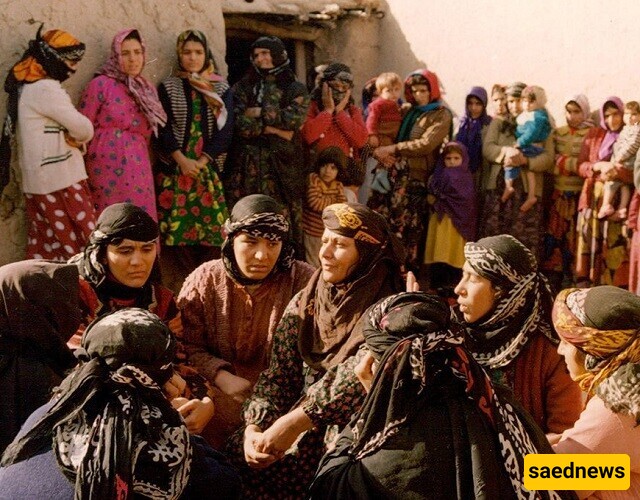

Saed News: "Khoon-Bas" is a form of tribal blood compensation used to resolve personal disputes and clan wars. Although its practice has significantly declined compared to the past, recent remarks by a judicial official in Khuzestan about nationally registering this tradition have sparked reactions from women and widely engaged public opinion.

According to the Society Service of Saeed News, quoting ISNA, the blood-settlement (Khoon-Bas) tradition is essentially a practice where, following a murder-related conflict between two tribes, women from the perpetrator's tribe are married off to men from the victim's tribe. The woman involved in this process is referred to as a "Fasila." The reason this custom is called "Khoon-Bas" (blood-settlement) is that, according to some, it prevents further bloodshed and retaliation by turning the two tribes into relatives through marriage. However, the main issue with this tradition is the formation of marriages that do not necessarily involve mutual consent, sometimes leading to forced marriages.

Some claim that the practice of women being offered in blood-settlement is nearly obsolete. Finding women who have personally experienced this is extremely difficult, and most individuals who have been in contact with these women say they are either unwilling to be interviewed or completely refuse to speak on the matter. Some believe these women fear cameras and microphones, while others suggest they are concerned for their safety. Efforts to locate these individuals have resulted in uncovering accounts from as far back as 70 years ago, as well as some more recent experiences, indicating that the practice has not entirely disappeared.

A woman from Andimeshk recounts three cases of blood-settlement brides among her acquaintances from 20 to 30 years ago. The first woman initially endured abuse and physical violence from her husband but now has five grandchildren and appears to have a good relationship with her spouse. However, the other two faced tragic fates. One of them, after giving birth to three children, suffered continuous beatings and abuse from her husband, eventually divorcing him. She later remarried and moved to a remote village, losing all contact with her children. The third woman, unable to conceive after three years of marriage and enduring ongoing mistreatment from her husband, set herself on fire in her home.

This source explains that historical accounts suggest happiness in such marriages was rare unless the husband genuinely cared for his wife and did not wish to harm her. However, she believes that in Khuzestan, this practice has significantly declined, as women today are less willing to submit to forced marriages, and economic conditions have changed, making financial considerations more significant than tribal customs. She also notes that many women who were once blood-settlement brides but still live with their husbands refuse to speak out, fearing the potential destruction of their family lives.

Another woman from Ilam shares two cases of blood-settlement marriages from approximately 70 and 30 years ago. In the first case, a woman and her two cousins were married off to men from the victim's family to end a blood feud. However, she was never allowed to see her mother again and, despite having seven sons and four daughters, was always viewed as an outsider and an enemy. Even her children were ostracized by the tribe, deprived of good food in childhood, and later in life, many of them struggled with addiction and financial ruin.

The second case involved a 15-year-old girl who was forced to become the third wife of a 60-year-old man to settle a tribal dispute. His first two wives treated her like a servant. She, too, stated that blood-settlement brides are often too afraid to speak to the media.

A woman from Kermanshah mentions that in this province, the custom of Khoon-Solh (blood-peace) has replaced Khoon-Bas. In cases of tribal or intentional murders, the perpetrator’s family visits the victim’s family carrying a shroud and a knife, declaring, "Either kill us or forgive us." This often results in forgiveness and the cessation of violence.

In Baluchistan, however, a man explains that if two major tribes engage in a deadly conflict, a woman from the perpetrator’s family may be married off to a man from the victim’s family, or, alternatively, one of the tribes may retaliate by killing a member of the other. If the conflict is to be peacefully resolved, a tribal elder mediates, and sometimes two marriages take place, uniting a boy and a girl from each side. However, in Baluchistan, it is emphasized that the bride’s consent is crucial, and generally, marriages occur with mutual agreement, unlike in some other regions.

Atieh Brouyeh, director of the Reyhaneh Women’s NGO in Ahvaz, offers a different perspective. She states that Khoon-Bas has primarily been practiced in five provinces: Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, parts of Fars, Kurdistan, Khuzestan, and Kermanshah. The girls subjected to this practice are victims of the actions of the men in their tribes, often enduring severe psychological distress and humiliation. Essentially, they become hostages or bargaining chips for peace, and the victim’s family takes out their vengeance on the bride. These women are often denied traditional wedding ceremonies and are simply transferred from their father’s home to their husband’s.

She acknowledges that Khoon-Bas has largely faded in Khuzestan, not due to external legal intervention, but because the tribal communities themselves have come to recognize its injustice. However, she does not claim that the practice has been entirely eradicated. Due to the lack of reliable statistics, it is unclear how often it still occurs, particularly in remote villages.

A recent controversy arose when a judicial official in Khuzestan proposed that Khoon-Bas be officially recognized as a national tradition. This proposal, made on July 21st, sparked outrage among civil activists. In response, a campaign was launched using the hashtags #IAmNotAFasila and #IAmNotABloodSettlementBride, as activists feared that recognizing the practice as a national tradition could legitimize it rather than condemn it.

A formal petition was submitted to the Judiciary Chief, outlining how Khoon-Bas contradicts constitutional principles regarding marital consent. On August 16th, the judiciary confirmed that the proposal for Khoon-Bas recognition was canceled. However, activists criticized the Cultural Heritage Organization for even considering such requests, questioning whether persistent reapplications might eventually lead to approval.

Brouyeh highlights the significance of this campaign, noting that it marks the first time Arab women in Iran have collectively protested a social issue. While previous instances of honor killings and domestic violence in Khuzestan were either ignored or dealt with privately, this movement gained national attention, bridging the gap between ethnic minority women and mainstream feminist movements in Iran. The extensive use of social media amplified their voices in a way that was previously impossible.

Legal expert Fatemeh Babakhani states that there is no specific legal protection for blood-settlement brides in Iran, and the matter is often left to tribal authority. However, international conventions, such as CEDAW (Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women), explicitly prohibit forced marriages based on tradition. In Iran’s Civil Code, mutual consent is a requirement for a valid marriage, meaning Khoon-Bas marriages technically violate Iranian law.

Babakhani recounts a recent case in Urmia, where two young blood-settlement brides self-immolated due to severe mistreatment. In one case, the bride was expelled from her husband’s home but was also rejected by her own family, ultimately leading to her suicide. Disturbingly, her tribe praised her parents for "preserving their honor" by not taking her back.

She also notes that children from blood-settlement marriages often face severe discrimination, denied inheritance rights and ostracized within the tribe. Women in such marriages typically have no right to divorce, inheritance, or even education.

While Khoon-Bas has significantly declined, particularly in Khuzestan, it remains a grave human rights concern in certain regions. The fight against its recognition as a "cultural tradition" highlights the growing voice of women’s rights activists in Iran, but many challenges remain in ensuring legal protection for affected women and children.