SAEDNEWS: Siemens, headquartered in Munich, is Europe’s largest industrial manufacturer. Its main fields are industry, energy, healthcare, and urban infrastructure. This article examines how Siemens rose to play a key role in the communications revolution.

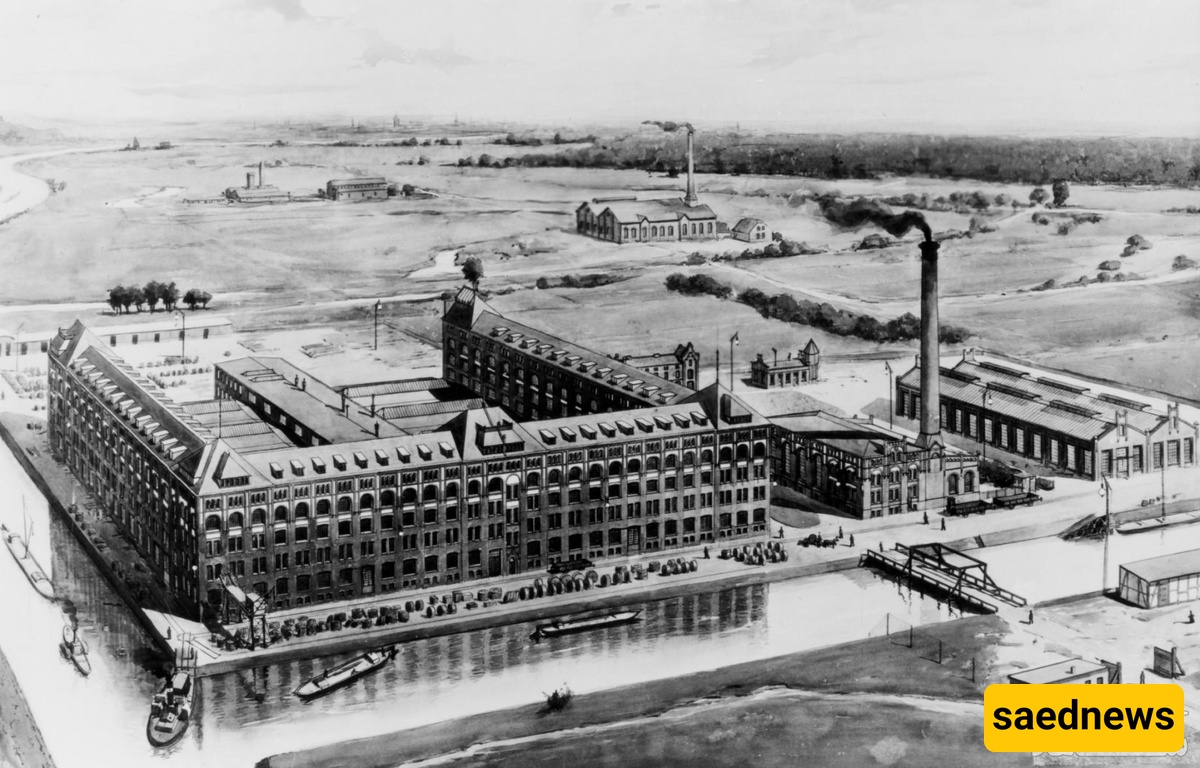

Today, Siemens operates in telecommunications and lighting equipment, household appliances, trains, power generation systems, automation and industrial controls, medical devices, and fire alarm systems. The company’s operations are divided into four main sectors: energy, industry, healthcare, and urban infrastructure. Siemens employs over 360,000 people across 190 countries, with its headquarters located in Munich, Germany. But where did Siemens begin its journey?

The history of information exchange is as old as human civilization itself. However, with the advent of electricity in the 19th century, the speed and volume of information transfer underwent a revolutionary change, transforming communication technologies. To understand this transformation, one must look at the history of Prussia and the Siemens family. While Prussia was on the path to industrialization and the number of industrial investors was growing, the Siemens brothers’ companies enjoyed a unique position in communication technology and electrical equipment production.

After the Napoleonic Wars ended in 1815, the Kingdom of Prussia, centered in Berlin, was industrially underdeveloped. By the 1860s, Prussia had achieved significant industrial growth, and its economy flourished. Before the 1840s, industrial investment was limited and unstable. A combination of small markets and limited government support made private industrial investment risky, so investors preferred public works that met national needs. Prussia offered limited support for industrial projects but encouraged private companies to invest.

When industrialization began in Prussia and other German states in the 1830s, a strong administrative system was already in place. Efficient bureaucratic structures influenced all aspects of society, facilitating economic, social, and political modernization. These structures extended to newly established factories, where government officials often acted as investors and experts in mining, railways, and other industries were employed. Engineers concentrated in technical, administrative, and military units played a pioneering role in industrial education and scientific societies.

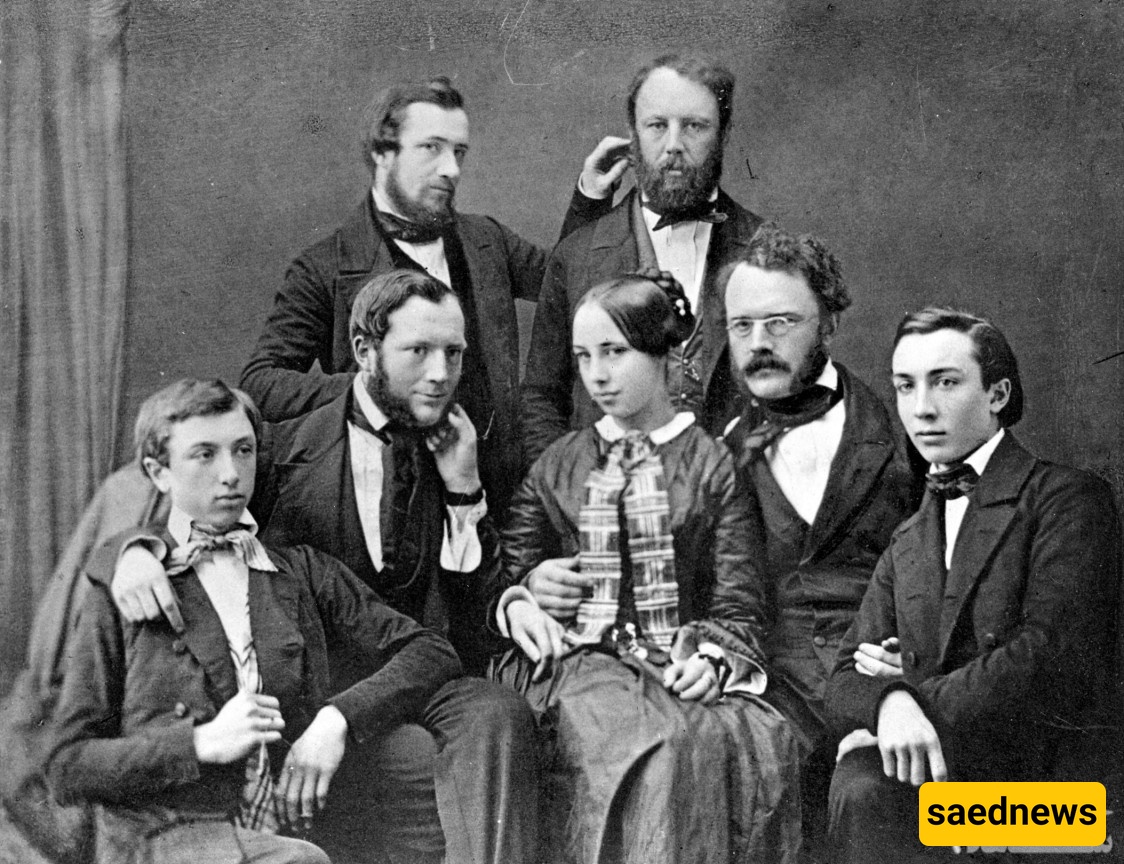

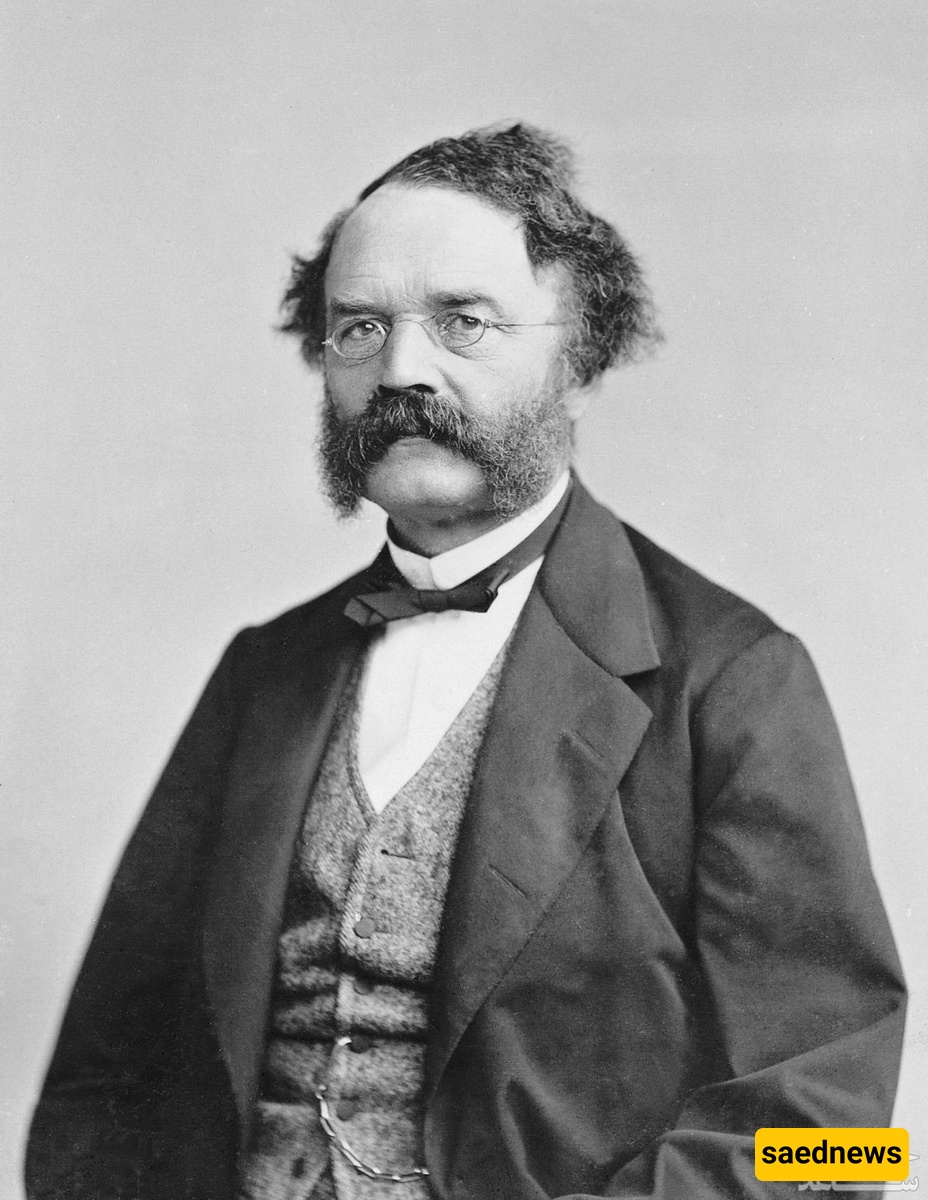

The Siemens brothers—Werner, William, Karl, and Friedrich—invested in various industries including electrical, mechanical, telegraphy, metallurgy, glass, and mining. They were descendants of a farming family from northern Germany, with Christian Ferdinand Siemens as their father. Werner Siemens founded the first company with a mechanical collaborator, Johann Georg Halske, which quickly expanded internationally, opening branches in St. Petersburg and London by the early 1850s. The company produced and installed telegraph cables and electrical equipment, employing growing numbers of staff in Berlin and beyond.

The Siemens brothers maintained close collaboration across their businesses, integrating engineers and specialists from governmental technical services, bringing bureaucratic methods and operational principles to their growing company. Werner Siemens later wrote: “From my youth, I aspired to create a business on a global scale… not only for myself but for my descendants, and to provide opportunities for my family to achieve a better standard of living.”

Werner’s education, military career, and scientific studies in mathematics, chemistry, and physics shaped his economic and industrial strategies. Both he and William leveraged their academic and professional networks, which facilitated Siemens’ rapid international success in its first decades.

Before the electrical telegraph, Europe and the United States relied on optical telegraphs, mechanical signaling systems developed in the late 18th century by Claude Chappe in France. While faster than horseback messages, these systems were limited in capacity. In 1837, the electric telegraph was independently invented in England and the United States. In Prussia, telegraph workshops in Berlin led to the establishment of Siemens & Halske in 1847, funded in part by family loans.

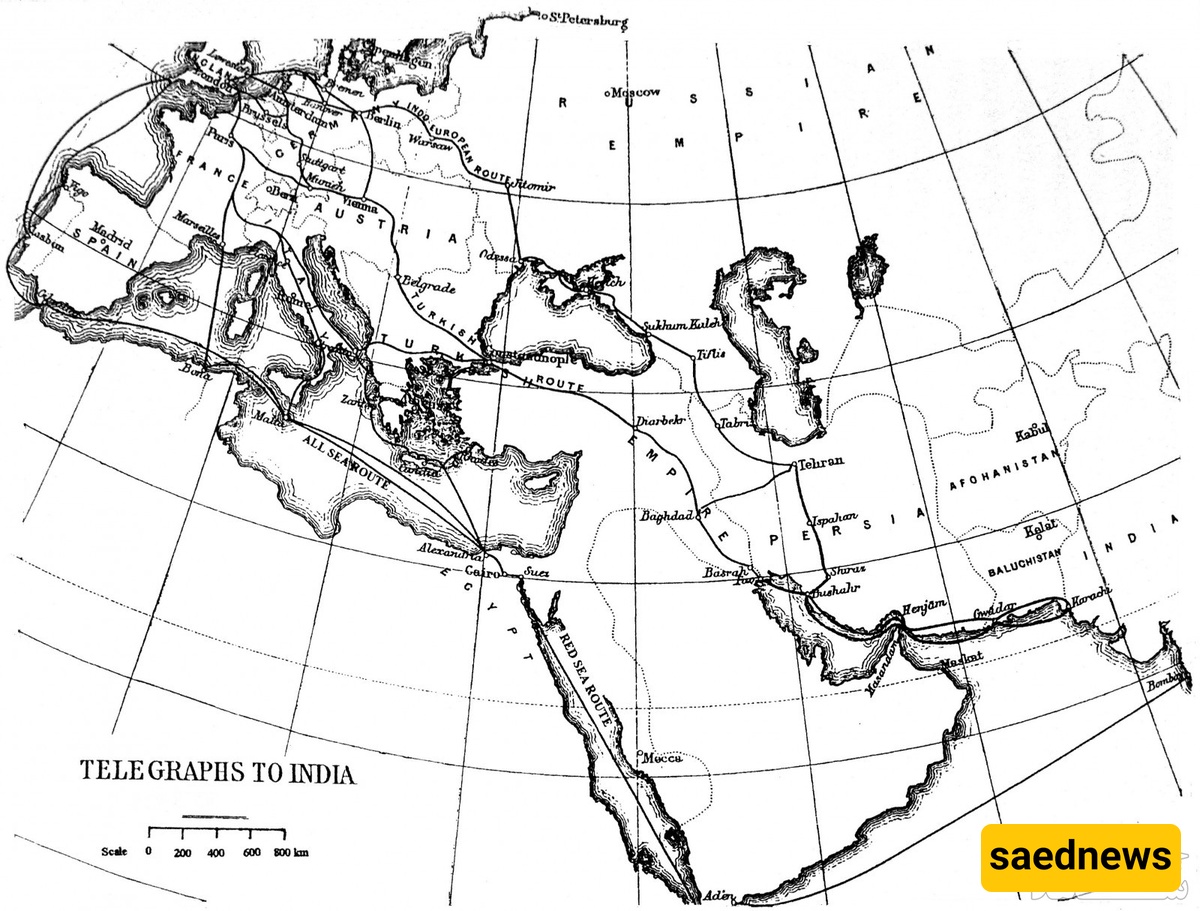

The Prussian government became a primary customer, commissioning projects to improve the telegraph system, including lines connecting Berlin to Frankfurt and Cologne. Siemens’ success in Prussia enabled expansion into Russia in 1852, establishing a major branch in St. Petersburg to manage telegraph networks, including strategic deployments during the Crimean War (1853–1856). Siemens subsequently extended telegraph lines across Finland, Poland, Ukraine, and the Black Sea region.

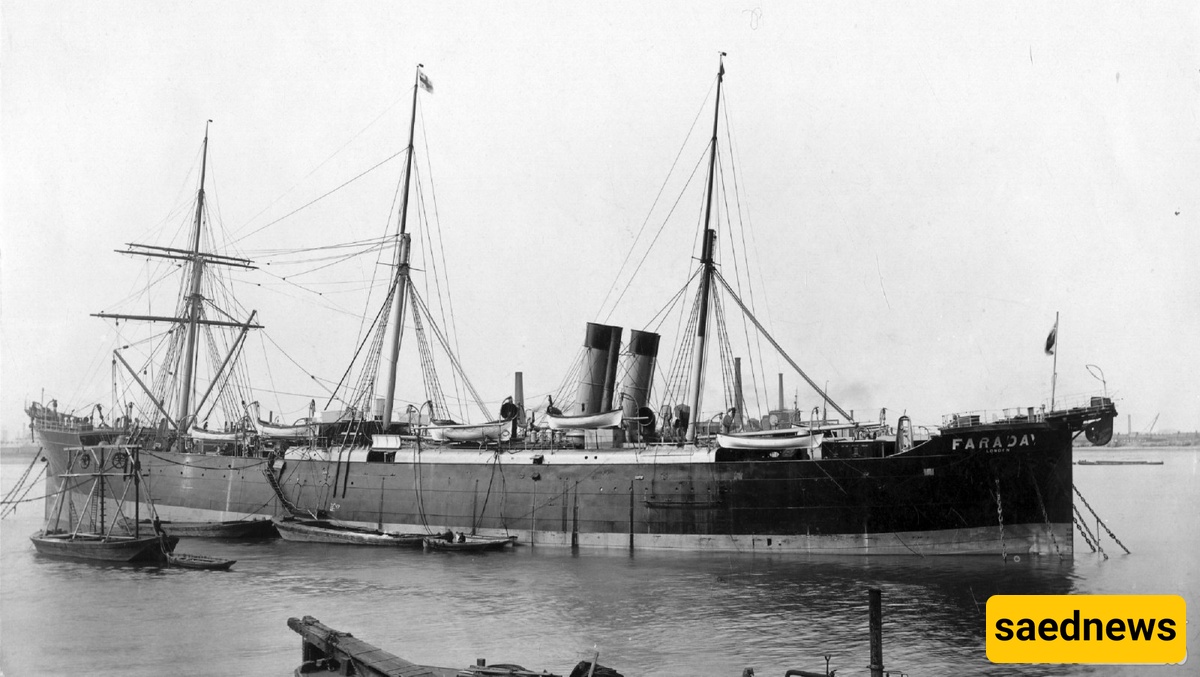

In the United Kingdom, Siemens established a branch in London in 1850, producing and installing telegraph and submarine cables, including for the growing British Empire. The company contributed to Mediterranean communications and, later, the first transatlantic cables between England, Ireland, and the United States in the 1870s. Siemens’ expertise also supported projects connecting Europe to India via landlines and submarine cables through the Persian Gulf, facilitating rapid, reliable telegraph communication.

Siemens’ expansion across Prussia, Russia, and Britain demonstrated the power of effective management, family networks, and applied innovation. Their telegraph networks had military, economic, and political significance, establishing the foundation for modern global communication. By integrating scientific research with practical applications, the Siemens brothers played a key role in shaping early information technology, industrial infrastructure, and global trade networks.

The company’s early efforts in telegraphy, submarine cable installation, and industrial production exemplify how technological innovation, strategic planning, and cross-border cooperation can create transformative global enterprises. Siemens’ story is not just about electrical engineering; it is about connecting continents, accelerating communication, and laying the groundwork for globalization.