SAEDNEWS: The Tas (also written as Tās) is a percussion instrument that closely resembles the Kus, Timpani, or Tumbal. Belonging to the family of drums, it holds an important place in traditional music. In this article, we’ll explore the origins and features of the Tas — stay with us to the end!

The Tās is a large percussion instrument, belonging to the same family as kettledrums such as the Kūs. It closely resembles the Kūs, timpani, or tombal and is especially common in Iran’s Kurdistan province. The Tās, or what Europeans call the timpani, consists of two metal bowls covered with animal skin, played with two thick leather beaters. This instrument is considered one of the ancient percussion instruments.

There are two main types: one martial form, consisting of a single bowl covered with skin, and another metal form, made in different sizes without a skin covering. In some rural areas, the Tās is played alongside instruments such as the dozaleh and sorna, although its use is not widespread. Traditionally, it is made from hollowed wood covered with skin and played with sticks, producing a sharp and dry sound. Sometimes, its bowl is made from metal containers. The use of the Tās is largely limited to ritual ceremonies in Kurdistan’s khāneqāhs (Sufi lodges), where it is usually accompanied by the daf.

The complementary instrument to the Tās is generally the daf or dotabla. In khāneqāhs, it is used during zikr (chanting rituals) and moments of collective standing, though occasionally it is played alongside the dozaleh and dohol. The main melodic patterns of the Tās include: Heirān, Giryān, Fattāh Pāshāyi, Lebelān, Zangī-Zangī, Seh Jār, and Shelān.

The word Tās originates from Middle Persian (Pahlavi), where it appears as tās or tāseh. In the rock reliefs of Taq-e Bostan, dating to the Sassanian period, a king on horseback is depicted with three rows of musicians behind him. In the top row, two musicians are playing percussion instruments, one of which seems to be the Tās, while the other plays a double-headed drum. The term “Tās” (and its variants) is frequently mentioned in early Persian music treatises. For instance, Marāghi in Maqāṣid al-Alḥān refers to this instrument in two different chapters.

In Persian poetry, the Tās also appears under names such as kās, kāseh, or kūs. Examples include:

“The kettledrum of his turn shall no longer be struck / Until he sleeps in comfort, with less burden on his heart.”

“The bronze kettledrum thundered aloud / Casting fear into the listener’s soul.”

Based on literary and folkloric sources, the Tās was historically a military and martial instrument. In Kurdish folktales, such as the story of Sharif Hamavand, the tahpaleh (Tās) is frequently mentioned. Its sound carried across valleys and villages, often used to signal events.

The body of the Tās is usually made from copper or brass, and occasionally from clay or wood, with rare examples in bronze. For copper Tās, ordinary household bowls were often repurposed, whereas brass bodies were custom-made by casting. Sometimes, a ball was placed inside the bowl to amplify resonance.

Size relation: Larger bowls produce deeper sounds, while smaller ones yield higher-pitched tones.

Air hole: Some bowls feature an opening at the bottom to regulate airflow.

Skin attachment: Animal skin is stretched across the opening and fastened with ropes or hooks. Occasionally, skins from different animals are used on paired drums—for example, wolf skin on the right-hand bowl and goat or sheep skin on the left—to create tonal contrast.

Traditionally, the Tās was played with two folded leather straps as beaters, but today rubber or wooden sticks are more common. In Kurdish, these beaters are called duwāl.

The diameter of a single Tās ranges between 22.5–48 cm, with a depth of about 30 cm. Paired Tās (do-tahpaleh) consist of a smaller bowl (jarrah, 16–17 cm) and a larger one (tuvār, 18–22 cm), both around 10–15 cm deep. The tuvār (left) produces the deep kut sound, while the jarrah (right) gives the sharp zaram sound.

The Tās can be played:

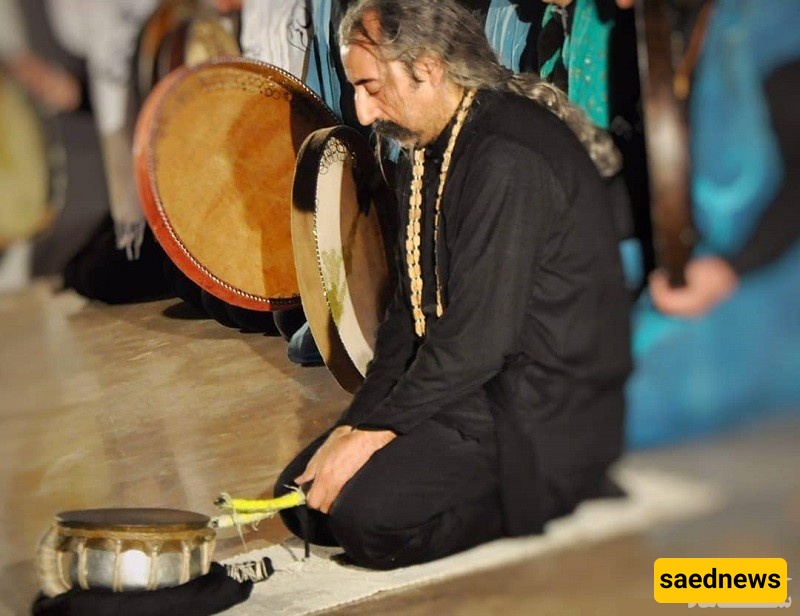

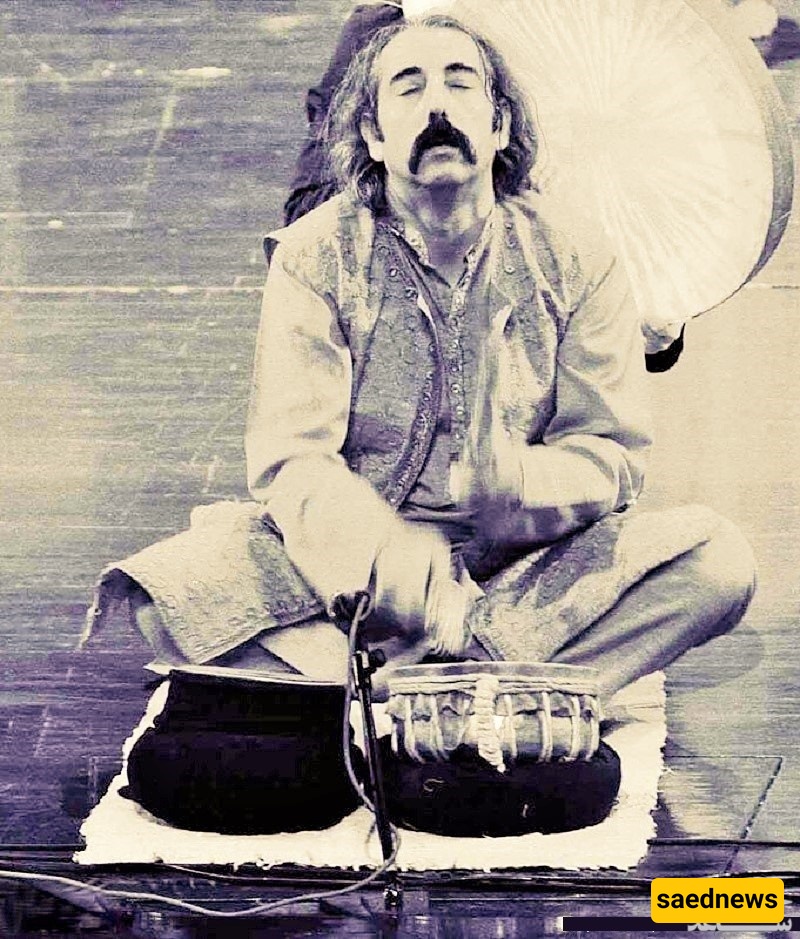

Seated – resting on the ground or the player’s lap.

Standing – placed on a tripod.

Mounted – strapped onto a horse’s saddle, especially for double Tās in military or tribal processions.

Execution techniques are relatively simple, though variations arise when using paired or triple sets. Strong beats are typically played with the right hand, lighter beats with the left.

The Tās often provides a march-like, tribal rhythm, clear and powerful enough to be heard from a distance, which is why it is sometimes called the martial instrument of nomads. In Persian military poetry, frequent references are made to its sound. The instrument is still taught and played in Iran, passed down through generations like a preserved cultural heritage.

The survival of the Tās may be attributed to its ritual and mystical functions. In the Qāderī order of dervishes, it is played alongside the daf and shamshal (flute) during zikr ceremonies. Its role is to reinforce the rhythm of the daf, create excitement, and intensify the spiritual and heroic atmosphere. In khāneqāhs, it is even called the “strength of the daf” (qūwat-e daf).

Historically, the Tās was also used for:

Messaging – to announce news, peace agreements, or even to disgrace someone.

War and migration – played on horseback during battles and tribal processions.

Religious and seasonal events – such as Ramadan dawn rituals, or during natural disasters like floods, earthquakes, and eclipses.

One of the most famous known players of the Tās is Amjad Ebrahimi. However, most masters of the instrument are Sufi dervishes, who generally avoid public recognition. Visitors to Kurdistan who attend a khāneqāh ceremony can directly witness the artistry and cultural significance of the Tās, an experience that reveals a unique dimension of Iran’s intangible heritage.