftover plant debris or burnt fibers. This is done by spinning the hat over a portable gas burner (called Piknik) and gently scraping off imperfections using a rough cloth or loofah. Once completed, the hat is ready to be sold. In the past, most hats made in Najafabad were bought in bulk by merchants from Mamasani, Tuyserkan, and Hamedan. They were made from local sheep wool, which had higher quality and durability. Over time, due to the roughness of local wool and cultural changes, synthetic fibers—often referred to as “Australian sheep wool”—became more commonly used.

It’s worth noting that the average lifespan of these traditional hats is about 3 years. With low startup costs and a relatively good market—especially if production is diversified—this craft can be a viable employment option for the younger generation in the region. However, Kolah-Mali no longer enjoys the same popularity as in the past, and most of its current customers are villagers and people from nearby towns.