A Qajar garden turned hotel in Mehriz — water from an old qanat, 2,500 citrus trees, a 400-car park and a hotel that sleeps like the past.

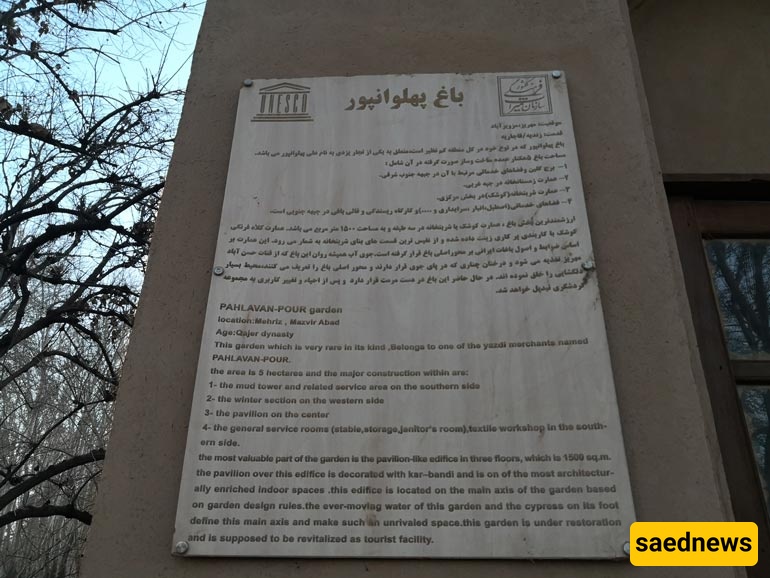

One of Yazd’s most arresting sights is Bagh-e Pahlavanpour in Mehriz — commonly called Bagh-e Pahlavan — a garden whose story begins with the marriage of two families whose neighbouring gardens were joined. The result is the lush, beloved Bagh-e Pahlavan.

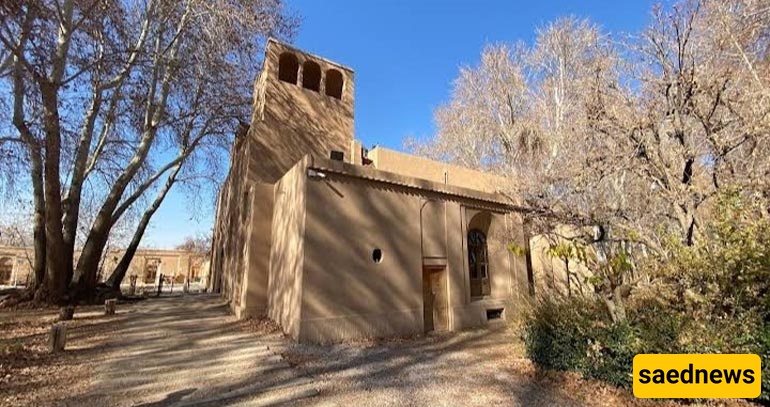

The garden’s distinctive architecture draws visitors in; in this piece for Alibaba Travel Magazine I share the mood and impressions from my visit to Mehriz.

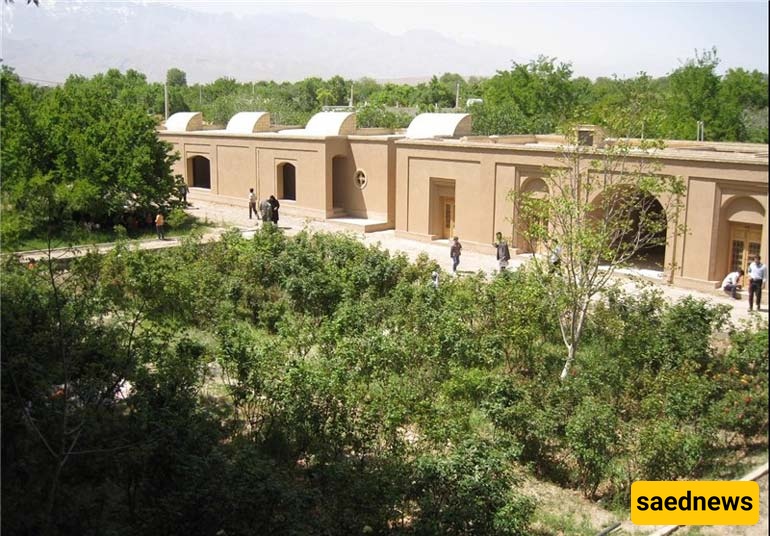

Bagh-e Pahlavanpour is in Yazd province, in Mehriz county, on Motahari Street. It is one of Yazd’s noteworthy attractions, showing off Mehriz with green trees and fine architecture.

The garden’s opening hours run from 08:00 to 18:30, and it is closed on certain religious or national mourning days such as the 18th of Safar, Tasua and Ashura, the anniversary of Imam Khomeini’s death, the martyrdom of Imam Jafar al-Sadiq and the martyrdom of Imam Ali.

Bagh-e Pahlavan dates to the Qajar era. Originally the property belonged to a man named Hasan Molla Reza; later his son-in-law, Mr. Ali Pahlavanpour — a prominent merchant from Yazd — became the owner and the garden took his name.

A local story tells that two neighbouring gardens once stood side by side, separated by an earthen wall. When Hasan Molla Reza’s daughter married Ali Pahlavanpour’s son, the families removed the dividing wall and the two plots became the single Bagh-e Ali Pahlavanpour.

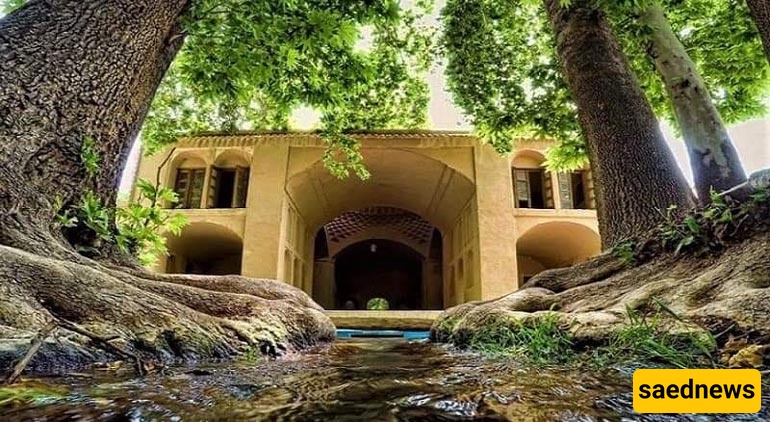

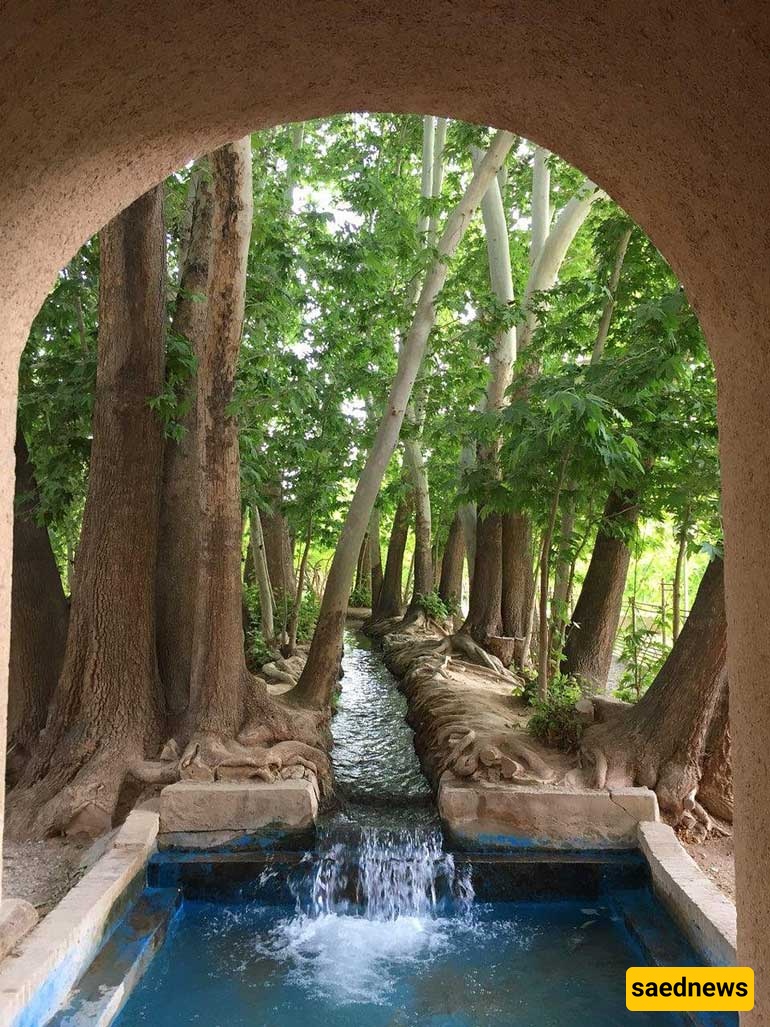

On arrival the first striking sound is the running water in the garden’s main stream. The Hasan-abad qanat supplies the water that flows through Bagh-e Pahlavan; notably, the garden is the qanat’s final stretch.

The garden was named after the groom — Ali Pahlavanpour — when he married Hasan Molla Reza’s daughter and the combined estate became known as Bagh-e Ali Pahlavanpour.

One notable feature is the garden’s architectural style, which blends traditional Iranian forms with more modern garden-planning elements. Although the garden is not ancient in every part, its design echoes older Qajar motifs seen elsewhere in Yazd.

You can spot historic cues throughout the site that recall Qajar culture — especially the kooshk (pavilion) style. The main complex mixes a kooshk layout with a central courtyard, producing an appealing fusion of residence and garden.

Important buildings include the kooshk (main pavilion), the winter house, the sharbat-khaneh (refreshment pavilion), the kitchen, a historic bath and the steward’s house. As noted, the garden’s flowing qanat is a central organizing feature.

Water in Bagh-e Pahlavan also moves along a second axis, so the garden is arranged around two principal water courses. Trees lining these channels create a regular, pleasing geometry.

Bagh-e Pahlavan is not a place for a very short visit; it contains many parts that invite lingering. On entry, the sound of water stands out — the qanat arrives into the garden, bringing life and greenery. Without that water, the site would be little more than buildings and dry land.

Close your eyes and you hear other small wonders: wind threading through leaves, birds that have made the garden their home for generations. The qanat and breezes together create a cool microclimate that makes the garden feel refreshingly comfortable even when the sun is hot.

At the entrance area are a stable, a tower and a hayloft (kahkan/kahedan) — built in the Qajar period but carrying decorative elements that were added earlier, during the Zand era.

The kooshk — also called the sharbat-khaneh — is the garden’s grandest building and dates from the Qajar era. The two-and-a-half-storey pavilion sits on the main axis. Inside you find halls, a Kolaah-Farangi (a delicate pavilion room), alcoves and the central pond-room (hovzkhaneh).

The Kolaah-Farangi is among the most exquisite parts of the kooshk; its ornamentation rewards long, patient observation.

A branch of the Hasan-abad qanat runs through the kooshk itself, so water literally passes beneath the building. Standing with your back to the kooshk you can see the two water channels that frame the garden; these streams feed the old trees and tie the whole composition together.

Workshops for carpet weaving and spinning, plus storerooms, date from the Qajar period. These buildings reveal that the garden once supported active craft and production; to the north you can still see quarters used by workers and attendants.

The winter house is a later, Pahlavi-era single-storey building with living rooms, storage and a kitchen — designed so people could live there comfortably in the cold season.

The ethnography museum was initially set up in a historic bath (the Estehri Bath) and later moved into Bagh-e Pahlavan. Today the collection holds more than 4,000 items: tools associated with local trades, traditional clothing, old inscriptions and cooking vessels — a broad record of regional life.

Excavations have revealed an array of service spaces — kitchen, storerooms and baths — that sit beside the kooshk and have been restored to view.

Like many historic properties in Iran, Bagh-e Pahlavan now contains a hotel complex. The hotel opened in 2009 (1388) and offers 13 rooms ranging from single to quadruple suites. A noteworthy facility is the hotel’s 400-car parking area with garden views.

In the garden courtyard guests have access to leisure facilities such as a football pitch, beach-volleyball court, table football and table tennis. The suites are styled to evoke life in the Qajar era.

From Yazd city centre to Bagh-e Pahlavan in Mehriz is 47 kilometres and about a 28-minute drive. The nearest major airport is Shahid Sadoughi International; the airport is about 48.6 kilometres away (roughly 44 minutes in normal traffic). The rail station lies about 44 kilometres away (approximately 37 minutes).

The recommended route from Tehran follows Tehran-Qom highway, continues on the Persian Gulf freeways and joins the Nain corridor via Kashan, then on to Yazd-Mehriz roads. The full drive described in the article totals about 667 kilometres and was estimated at roughly 7 hours 39 minutes of driving time.

Like many Yazd attractions, the garden is busiest in certain months. The article advises spring or autumn for visiting: spring for fresh budding leaves, and late-September through early-January for cool autumn weather and pleasant walks.

Because the garden includes a hotel, visitor facilities are substantial: a 400-vehicle parking lot, a restaurant, restrooms and play areas.

If you have time beyond the garden, Mehriz and nearby Yazd offer many sights to complete a visit.

– Park-e Sarv (Sarv Park) — a park built around an ancient cypress (near the garden, about 3.9 km / ~8 minutes).

– Hasan-abad spring and adjacent mill — the Hasan-abad qanat originates in the Modvar hills and flows through the kooshk; its waters are unusually low in dissolved minerals and regarded as high quality. (The qanat’s mapped location is not recorded in Google Maps; it sits close to the garden.)

– Bagh-e Khoshnevis (Khoshnevis Garden) — a nearby converted guesthouse and garden with a similar history; it stands about 1.5 km from Bagh-e Pahlavan and can be reached on foot or by a short drive.

– West-Albiz historic area — an archaeological zone with circular courtyards and defensive earthworks; roughly 8 km from Bagh-e Pahlavan (about 16 minutes by car).

If you plan to visit, remember these tips drawn from the site:

Because a hotel operates inside the garden you do not need camping equipment; however camping is possible if you prefer.

Visiting is allowed between 08:00 and 18:30 — plan your visit inside these hours.

The garden is closed on certain religious observances (e.g., 28 Safar, Tasua/Ashura, martyrdom anniversaries, and the day of Imam Khomeini’s passing) — check dates before travelling.

The kooshk and the Kolaah-Farangi are among the most beautiful spots — sit under their shade for a while.

Tickets are required for entry.

If you drive, the hotel parking accommodates up to 400 cars.

Bagh-e Pahlavanpour in Mehriz is a Qajar garden that today invites visitors to wander and rest. Beyond its architecture and buildings, the garden offers nearby attractions and a hotel experience that re-imagines Qajar life. Don’t miss the kooshk, the qanat and the garden’s ethnography collection — and consider booking your trip to Yazd to include at least a night inside this living piece of history.

Item | Detail |

|---|---|

Location | Mehriz, Yazd province — Motahari Street |

Opening hours | 08:00 – 18:30 |

Days closed (examples) | 18 Safar, Tasua, Ashura, death of Imam Khomeini, martyrdoms of Imam Ali & Imam Jafar al-Sadiq |

Garden era | Qajar period |

Hotel rooms | 13 rooms (single → quadruple) |

Ethnography collection | ~4,000 objects |

Parking capacity | ~400 vehicles |

Notable trees | Mature date palms and other tall trees lining two water axes |

Distance from Yazd |

|

Nearest airport | Shahid Sadoughi — |

Attraction | Approx. distance / time | Notes |

|---|---|---|

Park-e Sarv (Sarv Park) |

| Park around ancient cypress |

Bagh-e Khoshnevis |

| Converted garden guesthouse |

West-Albiz historic area |

| Archaeological zone, ancient defenses |

Markar Museum (Yazd) | — | Zoroastrian museum (recommended) |

From Yazd city centre |

| Driving time as given in article |

Tip | Short explanation |

|---|---|

Visit in spring or autumn | Best weather; spring shows fresh foliage, autumn is cool and pleasant. |

Check opening days | Garden opens 08:00–18:30 but closes on listed religious/mourning days. |

Buy an entry ticket | Entry requires a ticket — plan to purchase before entering. |

Use on-site parking if driving | Hotel parking holds ~400 cars; useful for travellers by car. |

Explore the kooshk and Kolaah-Farangi | These are the garden’s highlight interiors — allow time to sit and enjoy. |