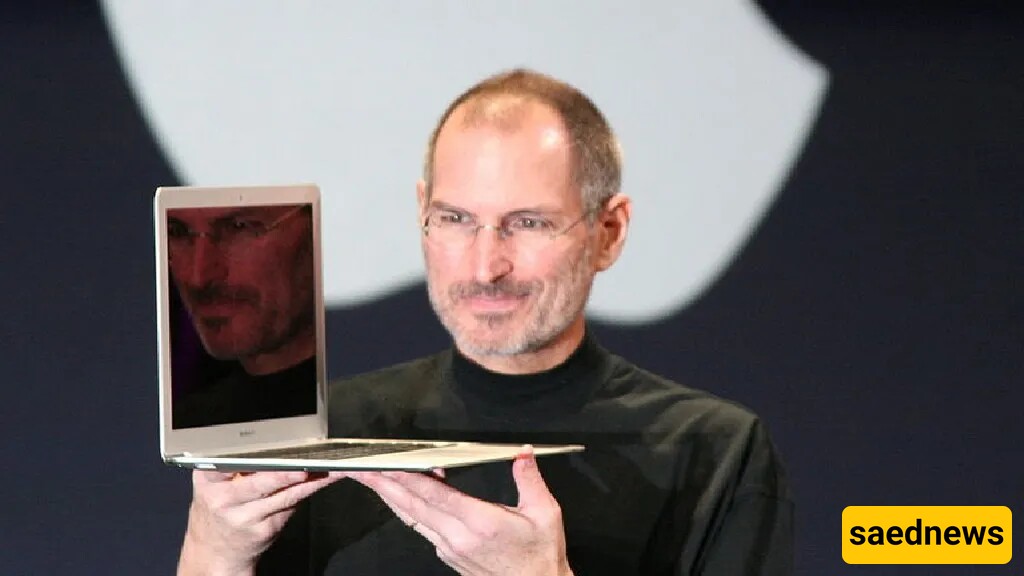

SAEDNEWS: The first 2 of many imperatives that drive Jobs' approach: Focus and simplify.

According to SAEDNEWS, his narrative is the business creation myth writ large. Steve Jobs cofounded Apple in his parents' garage in 1976, was fired in 1985, returned to save the firm from near bankruptcy in 1997, and by the time he died in October 2011, had transformed it into the world's most valuable company. Along the way, he contributed to the transformation of seven industries: personal computer, animated movies, music, phones, tablet computing, retail outlets and digital publishing. As a result, he ranks among Thomas Edison, Henry Ford, and Walt Disney as one of America's greatest inventors. None of these individuals were saints, but long after their names are forgotten, history will remember how they used imagination in technology and business.

When Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, the company was producing a diverse range of computers and accessories, including a dozen distinct Macintosh models. After a few weeks of product reviews, he'd had enough. "Stop!" he exclaimed. "This is crazy." He took a Magic Marker, padded his bare feet to a whiteboard, and created a two-by-two grid. "Here's what we need," he said. He labeled the two columns "Consumer" and "Pro." He designated the two rows as "desktop" and "portable." He advised his staff that they needed to focus on four exceptional goods, one for each quadrant. All remaining items should be canceled. There was startled quiet. But by pushing Apple to focus on creating only four computers. "Deciding what not to do is as important as deciding what to do," he shared with me. "That's true for companies, and it's true for products."

After turning the firm around, Jobs began hosting annual retreats for his "top 100" employees. On the final day, he would stand in front of a whiteboard (he like whiteboards because they allowed him entire control over a situation and encouraged attention) and ask, "What are the ten things we should be doing next?" People would battle to get their recommendations included on the list. Jobs would jot them down—and then cross out the ones he deemed foolish. After considerable jockeying, the group would come up with a list of ten. Then Jobs would slash the bottom seven and announce, “We can only do three.” Focus was ingrained in Jobs’s personality and had been honed by his Zen training. He relentlessly filtered out what he considered distractions. Colleagues and family members would at times be exasperated as they tried to get him to deal with issues—a legal problem, a medical diagnosis—they considered important. But he would give a cold stare and refuse to shift his laserlike focus until he was ready.

Near the end of his life, Jobs was visited at home by Larry Page, who was about to resume control of Google, the company he had cofounded. Even though their companies were feuding, Jobs was willing to give some advice. “The main thing I stressed was focus,” he recalled. Figure out what Google wants to be when it grows up, he told Page. “It’s now all over the map. What are the five products you want to focus on? Get rid of the rest, because they’re dragging you down. They’re turning you into Microsoft. They’re causing you to turn out products that are adequate but not great.” Page followed the advice. In January 2012 he told employees to focus on just a few priorities, such as Android and Google+, and to make them “beautiful,” the way Jobs would have done.

Jobs' Zen-like capacity to focus was matched by a corresponding impulse to simplify things by focusing on their core and removing extraneous components. "Simplicity is the ultimate sophistication," Apple's initial marketing brochure stated. against appreciate what it means, compare any Apple program against Microsoft Word, which is becoming increasingly ugly and packed with nonintuitive navigational ribbons and obtrusive features. It serves as a reminder of Apple's success in simplifying its products. Jobs learned to value simplicity while working the night shift at Atari as a college dropout. Atari's games have no manuals and were designed to be simple enough for a stoned freshman to figure out. The only instructions for its Star Trek game were: “1. Insert quarter. 2. Avoid Klingons.” His love of simplicity in design was refined at design conferences he attended at the Aspen Institute in the late 1970s on a campus built in the Bauhaus style, which emphasized clean lines and functional design devoid of frills or distractions.

When Jobs visited Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center and saw the plans for a computer that had a graphical user interface and a mouse, he set about making the design both more intuitive (his team enabled the user to drag and drop documents and folders on a virtual desktop) and simpler. For example, the Xerox mouse had three buttons and cost $300; Jobs went to a local industrial design firm and told one of its founders, Dean Hovey, that he wanted a simple, single-button model that cost $15. Hovey complied.

Jobs sought simplicity by mastering complexity rather than just disregarding it. Achieving this level of simplicity, he thought, would result in a system that seemed to defer to users rather than challenge them. "It takes a lot of hard work," he told me, "to make something simple, to truly understand the underlying challenges and come up with elegant solutions." In Jony Ive, Apple's industrial designer, Jobs found his soul match in the pursuit of profound rather than superficial simplicity. They understood that simplicity is more than just a minimalist aesthetic or the elimination of clutter. To eliminate screws, buttons, or extra navigational displays, each element's job has to be well understood.. “To be truly simple, you have to go really deep,” Ive explained. “For example, to have no screws on something, you can end up having a product that is so convoluted and so complex. The better way is to go deeper with the simplicity, to understand everything about it and how it’s manufactured.”

During the design of the iPod interface, Jobs tried at every meeting to find ways to cut clutter. He insisted on being able to get to whatever he wanted in three clicks. One navigation screen, for example, asked users whether they wanted to search by song, album, or artist. “Why do we need that screen?” Jobs demanded. The designers realized they didn’t. “There would be times when we’d rack our brains on a user interface problem, and he would go, ‘Did you think of this?’” says Tony Fadell, who led the iPod team. “And then we’d all go, ‘Holy shit.’ He’d redefine the problem or approach, and our little problem would go away.” At one point Jobs made the simplest of all suggestions: Let’s get rid of the on/off button. At first the team members were taken aback, but then they realized the button was unnecessary. The device would gradually power down if it wasn’t being used and would spring to life when reengaged.

In looking for industries or categories ripe for disruption, Jobs always asked who was making products more complicated than they should be. In 2001 portable music players and ways to acquire songs online fit that description, leading to the iPod and the iTunes Store. Mobile phones were next. Jobs would grab a phone at a meeting and rant (correctly) that nobody could possibly figure out how to navigate half the features, including the address book. At the end of his career he was setting his sights on the television industry, which had made it almost impossible for people to click on a simple device to watch what they wanted when they wanted.

Steve Jobs' legacy at Apple is defined by his unrelenting concentration and desire for simplicity. He converted Apple from a failing firm to a worldwide superpower by limiting Apple's product portfolio to only a few high-quality gadgets and instilling a culture of focus in his workforce. Jobs knew that emphasis required saying "no" to excellent ideas in order to say "yes" to great ones, and he applied this principle to all aspects of Apple's products and strategy. His love for simplicity extended beyond minimalism to the creation of genuinely intuitive and elegantly designed goods, with the goal of making technology feel natural and accessible. Jobs' imaginative approach taught the tech sector that simplicity and focus are more than simply design. In upcoming parts, we’ll explore more of Jobs’s powerful mantras that drove his groundbreaking success.