SAEDNEWS: Stretching over 237,000 km² between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula, the Persian Gulf—home to 730 billion barrels of proven oil reserves and some of the world’s richest marine biodiversity—remains both a strategic maritime lifeline and a flashpoint of regional identity.

The Persian Gulf is the world’s third‑largest gulf, with a history spanning thousands of years. Politically, economically, and geographically, it ranks among the most significant waterways on the planet.

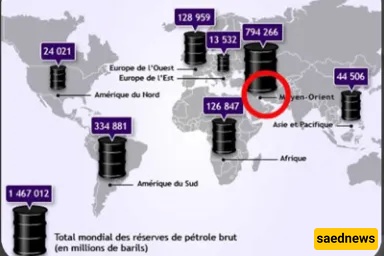

The Persian Gulf’s strategic location and vast energy reserves make it one of the world’s most vital maritime routes. Consequently, it has faced numerous challenges throughout history. According to the latest estimates, the Persian Gulf region holds approximately 730 billion barrels of proven oil reserves and over 70 trillion cubic meters of natural gas.

In addition to oil and gas, the Persian Gulf is one of the richest marine environments on Earth. Pearls, phosphates, sulfur, coral, and a variety of fish and shrimp species add to its wealth. The gulf’s warm waters and islands are home to colorful shells that harbor beautiful pearls—many of which are exported around the globe each year.

These attributes have made the Persian Gulf one of the world’s most important—and most contested—regions, with its name and resources the subject of ongoing debate among regional and global powers.

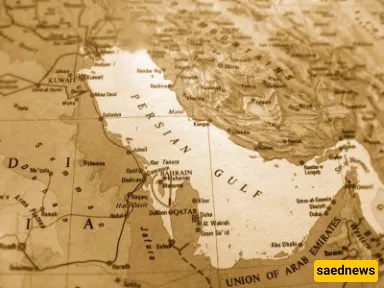

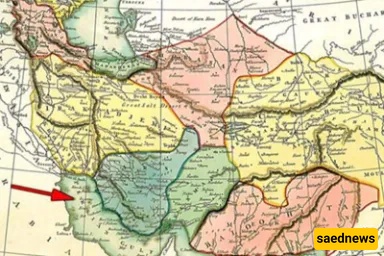

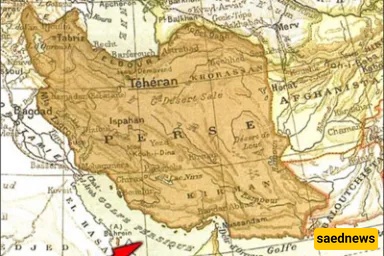

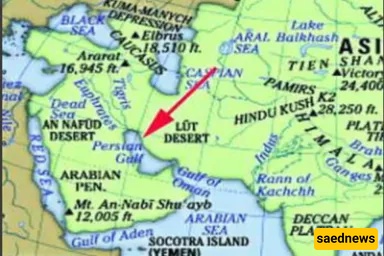

The Persian Gulf (also known in classical sources as the Parsian Channel) is the inlet of the Gulf of Oman, situated between Iran and the Arabian Peninsula. Covering an area of 237,473 km², it is the world’s third‑largest gulf after the Gulf of Mexico and Hudson Bay.

Geologists believe that about 500,000 years ago the first form of the Persian Gulf formed adjacent to Iran’s southern plains. Over time, tectonic and sea‑level changes sculpted its current shape. Initially, the gulf was far more expansive—until the late Tertiary period, much of the Bostan, Behbahan, and Khuzestan plains, as well as areas up to the Zagros Mountains, lay submerged.

Located between 24° and 30°30′ N latitude and 48° to 56°25′ E longitude, the gulf connects to the Gulf of Oman via the Strait of Hormuz, and from there to the world’s oceans. Among its littoral states, Iran shares the longest coastline—approximately 1,800 km including islands (1,400 km excluding them). The gulf stretches about 805 km westward from the Strait of Hormuz, spans up to 290 km at its widest, and reaches a maximum depth of 93 m some 15 km off Greater Tunb. Its shallowest areas, at 10–30 m deep, lie toward its western end.

The Persian Gulf experiences a hot, semi‑tropical desert climate. Summer temperatures can soar to 50 °C, and evaporation often exceeds freshwater inflow. Winters may see lows around 3 °C. Despite the gulf’s high salinity, some 200 brackish submarine springs and 25 completely fresh springs along its shores—fed by the Zagros Mountains—provide vital freshwater sources.

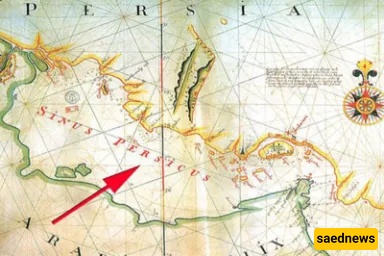

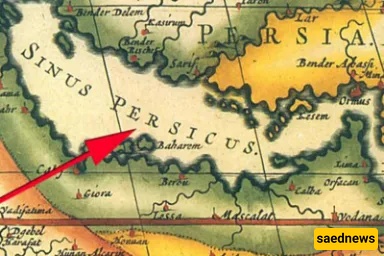

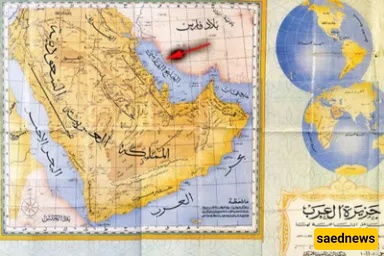

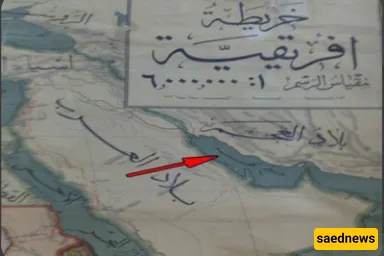

Historically, in all major languages the gulf has been referred to as the “Persian Gulf” or “Sea of Persia,” and every international organization uses the Persian Gulf as its official name. Nevertheless, some Arab states refer to it by the contrived title “Arabian Gulf” or simply “The Gulf.” The International Hydrographic Organization, for instance, uses “Gulf of Iran.”

Interestingly, a body of water called the “Arabian Gulf” does exist—known to the Romans as Sinus Arabicus, but in earlier sources applied to the Red Sea, between the Bab al‑Mandab and Suez Canal. Greeks called that sea Erythra Thalassa (“Red Sea”), and Romans Mare Rubrum. Meanwhile, Greeks consistently named our subject the Persian Gulf, reserving “Arabian Gulf” for the Red Sea. The historian Herodotus frequently referred to the Red Sea as the Arabian Gulf.

Most research traces attempts to appropriate the gulf’s name to the 1920s (the 1340s AH), although whether the British or local Arabs initiated it remains contested. After Britain’s 1837 attack on Kharg Island, Iran formally protested the separatist British policies in the gulf, prompting The Times of London in 1840 to bizarrely call it the “British Sea”—a label that never caught on elsewhere.

Some scholars link the renewed push in the 1960s to Pan‑Arabism. Others point to Roderic Owen, a British political agent, who in his writings used the term “Arabian Gulf,” which then spread among other states. From 1962, efforts intensified in parts of the Arab world. Sir Charles Belgrave, Britain’s political agent in Bahrain, is often—but mistakenly—cited as the originator in 1966; in fact, Belgrave had simply noted that “some Arabs today call it the Arabian Gulf,” while the real campaign began in the 1920s under his watch.

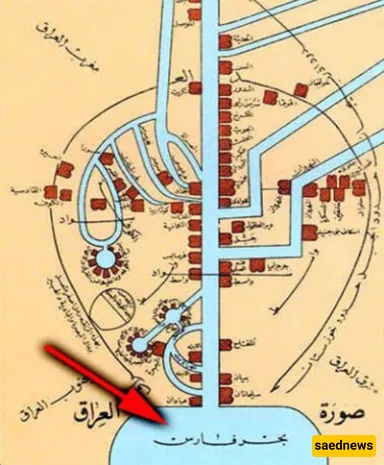

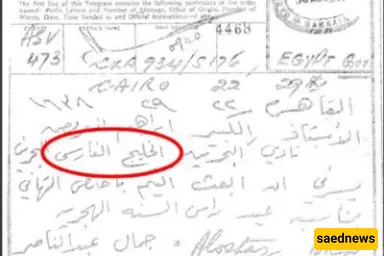

In 1958, during Iraq’s coup, Colonel Abd al‑Karim Qasim sought to galvanize Arab support by renaming the gulf and Khuzestan, hoping to redirect regional focus from Cairo to Baghdad. This scheme failed, and Kuwait, fearing Iraqi expansionism, signed its 1961 independence treaty with Britain under the title “Khalij Farsi.” Iraqi documents and maps from 1958 onward also continued to use “Persian Gulf.”

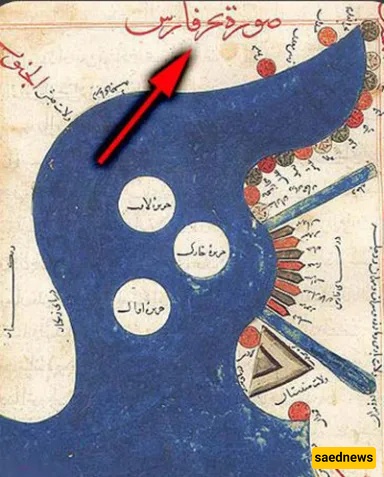

Countless documents affirm the gulf’s Persian name—so many that even hundreds of books could not encompass them. Colonial powers relied on this route to sell arms in exchange for oil and gas, posing threats to global peace. Changing its name without scientific or civilizational basis contradicts United Nations directives, as the standardized geographical name of the waterway between Iran and Arabia is the “Persian Gulf.”

Prominent references include:

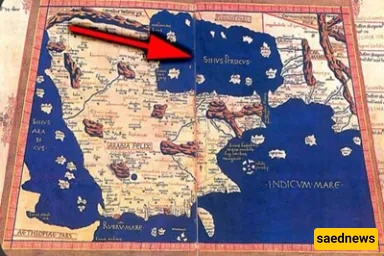

Ptolemy (150–87 AD), the father of geography

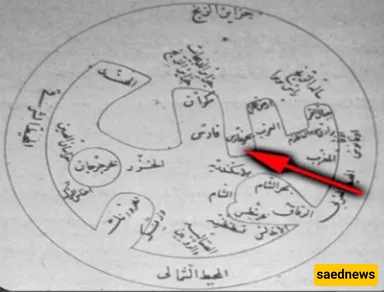

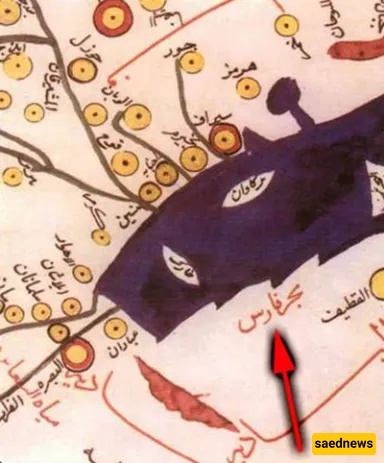

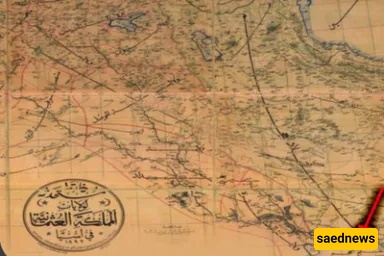

al‑Mas‘udi (900s AD), al‑Istakhri, Ibn Hawqal, al‑Idrisi, al‑Biruni

European cartographers from the 1500s to modern atlases (e.g., Petrus Bertius 1610; Oxford Atlas 2011)

National Geographic (1991)

United Nations (March 2011)

Encyclopaedia Britannica (1998)

And many more official and scholarly sources

In the early 1500s, Portugal’s naval forces under Afonso de Albuquerque seized Qeshm, Hormuz, and Gameroon (modern Bandar Abbas). Instead of military resistance, Shah Ismail I of the Safavid Empire opted for collaboration, inadvertently strengthening Portuguese footholds across the region.

Portuguese domination lasted 116 years until, by treaty with Britain, the East India Company aided Iran in reclaiming the gulf and Strait of Hormuz. On April 21, 1622, Shah Abbas I’s forces—led by Imam Qoli Khan, builder of Isfahan’s Si‑o‑Se Pol bridge—successfully captured Hormuz, expelling the Portuguese and cementing Safavid Iran’s status as a 16th‑century great power. Gameroon was renamed Bandar Abbas in honor of the shah’s victory.

To honor this legacy, Iran designated Ordibehesht 10 (May 1) as National Persian Gulf Day. Established by the Supreme Cultural Revolution Council in 2005 and registered in 2010 by the Cultural Heritage Organization, it commemorates the expulsion of foreign occupiers and the preservation of the gulf’s cultural heritage.

The Persian Gulf hosts numerous islands—some minor, others of major strategic importance. Most key islands belong to Iran, including Qeshm, Bahrain, Kish, Kharg, Abu Musa, Greater Tunb, Lesser Tunb, and Lavan.