Saed News: Researchers have shown that when ants work together to solve problems, they perform better than humans.

According to the Science and Technology section of Saed News, citing Zoomit, the findings of a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences provide new insights into group decision-making and explore the advantages and disadvantages of collaboration versus working individually.

According to Zoomit, researchers used a well-known problem called the "Piano Moving Puzzle" to compare the teamwork abilities of humans and ants. This puzzle is a mathematical challenge involving the movement of a large, heavy object (such as a piano) in a crowded or complex environment.

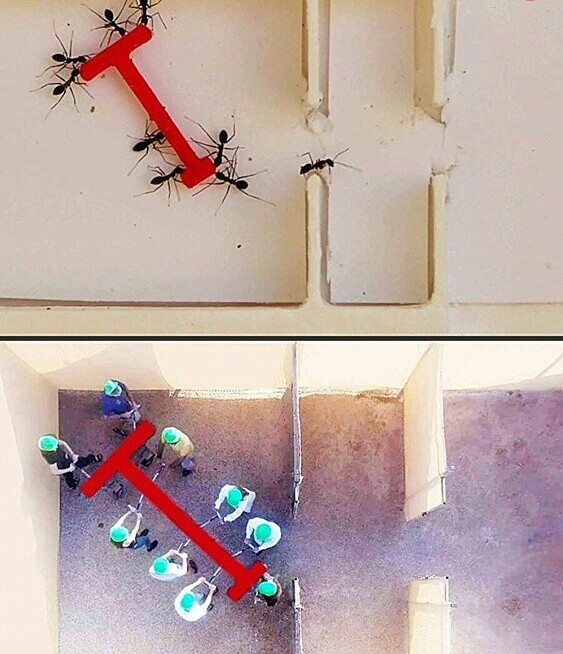

In the new study, participants were given a large T-shaped object instead of a piano, which had to be moved within a rectangular space divided into three sections connected by two narrow gaps. Participants were tasked with moving the object between sections without hitting walls or obstacles.

Two types of mazes were created: one scaled for ants and another for humans. Additionally, different maze sizes were used to test various group configurations.

Recruiting human participants was straightforward, as they were motivated either by the request or the appeal of the challenge. In contrast, ants participated unintentionally, thinking the heavy object they were moving was a piece of food to be taken to their colony.

The ants selected for this experiment belonged to the species Paratrechina longicornis, commonly known as "crazy ants" due to their erratic and seemingly aimless movements. These ants, measuring about 3 millimeters, are found worldwide.

The ants performed the maze task under three conditions: a single ant, a small group of seven ants, and a large group of 80 ants. Similarly, humans participated as individuals, in small groups of 6–9 people, and in larger groups of 26 people.

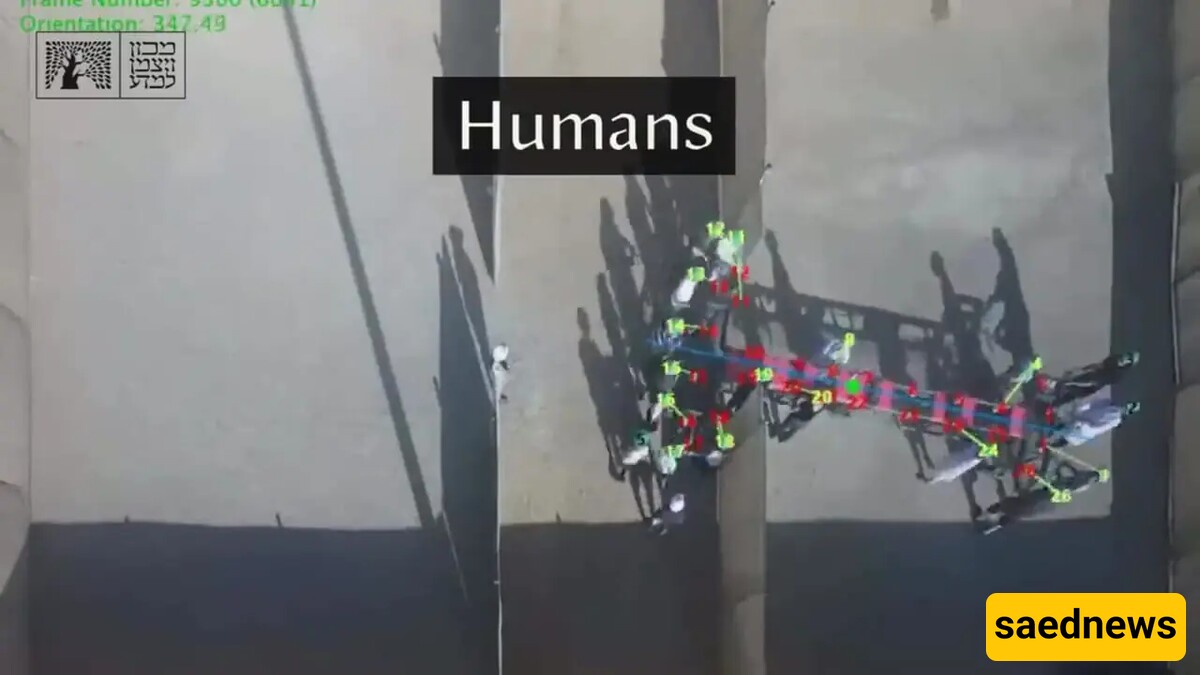

To ensure fairness, humans were sometimes restricted from speaking or using gestures, even being given masks and sunglasses to limit nonverbal communication. They were required to use special handles to move the object, designed to mimic how ants carry objects. These handles also measured the force applied by each participant.

The experiments were repeated multiple times for each condition, with researchers carefully analyzing videos, collected data, and using computational models and physical simulations.

Predictably, humans outperformed ants in individual tasks due to their superior intelligence, leveraging thoughtful planning to achieve better results.

However, group challenges yielded contrasting results. Larger ant groups significantly outperformed individual ants, and in some cases, even surpassed human groups. The ant groups exhibited coordinated movement, collective memory, and avoidance of repeated mistakes.

In contrast, human group performance did not improve much, and when communication was restricted to emulate ant behavior, their results were worse than when working individually. Humans often opted for seemingly efficient short-term strategies that were less effective in the long run.

Researcher Ofer Feinerman explained that an ant colony operates like a family, with all ants sharing mutual interests and working cooperatively rather than competitively. This unity allows the colony to function as a "superorganism," where individual ants collaborate as parts of a cohesive whole.

Feinerman noted, "We showed that ants act more intelligently when they work in groups. However, forming groups did not enhance humans' cognitive abilities. The collective intelligence often discussed in the era of social networks was not observed in our experiments."